The multisyllabic name-calling and diplomatic back-stabbing going on within the NATO alliance is shedding little light on the most important issue of the day: whether a war against Iraq right now would be justified. At a time when the world’s most powerful military alliance should be examining its ability to handle the threats of the 21st century, its leaders — American, European and otherwise — instead take turns questioning each others’ morality, manhood and national character.

THERE IS no one wearing a white hat in this screenplay. Washington’s outright disdain for debate or international opinion feeds paranoia about America’s long-term intentions on the European continent. In turn, the seemingly boundless and arguably unwarranted faith in collective security methods and U.N. monitoring schemes on the part of some European countries has caused the Bush administration to write off the once-great world capitals Berlin, Paris and Brussels as irrelevant.

Interestingly, a compelling case can be made that both sides are at least partly right. The Franco-German argument that al-Qaida would probably be a better focus for America’s might than Iraq is one that finds agreement within the U.S. military, if not among the civilians that run the Pentagon. “I think it’s the wrong war at the wrong time,” a senior Navy officer told me. “I think we will win the battle against Saddam, but will that cost us the larger war on terror? A lot of flag rank guys are asking that question.”

At the same time, recent history is filled with examples of misplaced faith in international peacekeeping and containment efforts. Bosnia, above all, is cited as proof by Bush administration hawks that European powers cannot muster the backbone to take tough action against despots. European military officers I covered during that conflict conceded their frustrations to me.

“Bosnia set back the idea of unifying European defense and foreign policy by decades,” a British army officer told me in 1995. “We all have ‘rules of engagement’ to blame, but the fact is, when people’s lives were at stake, we hid behind them rather than push for their revision. It smacks of Czechoslovakia, 1938.”

THE QUARRELLING COUPLE

The Franco-American shoving matches that typify this trans-Atlantic friction hardly represent a new development. France never recovered from the triple humiliation of capitulation, occupation and collaboration during World War II, despite Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s decision to allow DeGaulle’s “Free French Forces” lead the march into liberated Paris.

France soon perceived U.S. policy a deliberate effort to prevent it from re-emerging as an independent force in world politics after the war. Many there to this day blame the United States for not aiding French attempts to hold onto Algeria and Indochina (though the American perspective on the latter is quite different) and for thwarting an Anglo-French-Israeli attempt to prevent Egypt from nationalizing the Suez Canal.

By the early 1960s, DeGaulle was demanding that France wean itself from “American tutelage” and by the middle of the decade had ordered that all U.S. troops be removed from French soil. (This led to one of the most clever responses in American diplomatic history. Secretary of State Dean Rusk, requesting clarification of the French demand, asked whether the order included removal of those buried in French soil, too.)

Despite this internal quarreling, France never left NATO, though it did drop out of the alliance’s integrated command for a several decades. Still, Washington counted France as a reliable ally throughout the Cold War — particularly on the U.N. Security Council. As unpleasant as “American tutelage” seemed to the French, the Soviet version of friendship struck them as a great deal worse.

With the end of the ideological divide in Europe, however, French policy began quickly to reorient itself. As early at 1996, the incoming French foreign minister, Herve de Charette, described the role of French foreign policy as “preventing American hegemony.”

YES, BUT HOW?

For France, and for other European powers like Germany, Greece and Belgium who have ceded sovereignty to the European Union during the 1990s, the logical way to control a superpower is through international legal systems.

“It is only natural to expect that a country with the technological, military and diplomatic resources of the United States is inclined to try and ‘fix’ problems — whether Balkan crises, missile threats or rogue states — whereas countries with fewer such resources at their disposal try to manage them,” writes Philip Gordon, director of the Center on the United States and France at the Brookings Institution.

From this reality, he notes, flows Robert Kagan’s now-famous line that “Americans are from Mars, Europeans are from Venus” — a reference to an early 1990s self-help book on the differences between men and women.

In the 1990s, when French complaints drew the ire of other Europeans, as well, Kagan’s idea might have seemed arrogant. Today, the analogy is pretty good.

Take the case of Germany, which for most of its history was hardly anyone’s idea of a “Venusian.” As recently as the Kosovo war the Germans, citing their historic duty to oppose the kind of genocide they once perpetrated in Europe, had been aggressive advocates of the use of force. In the relatively short time since the 1999 Kosovo conflict, however, Germans, too, have grown wary of American power.

Polls showed a majority of Germans supported the American war in Afghanistan, but early Bush administration snubs of Europe over trade, the environment and other issues had prepared the ground for trouble.

ABOUT FACE, MARCH!

By 2002, German public opinion turned against America, with many criticizing “extra-legal” actions like the detentions of Afghan prisoners without redress in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and the killings of suspected al-Qaida suspects in Yemen. There is deep dismay with American policy toward the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, too, which is seen as so pro-Israeli that is actually encourages Israeli arrogance.

