Government jobs data are only estimates. The "official" numbers don't include everyone who wants and needs a fulltime paycheck.

I want to know why the government/news does not report the unemployment rate correctly? Counting people who are no longer collecting unemployment, never received unemployment because they didn’t qualify or people who are working part time just to have a little income - it’s more like 19-22 percent. Why don’t they report honestly?

- Ruth W., Texas

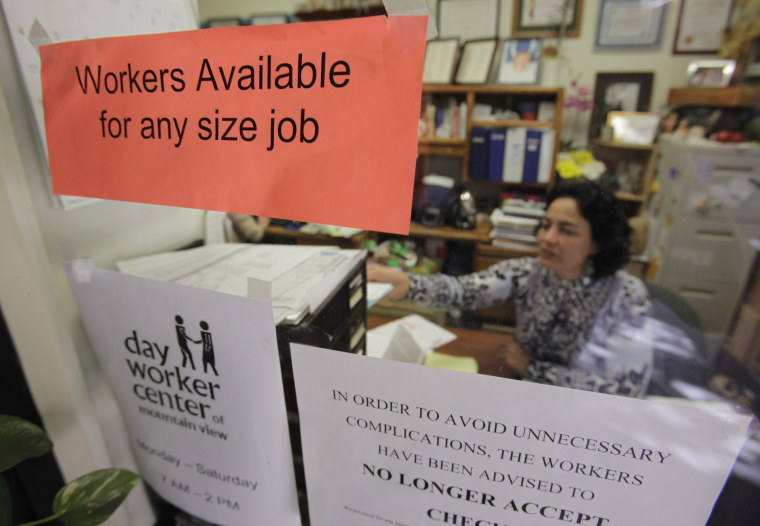

The data is there if you’re willing to dig for it. Unfortunately, as you point out, the “official” unemployment rate badly understates just how truly awful the job market is right now. And since most news reports rely on that “official” number, the real picture is not widely understood.

One reason for this is that discussions about the “real” unemployment rate often degenerate into a rant about the government’s inability to collect accurate statistics. As we’ll see shortly, the data are all there for anyone who wants to look.

As for why this story isn’t reported “honestly,” we tend to give the participants the benefit of the doubt. It’s entirely possible that government statisticians put their thumb on the numbers to make them look “better” than they really are. In our experience, the folks at the Bureau of Labor Statistics take their work seriously and try to get it right. So do most of the news outlets that report the “official” number every month. Unfortunately, in a deep recession, that number just doesn’t tell the whole story.

So let’s take a deeper dive past the so-called “headline” number. The BLS publishes various series of jobs data every month, based on two separate surveys. The “household” survey, which covers only 60,000 households a month, asks people whether they have a job, or are looking for a job, or have given up, or gone back to school, or retired.

The problem starts with the official definition of who is unemployed. For example, if you’ve decided that you’re never going to find a job like the one you lost, and you go back to school to get retrained, you’re not in the work force, and you're not unemployed. Likewise, if you’re in your late 50s, and every potential employer tells you you’re just too old or overqualified, you may give up looking and hope your savings will carry you over until you can collect Social Security. In that case, you’re considered “retired” — again, not unemployed.

Since 60,000 households is about four one-hundredths of one percent of the total work force, the results are then subject to a variety of statistical adjustments, just like any survey. Same goes for the separate “establishment” survey, which contacts roughly 150,000 business and government agencies to find out how many people are on the payroll that month. It’s a little broader, which is why most people believe the payroll survey is more accurate. But it still gets hit with a heavy round of adjustments. And that’s when things start getting a little murky.

When the economy is humming along smoothly, these adjustments tend to be relatively minor. But in the worst job market since the Great Depression, the data get much more difficult to pin down. The payroll survey for last month, for example, showed 263,000 jobs lost. But the household survey logged a drop of 710,000.

Worse, the BLS announced last month that it probably understated job losses this year by more than 800,000, in part due to an adjustment known as the “birth/death” model that tries to estimate the number of small businesses that go in and out of business each month. It turns out that in a deep recession the model doesn’t work very well.

Even in good times, the adjustments applied to the data tend to understate people who are what you or I would describe as unemployed. The BLS publishes the data showing how these adjustments are being made, though. So let’s take a stroll through Table A-12 where you’ll find “alternative measures of labor underutilization.”

The “official” number, also known as U-3, includes people who don’t have a job, “have actively looked for work in the prior four weeks, and are currently available for work.” By this definition, if you’re not looking for work or working part-time, you’re not unemployed.

The next broadest measure, U-4, adds “discouraged workers” who have given up looking. As of last month, that jobless rate was 10.2 percent. The next measure, U-5, which hit 11.1 percent last month, adds in “all other marginally attached workers.” That’s BLS-speak for “persons who currently are neither working nor looking for work but indicate that they want and are available for a job and have looked for work sometime in the recent past.” The broadest measure, U-6, adds in people who are “employed part time for economic reasons.” That rate hit 17.0 percent last month.

So the data is available if you’re willing to dig a little. There are plenty of economists and analysts who take issue with the “official” number. John Williams, who runs a Web site called Shadow Government Statistics, does his own calculations each month that adjusts U-6 to include an estimate of the number of “long-term” discouraged workers - those who have been in that category for more than a year - and fall off the BLS radar. By his count, the unemployment rate hit 21.4 percent last month.

In the end these are only estimates. But it seems clear the "official" estimate is not a true reflection of the number of people who want and need a fulltime paycheck but don't have one.

We’re hearing a lot of talk these days about how “the Great Recession is over.” But it’s hard to see how we can have an economic recovery if more than one in five people aren’t earning enough money to pay the bills.

I need to find the closing prices of several stocks at certain times in the late 90's and early in 2000, 2001 and 2002. Where can I find this information? If you can help me, I'll love you forever.

-Charlyne O., Miami, Fla.

Historical stock quotes are available for free on a number of financial Web sites. Here’s how to find them on Google Finance. On this page, enter the stock symbol for the historical quote you’re looking for. You’ll get a chart showing the last few days trading.

Way over on the left, fourth line down from the top, click on “Historical prices.” Now you’ll get a page showing recent daily quotes for the Open, High, Low and Close, along with the volume of shares traded. To find the closing price for a specific date, reset the date range on the right side of that grey bar above the quote table and click on “Update.”

If you’d like to download a range of quotes to a spreadsheet, click on the link under the chart on the right.

And thanks for the kind words. It’s always nice to know the Answer Desk is helping readers. (Still, forever is a long time, Charlyne.)