The orbiting sister spacecraft to two NASA probes that slammed into the moon last week has beamed home images and temperature maps of the two intentional crashes.

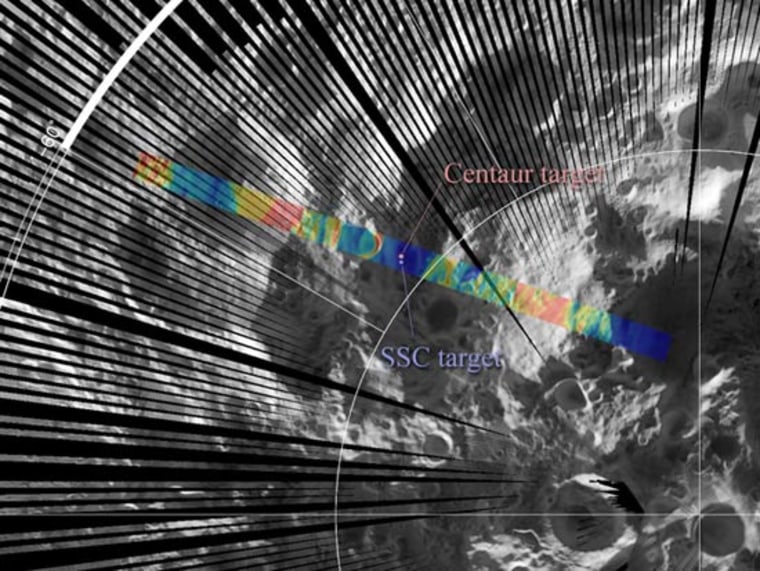

The Diviner instrument aboard NASA's powerful Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter took infrared observations of the impact, flying over the moon crash site of the agency's LCROSS probe and its Centaur rocket stage about 90 seconds after impact at a height of about 50 miles up.

The LCROSS mission is aimed at detecting signs of water ice in the permanently shadowed craters at the moon's south pole by purposely crashing spacecraft into the lunar surface.

The mission's 2.2-ton empty rocket stage walloped a crater called Cabeus at 7:31 a.m. EDT on Oct. 9. Four minutes later, the LCROSS shepherding craft followed suite.

After the impact, Diviner observed the site on eight successive orbits, and obtained a series of thermal maps before and after the impact at approximately two hour intervals.

Diviner is an instrument that maps the surface temperature of the moon in the infrared range of the light spectrum. The thermal maps taken of the Cabeus crater last week show the thermal signature of the impact.

LCROSS itself observed the crater made by the Centaur stage impact in its last few moments before its own death plunge. It still remains to be seen, however, whether the crashes created the vast plume of moon dirt that scientists predicted would blast out of the crater up to heights of 6.2 miles, where it could be lit up by the sun and visible to observers on Earth.

So far, astronomers using ground-based telescopes and the Hubble Space Telescope in orbit have not reported seeing any ejecta plume, but have cautioned that more time is needed to be sure.

Scientists hoped to be able to scan that portion of the plume from space and Earth to determine if any water ice was present in the debris cloud. Finding proof of buried water ice — long suggested by the presence of hydrogen-bearing material at the lunar south pole — could be a boon for NASA since it could be a potential resource for future astronauts.

Last month, scientists announced definitive proof that small amounts of water exist elsewhere on the moon in a molecular form attached to lunar dirt.

NASA launched the $79 million LCROSS mission – short for Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite – in June alongside the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.