And throughout, Washington’s public position that it would go to war for national interest regardless of what the United Nations says runs counter to everything Germans have been taught — in large part thanks to American de-Nazification efforts — since 1945.

German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder somewhat cynically tapped into this to win re-election. But his position reflected public attitudes more than it shaped them. They don’t want to “fix” Iraq; they want to manage it.

Today, the United States finds itself confronting a fairly united German and French faction inside Europe that is adamantly opposed to many of America’s top foreign policy priorities. Viewed from the outside, this strikes some as ironic.

“They deserve each other,” a Mexican diplomat at the United Nations says of America and its European allies. “They are equally arrogant. They bear equal guilt for how the world views their motives. The only real difference is that one of them can call the shots and the other can only call bluffs.”

NO BLUFF THIS TIME

This fact - Europe’s relative inability to act alone (or together) in the military sense - fatally weakens their influence on Washington. The last-minute efforts by France, Germany and now Russia to prevent a conflict on America’s terms look half-baked because they are half-baked. These powers understand that, if the United States has now crossed the Rubicon and is willing to defy the United Nations, they are powerless to prevent it.

And it is their own fault. Even without Russia’s economy and military know-how, the European Union’s GDP of $8.5 trillion and its population of 377 million people should easily be able to create a military force on par with the smaller United States. With such a force, European alternatives — aggressive, militarized arms inspections, for instance, might have some hope of succeeding. Without that force, their words are just that: words.

These complexities — Europe’s bantamweight military power and America’s frustration with partners who speak loudly but carry two dozen small sticks — are ignored in the larger debate.

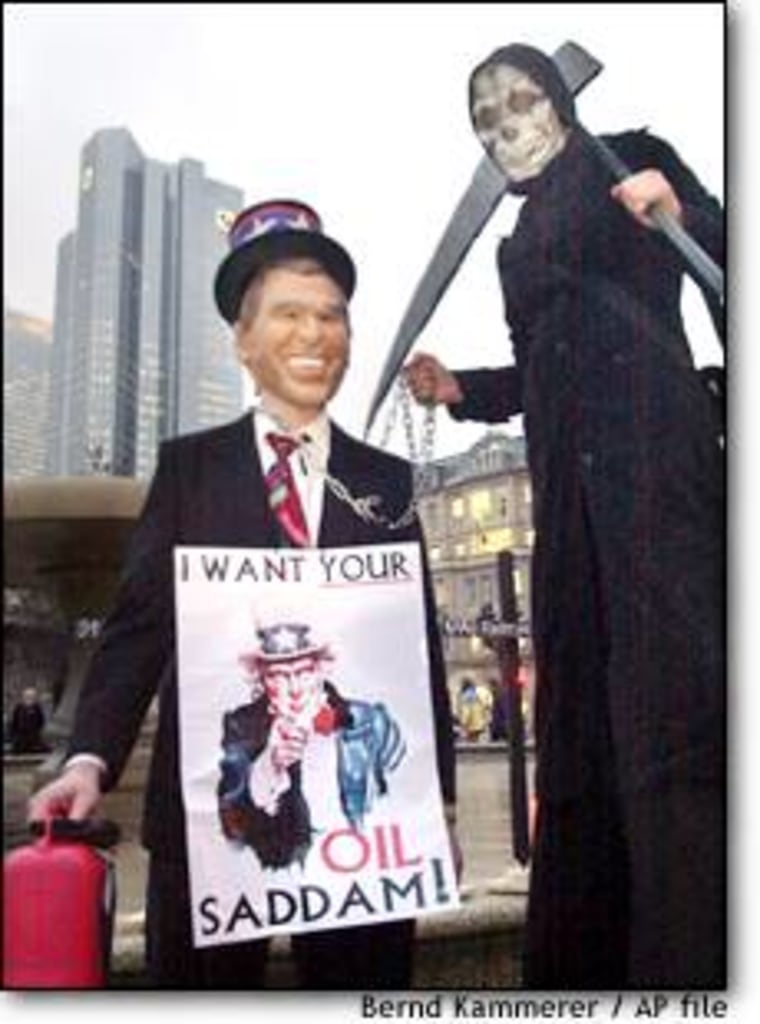

In the meantime, the world is left to watch as the most serious issue of the new century is reduced to this idiotic spectacle: a reckless, bloodthirsty cowboy vs. an ungrateful, cowardly bunch of Euro-weenies.

How Osama bin Laden must be rejoicing.

Mail your thoughts to Michael Moran, request to join (or be removed from) his email notification list, and check out his daily roundup of the international press, “War of Words,” which also airs daily at 10:25 AM ET on MSNBC cable.