Secretary of State Colin Powell’s effort to present irrefutable evidence that Iraq continues to defy U.N. disarmament demands relied on a multimedia presentation of communications intercepts, satellite photos and accounts from both spies and defectors. He laid out the U.S. case in a steadily paced, 90-minute presentation to the U.N. Security Council and, via television, to the world. But Powell’s ability to strengthen the U.S. coalition through the forum of the United Nations may rest less on the actual strength of his presentation than on the world’s willingness to accept the U.S. case at face value.

POWELL OPENED by restating previous U.S. charges and reminding the United Nations of its own actions. It is a strategy used in September by President Bush, who challenged the United Nations at that time to enforce its own resolutions.

“This body places itself in danger of irrelevance if it allows Iraq to continue to defy it ... indefinitely,” Powell said.

“Resolution 1441,” the secretary continued, “gave Iraq one last chance, one last chance to come into compliance or to face serious consequences.” He emphasized that Resolution 1441, approved unanimously by the Security Council in December, put the onus on Iraq to prove its innocence.

“Inspectors are inspectors — they are not detectives,” he said.

INTERCEPTS, SATELLITE PHOTOS

He then reviewed a litany of evidence, some bolstered by audio and visual aids, others more vaguely sourced, arguing that “other sources are people who have risked their lives to let the world know what Saddam Hussein is really up to,” presumably a reference to spies inside Iraq.

The evidence included communication intercepts with visual English translations of conversations between Iraqi military officers. The conversations suggested that, ahead of visits by U.N. inspectors, Iraq took pains to cleanse targeted sites and, in another intercept, army manuals that referred to “nerve agents.”

“This effort to hide things is not one or two isolated events. It is part and parcel of a policy of evasion that goes back 12 years,” the secretary said.

MORE AMMO ON AMMO

Powell unveiled photographs of ammunition bunkers in Taji — both before and after U.N. inspectors arrived at the site. The secretary noted what he described as decontamination trucks and leak detection equipment outside each one in the earlier photos, and then the “cleansed” bunkers on Dec. 22, once it became clear that U.N. inspections would resume.

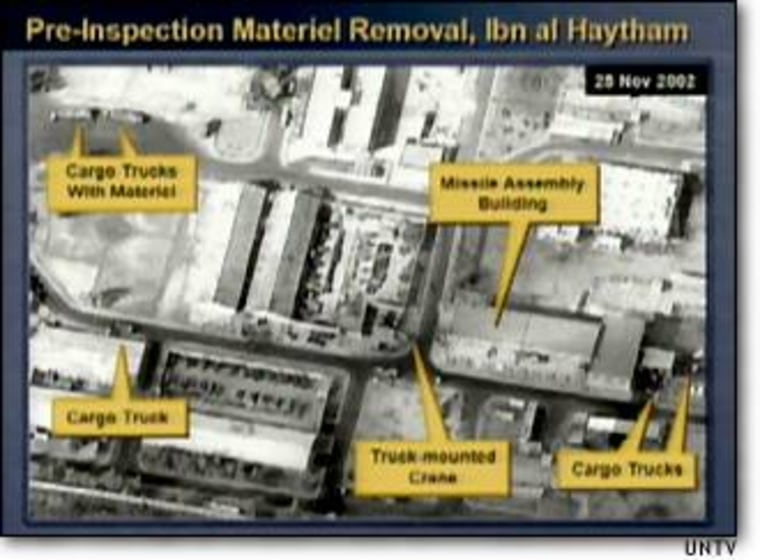

“In November 2002, just when the inspections were about to resume, this type of activity spiked,” Powell said. He then showed images of cargo trucks allegedly moving ballistic missile components and chemical weapons materials from a suspected weapons production site. He contended that such movements took place in “close to 30 sites.”

“We don’t know precisely what Iraq is moving, but the inspectors knew about these facilities, and Iraq knew they would be coming,” the secretary noted.

“We have firsthand descriptions of biological weapons factories on wheels and on rails.” Powell then showed artist renditions of these alleged facilities based, he said, on interviews with a former Iraqi engineer who worked on them.

He added detail to allegations that Iraq was also pursuing nuclear weapons, charging that Baghdad’s efforts to purchase highly tooled aluminum tubes and centrifuge motors in Europe — a charge based on British intelligence — proves Saddam is pursuing nuclear weapons.

IRREFUTABLE?

Powell characterized the evidence proffered, including satellite photographs, radio and telephone communication intercepts, reports from defectors and other items, as irrefutable proof that “Saddam Hussein and his regime have made no effort — no effort — to disarm.”

The presentation did not have the impact of a similar presentation made by former U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson in 1962, when he showed aerial photographs exposing Soviet missile deployments during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, experts said.

But based on the evidence he had, Powell’s performance was “masterful,” said Bruce Berkowitz, a senior analyst at RAND and a former CIA analyst.

