All of 12 years old, Alyssa Elmore is on her way to becoming a renaissance child. A fan of Kelly Clarkson and the stars of “American Idol,” she’s big on horses, and wants to pursue animal studies and architecture. It’s a far cry from when she was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder, put on Ritalin and told to enroll in a special education class. When the school bus rolls through her Bremerton, Wash., neighborhood, she stays home. But Alyssa’s not skipping school. Fact is, she’s already there.

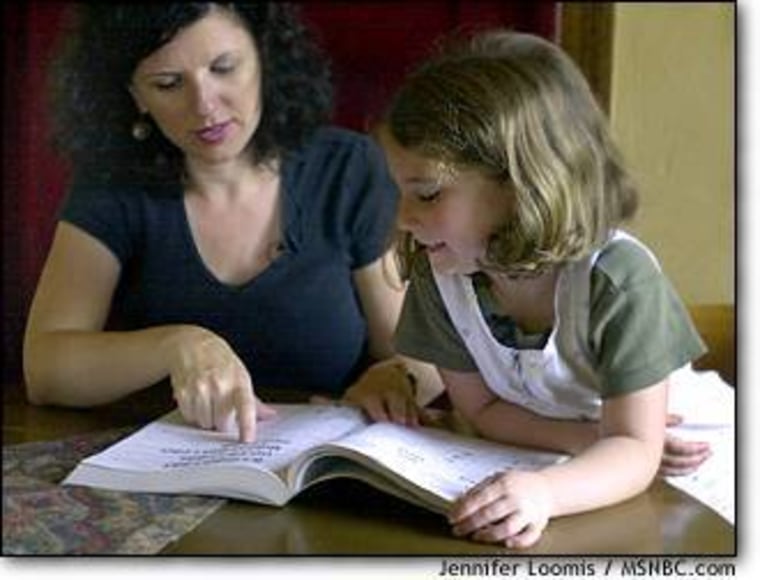

Like tens of thousands of other parents, Marti Elmore, Alyssa’s mother, began homeschooling Alyssa and her sister Aine, 7, out of frustration with the quality of education her children were getting in public schools. A stay-at-home mom and former PTA president, Elmore took action after Alyssa got the ADD diagnosis.

Changes made

“When Alyssa was in school, she thought, ‘What’s wrong with me?’” said Elmore. “She kept saying, ‘I’m stupid, I’m dumb.’ And I thought, “Oh gosh, we’ve got to get her out of this environment.’ We saw her esteem going downhill.”

After spending months working within the public school system to resolve Alyssa’s problems and unable to find a local, non-religious private school, Elmore and her husband, Rocky, pulled Alyssa out of formal classes altogether. The family joined a local network of homeschoolers and created their own curriculum.

Three years later, she’s off Ritalin and working above her grade level in many subjects. While in some ways she’s a typical 12-year-old — “She used to be into Britney Spears, but not so much anymore,” her mother says — in other ways she’s bloomed beyond her age.

“She’s doing volunteer work now, and she’s really into horses and dogs,” said Marti Elmore. “She wants to pursue animal science and business. She’s also really into architecture — sketching floor plans and designing a neighborhood that’s equestrian-friendly. She’s into filmmaking, too.”

‘Out in the world’

“Last year she went to Morocco,” Marti Elmore relates. “She helped put together a water filtration system with Berber children. We went into the Sahara, collecting rock and soil samples.”

This precocious polymath is brought to you, at least in part, by home schooling, an approach to teaching and learning that’s gaining followers in the United States.

As the nation grapples with a fragile economy; a declining teacher-student ratio; rising concerns over school infrastructure and maintenance; the prospect of school violence; and fears that abide in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the numbers of home-schooled children are growing apparently based on a fact that educators and its adherents confirm: It works.

How quickly the practice is growing is anyone’s guess.

An August 2001 Census Bureau report on U.S. home-schooling trends estimated that perhaps as many as 2 million children are home-schooled. The home-schooling growth rate is an estimated 15 to 20 percent annual increase, a growth rate that’s caught the attention of politicians and school administrators.

The National Home Education Network, a Florida-based advocacy organization, reports that “because not all states count homeschoolers, and because homeschools in some states are indistinguishable from other private schools, there are no hard numbers.” The organization reports research estimates of from 1.5 to 2 million homeschoolers in the United States, representing 3 to 4 percent of the school-age population.

A trend to watch

In raw numbers, homeschooling is no threat to traditional education.

More than 50 million students attend some 86,000 public schools in the United States — a number that’s increased about 10 percent since 1990, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers, which gave U.S. schools a D minus in its 2001 Infrastructure Report Card.

But as school budgets shrink and public-school enrollments rise (A 2002 American Association of School Administrators study found that 44 states had education funds cut or holding steady, as the number of public-school students grew), home schooling has proved to be a meaningful alternative.

In an August 2001 report, the U.S. Census Bureau said homeschooling is emerging “as an important national phenomenon.”

And home schooling has more than held its own where it counts: in the learning. In a 1998 study, the Education Policy Analysis Archives found that achievement levels of homeschoolers “are exceptional.” In that study, the Archives, a peer-reviewed scholarly electronic journal, found that ”[b]y the time home school students are in 8th grade, they are four years ahead of their public/private school counterparts.”

