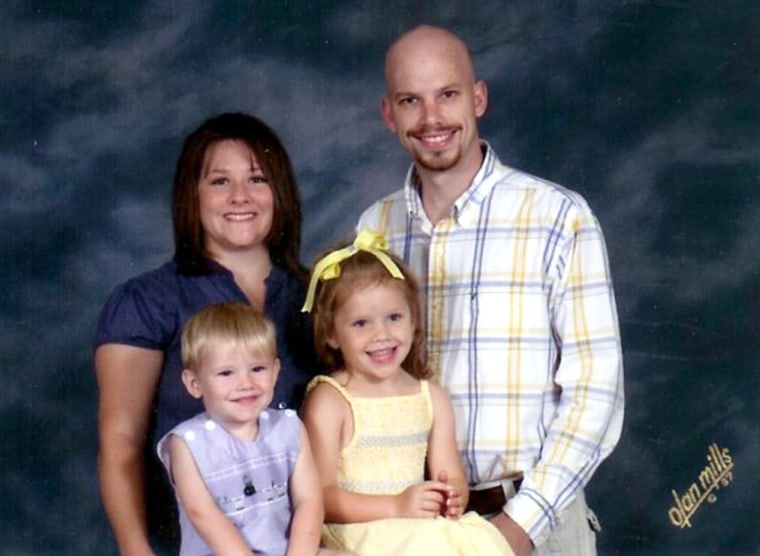

A 4-year-old Mississippi girl is eating Lucky Charms cereal and singing Hannah Montana songs again, three weeks after a severe swine flu infection landed her in intensive care and jeopardized the healthy preschooler’s life.

Doctors expect Isabella Ragan to recover completely from pneumonia and lung surgery, but she is an example of what scientists say are rare but possible complications of H1N1 influenza infections — and what her parents say was their worst nightmare.

"This was emotionally crazy," said Isabella's mother, Kristina Ragan, 23, of Tishomingo, Miss. “The swine flu part wasn’t that bad, but the pneumonia came on top of that and it got the best of her.” Isabella's struggle against the H1N1 virus was by Donna Starkey, a family friend.

Before Sept. 20, Isabella was a T-ball-playing tomboy with no health problems, friends and family members say. But that night, she awoke crying in pain and burning up with a fever that spiked at 105 degrees.

“She was so hot, she wanted me to take her shirt off,” Kristina Ragan recalled.

The next day, doctors tested the child for H1N1 influenza and started her on a course of Tamiflu, the antiviral drug. But the medicine made Isabella sick to her stomach, and not even Popsicles could soothe her. Two days later, she was no better, so Ragan took the girl back to the doctor.

Isabella was referred to the small local hospital, where doctors quickly realized the girl was in trouble. She was breathing rapidly and her oxygen levels were dangerously low. Soon, Isabella was on her way to Huntsville Hospital, an hour away in Alabama, where a pediatric intensive care unit was available.

When she arrived, she was a very sick little girl, Kristina Ragan recalled. “The doctor explained it would get a lot worse before it got better,” she said.

By then, Isabella had become a prime of example of what happens when swine flu goes wrong. The vast majority of illnesses caused so far by the novel flu virus have been mild, government health officials say. But in a rare proportion of cases, previously healthy people — particularly children and young adults — have become seriously ill.

A new government analysis shows that one in four people sick enough to be hospitalized with swine flu last spring had to be admitted to intensive care units and 7 percent of them died. Half of those treated in the hospital were children or teens, which is unusual. Seasonal influenza typically strikes down elderly adults.

Since April, 76 children younger than 18 have died following H1N1 infections, according to Dr. Anne Schuchat, director of immunization and respiratory diseases for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That compares to a between 46 and 88 deaths from seasonal flu in a typical year, Schuchat said.

Isabella also contracted a secondary bacterial infection, a complication found in nearly 30 percent of people who died between May 1 and Aug. 20 from swine flu, according to a recent CDC analysis.

“It could have gone into a life-threatening condition within a few days,” said Dr. Richard Clay, a Huntsville cardiothoracic surgeon who treated Isabella.

The child was placed on a ventilator, a chest tube was inserted and and she was heavily sedated to keep her from thrashing around and pulling out the equipment. Strong antibiotics worked on the infection, but for a few days, it didn’t look good.

Scraping scar tissue off of the lungs

Clay, the surgeon, said Isabella had developed a pleural effusion, a collection of fluid between the layers of tissue that line the lungs and chest cavity, plus a film of scar tissue on the surface of her lungs. It’s a rare complication of the flu and a condition typically seen in adults, but not in children, he said.

The only treatment is to go in and scrape and peel the scar tissue off the lungs, Clay said. Otherwise, the scarring can harden and prevent the lungs from fully expanding, leading to further illness and, possibly, death.

In Isabella’s case, however, the child improved quickly after the invasive surgery. “Little kids, they bounce right back,” said Clay, who expects the girl to make a full recovery.

Isabella headed home last weekend, returning to a small community that has changed its mind about the seriousness of swine flu said Donna Starkey, a family friend.

“We thought it was hype,” she said. “But it can happen to you.”

Starkey has set up donation jars around town and an account at a local bank to help the Ragans pay Isabella’s medical bills. Her father, Jonathan Ragan, 23, is a welder at a local Caterpillar plant and has good insurance, said Kristina Ragan. Still, it looks like the family will owe at least $2,000 in out-of-pocket expenses for the child’s care, she said.

The young mother says she feels “very blessed” that her daughter survived the pandemic infection. But in a move that illustrates another swine flu trend, Kristina Ragan said that despite Isabella’s emergency illness, she probably won’t have her 2-year-old son, Christopher, immunized against swine flu.

“You just hear all the critics talk about it,” Ragan said. “I’m so nervous about it. I just don’t know what to think."

About a third of U.S. parents oppose the H1N1 vaccine, despite government efforts to encourage it, according to an Associated Press-GfK released last week.

But others in Isabella's close-knit community may reconsider the shots after seeing what the Ragans went through, said Starkey, the family friend.

"This is a bad germ," she said. "It almost took this baby's life."