“He showed patterns, he showed logic, and he framed the argument,” he said. And Powell succeeded in using newly declassified intelligence to shift the issue from whether U.N. weapons inspectors were finding banned weapons to a focus on signs that Iraq was not complying with U.N. resolutions requiring disarmament, Berkowitz said.

As for the portion of Powell’s address dealing with links between Iraq and terror groups, the case was stronger than before but still not definitive, said Lawrence Korb, director of national security studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It did not show clear and present danger,” Korb said. “Everybody agrees Saddam is a bad guy,” he added, but there was no “smoking gun” such as evidence showing Saddam gave a weapon to al-Qaida or possessed a chemical or biological weapon.

“I think it moved the ball a little bit” among doubters toward the U.S. viewpoint, Korb said.

Oded Granot, an expert on Arab affairs for Israeli Channel One television, said Powell had offered circumstantial evidence with a cumulative weight greater than its parts.

What Powell had shown was “not the smoking gun but the place the gun was laid before being removed ahead of inspections,” Granot said.

Ellie Goldsworthy of London’s Royal United Services Institute said Powell had made a convincing case.

“I think it will be a wakeup call to some of the countries sitting on the fence. I think there will be some squirming in the seats today,” she said.

But Powell’s presentation appeared unlikely to touch off a stampede of nations eager to join a “coalition of the willing,” as President Bush has characterized it. Those deeply opposed — nations like Germany and Greece in Europe, or nations like Egypt and Syria across a wide swath of the Muslim world, do not appear inclined to rethink their opposition on the strength of evidence gathered by the CIA or National Security Agency. Indeed, the resentment toward these intelligence bodies runs so deep in some parts of the world that their role in collecting the evidence may actually discredit the evidence.

SO FAR, STATUS QUO

For those nations on the Security Council — 15 in all, including the four other veto-wielding permanent members, Britain, France, Russia and China — the first chance to address Powell’s comments came directly after Powell finished his presentation.

A key opponent to military action, France, maintained its opposition to war against Iraq despite Powell’s presentation, instead proposing that weapons inspections be strengthened.

French Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin suggested tripling the number of inspectors and placing a full-time monitor in Baghdad to oversee the process.

“The use of force can only be a final recourse,” de Villepin told a special Security Council session. “We must move on to a new stage and further strengthen the inspections.”

De Villepin said France would carefully review the evidence provided by Powell, but he emphasized that inspections were working and had resulted in major achievements.

Still, he acknowledged there was more Iraq could do to cooperate with a beefed-up inspections regime to avert war.

Another permanent council member, China, followed suit, saying that U.N. arms inspectors should be given more time to carry on with their work in Iraq.

“We should respect the views of the two (U.N. inspection) agencies and support the continuation of their work,” Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan said.

Britain, all along Washington’s closest ally on the Iraq issue, dismissed as futile on Wednesday calls to give more time to United Nations’ weapons inspectors in Iraq, saying Baghdad was in material breach of the key U.N. disarmament resolution.

Foreign Minister Jack Straw emphasized the seriousness of Iraq’s situation and warned that “time is very short.” He also played down apparent differences between the United States and Britain over the depth of the connection between Iraq and al-Qaida, saying that Baghdad had created a “permissive” atmosphere for al-Qaida operatives.

Equally consistent was Iraq’s Ambassador Mohammed Aldouri, who gave the final address after Powell’s presentation. Aldouri offered a point-by-point rebuttal to Powell’s presentation, which he said was “utterly unrelated to the truth.”

He dismissed the sound recordings as not authentic and maintained that “Iraq is totally free of weapons of mass destruction,” as Baghdad has said all along.

“Mr. Powell could have ... presented these allegations directly to UNMOVIC and IAEA...” Aldouri said, arguing that rather than bringing the charges to the public, he should have “left (the inspectors) to work in peace and quiet to ascertain (the truth) without media pressure.”

Powell’s presentation was an attempt, said Aldouri “to convince public first and world public opinion in general to launch a hostile war against Iraq.”

ACTION VS. WORDS

Yet measuring the impact of Powell’s case will not be as simple as listening to these statements. The established positions of the four other permanent members may not shift after this meeting.

Sudden public shifts in carefully devised diplomatic positions is not the norm. Britain’s robust support of the U.S. position, for instance, was unlikely to waver at this sensitive moment even if privately some in the British Cabinet would prefer to give inspectors more time on the ground.

Even if Russia, France or China indicates a new inclination to bless the use of force now, such a move would result from a fundamental policy-making switch rather than a simple reaction to the case presented by Powell.

Any shifts toward the U.S. position now might simply reflect resignation on the part of these states that they appear powerless to halt war if the United States truly intends to proceed. Using Powell’s speech as cover to soften their opposition could be viewed as a practical move at this juncture.

“In the end, none of the permanent members wants to be on the wrong side of a war whose outcome appears to be little in doubt,” a European diplomat told MSNBC.com before the speech. “They are not so opposed that they can’t imagine spinning it as a victory for multilateralism after the fact.”

MSNBC.com’s Kari Huus, The Associated Press and Reuters contributed to this report.