Diverse as America itself

The Elmores’ situation mirrors the experience of a growing number of American families searching for creative ways to educate their children. For Marti Elmore, homeschooling “is more enriching than what [Alyssa’s] alternative was.”

Census statistics show that home schooling has most dramatically increased in suburbs and rural areas of the West and Midwest, among middle-class families with higher levels of education and one parent who stays at home. Most home-schooling parents are white, but a growing number of black and Hispanic families are also beginning the practice.

Susie Marshall is a teacher in charge of testing and accountability for homeschool families in the Riverview School District, serving the towns of Carnation and Duvall, Wash. Marshall has a special relationship with homeschooling; she taught one of her daughters from home, and is now an advocate for homeschool families in the district, helping navigate the differences between homeschooling and traditional education.

“When I home-schooled [daughter] Tia in middle school, they wouldn’t let her go into honors English in high school because she didn’t have a recommendation from middle school. It changed with the law. The law gives freedom and encouragement to help home-schooling families.”

“We see parents as the children’s primary educator,” Marshall said. “The parents work with their kids three-and-a-half, four days a week on their education. Then the parents take a break and send them to us one day a week.”

Between learning and a fun place

“The premise behind all this is that learning has got to be fun,” she said. “We’ve got to find ways to make it exciting.”

The never-ending challenge for home school educators, however, is finding a way to make learning fun, but not too much fun. Home-schooled students are going to classes in the same place as their video games, their MP3 players, their Britney and Justin posters — all the diversions of their lives outside school.

Marshall said that distractions aside, at some point, education has to be its own reward. “For older kids, there’s got to be a motivation,” she said. “It’s harder than just showing up at seven-thirty every morning at the high school.”

Taint of the wacko

Despite growing numbers of educators and lawmakers who attest to home-schooling benefits, there’s still the taint of the reclusive crackpot associated with the practice. Home schooling became a measurable trend when it was embraced by families swept up by the counterculture ethos of the 1960s and ’70s. In the ’80s, the movement was largely driven by the religious right and anti-government groups convinced that public schools had become morally and ideologically corrupt.

Things have changed. “Home schooling isn’t just being done by a bunch of people with guns in Idaho,” said Jane Ferrall, a former attorney who teaches her four children — ages 13, 11, 8 and 5 — at home in Darien, Conn. “It’s really becoming a mainstream thing.” said Ferrall, a leader for a local Girl Scout troop and a Sunday-school teacher busy making brownies the night a reporter calls.

Ferrall, starting her third year as a home educator, thinks her decision has been a good one.

“As states continue cutting their education budgets and live with the fact that the feds aren’t giving them any money, more middle-class people will look at home schooling,” she said. “It strikes me as being something that people being dissatisfied with education will consider as an option. Even teachers will say to me, ‘what a great idea!’ ”

The ‘S’ word

For Marshall, who is a teacher, the best of both worlds is possible: the creative latitude of homeschooling with the didactic rigors of public-school education. That’s a balance she tries to help other parents achieve.

“A lot of involved mainstream parents see what these kids are doing,” she said. “They see home schooling as something they can do for a year or two to help a child get more time to mature, to give them more skills in a certain area, and to build family closeness.”

For adherents, home-schooling doesn’t replace a life in the world. “There’s an image of us sitting at the kitchen table all day with no access to other kids,” Marti Elmore said. “I’m sure there’s people out there who do that, but home-schoolers get out in the world. They’re not stuck in a building for six hours.”

For some critics of home schooling, the big problem is kids failing to gain socialization. They argue that home-schooled children are closeted away, sequestered from the world, prevented from developing the social skills needed to function in society.

“Unless you’re going to keep your children in a bubble for the rest of their lives, you have to expose them to a world that isn’t always sweet and nurturing,” said Dr. Ted Feinberg, assistant executive director for the National Association of School Psychologists.

Feinberg is also concerned that home schooling blurs the boundaries between parent and child, preventing the child’s natural pulling away from the parent during adolescence.

“Education has to be looked on in a broader context,” he told MSNBC.com. “If we see it solely as the acquisition of academic skills, that’s a narrow view of what an educated person or child needs to be. Certainly the range and the variability of that experience is more limited from my vantage point with home-schooled kids than with those who have an opportunity to attend public or private schools. Social learning is an integral bulding block for all of us in terms of dealing with the world that we inhabit.”

‘A lot of meanness’

But some home-schooling parents argue that, whatever the risks of a cloying child, the pressures of sex, drugs, bullying, and worse in schools far outweigh these concerns. “There’s a lot of meanness,” Marshall said. “Middle school’s a hard transition and a lot of us have memories of mean kids during that time.”

For the McFaddens, an Army family stationed in Fayetteville, N.C., home schooling is a viable option because of the potential for violence in public schools.

For Mark and Susan McFadden, the decision to educate their three children at home came after daughter Kaitlin was repeatedly bullied at school by a boy in her second-grade class who made sexual advances toward her and ultimately threatened to kill her. Despite attempts by school officials to intervene, the harassment continued and the McFaddens finally pulled Kaitlin out of school.

“We were just completely frustrated. We were concerned for her safety,” said Susan McFadden.

Now, Kaitlin’s work is much improved. “She performs very well on her standardized tests and she makes friends outside the home, so socialization isn’t an issue,” Susan McFadden told MSNBC.com.

For Marshall, the McFaddens and surely for others, the litany of recent deadly school incidents is a major concern. A study on lethal school violence by Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study found that from 1992 to 2001, there were 13 multiple-victim shootings in rural and suburban U.S. schools. The violence, which peaked in April 1999 with 15 people slain in the Columbine High School shooting in Colorado, left 44 people dead, 88 injured, and nine teenage gunmen — student assailants — imprisoned.

Battling boredom

For the Messerlys of Texas, another enemy was boredom. John Messerly, a computer science professor at the University of Texas in Austin, and his wife, Jane, a computer consultant, began teaching their son John and daughter Katie at home when the kids were in middle school. “Both of them just hated being bored in school,” said the elder John Messerly.

The results were promising: Both Katie and son John went on to win scholarships to Case Western Reserve University; both started college early — Katie at age 14, John at 15.

While pleased with the progress of his children academically, John Messerly related homeschooling’s good and bad aspects. “Katie has flourished completely,” he said of the gymnast daughter, now 19, who skydives and is an intern with Microsoft in Redmond, Wash. She’ll graduate from Case Western next year. (MSNBC is a Microsoft-NBC joint venture.)

Son John also achieved academically, graduating from Case Western with a degree in computer science, but his father recalled how a painfully shy young man never quite developed socially. “He’s never had a good friend in his life,” John Messerly said. “My wife wondered if it was because he never had the social experience he might have had in high school. He’s done a little better with some counseling. But he’s had some problems that could have to do with some of the choices we made with him.

John Messerly isn’t sure if the traditional school system — its tests and challenges, its proms and rituals — might have helped his son integrate socially. “It’s hard to know if homeschooling retarded him socially, but I think I would be forced to admit that it probably was a downside.”

Colleges, lawmakers take notice

Given the one-on-one attention that home-schooled children generally receive and the ability to customize curriculum, the testimonials of greater academic achievement after kids are withdrawn from public schools aren’t surprising. Homeschoolers make national headlines winning spelling and geography bees, and home-schooled students from the artist Andrew Wyeth to tennis superstars Venus and Serena Williams have made inroads in society at the highest levels.

A 2001 study by the U.S. Department of Education found that minority children educated at home fared better on reading and math scores than their counterparts in public schools.

And home-schooled students have used the yardstick of traditional education — the SAT test — to their own advantage.

In 2002, home-schooled students averaged 1,092 on the SAT, compared with the national average of 1,020, according to data by the Home School Legal Defense Association.

Understandably, legislators have taken notice. In July, Colorado Rep. Marilyn Musgrave introduced the Homeschool Non-Discrimination Act in Congress. Musgrave’s bill seeks to put home schooling on a more level footing with traditional schools. The measure would allow home-schooled students to be eligible for college scholarships, and sets equal treatment for the dissemination of home-schooled students’ records and those of students from traditional schools.

And perhaps just as understandably, top colleges have begun accepting record numbers of home-schooled students.

At Harvard University, the home-educated are treated like any other applicants during the admissions process. They’re required to provide SAT scores, letters of recommendation, information on extracurricular activities, a personal essay, and grades from any courses they’ve taken.

“Our job is just to get great students wherever they are, whether they’re on a mountaintop in Colorado, in Uzbekistan or in a home-school situation,” said William Fitzsimmons, dean of admissions and financial aid at Harvard. Fitzsimmons said that the university has admitted 14 home-schooled students set to graduate in the classes of 2005, 2006 and 2007.

‘It's not a panacea’

While children like Alyssa Elmore have blossomed with the help of home schooling, many home schoolers concede the practice requires enormous effort for all concerned and is not for everyone.

“It doesn’t fit all kids,” Marshall said. “Home schooling is for highly motivated kids who want to learn and don’t need the daily accountability.”

The need for high motivation extends to the parents as well. “The [students] who stay are the ones whose mothers love what they’re doing,” Marshall said. “If you don’t have the parent involvement, they’re short-changed. It’s a huge commitment.”

The bottom line for many experts is that every family brings to the table a different opportunity for success at home schooling.

“It depends on the relationship between the parent and the child, the parents’ skill set, their resources and what the kid is getting in terms of socialization,” says Dr. Arthur Levine, president of Columbia University’s Teachers College.

“It’s a labor of love,” said Ferrall, the former attorney from Darien, Conn. “You have days when you want to tear someone’s hair out — or your own. It’s especially hard with a toddler. You turn around and there are six rolls of toilet paper in the toilet, or someone is drawing on the walls.

“It’s not a panacea,” she said. “I don’t think there’s any option that’s a perfect answer, a never-never land. People tend to romanticize; I know people who have these romantic notions that homeschool families are better families, that home-schooled kids are better kids. I don’t think you have to overmake the case. It’s just a valid educational option.”