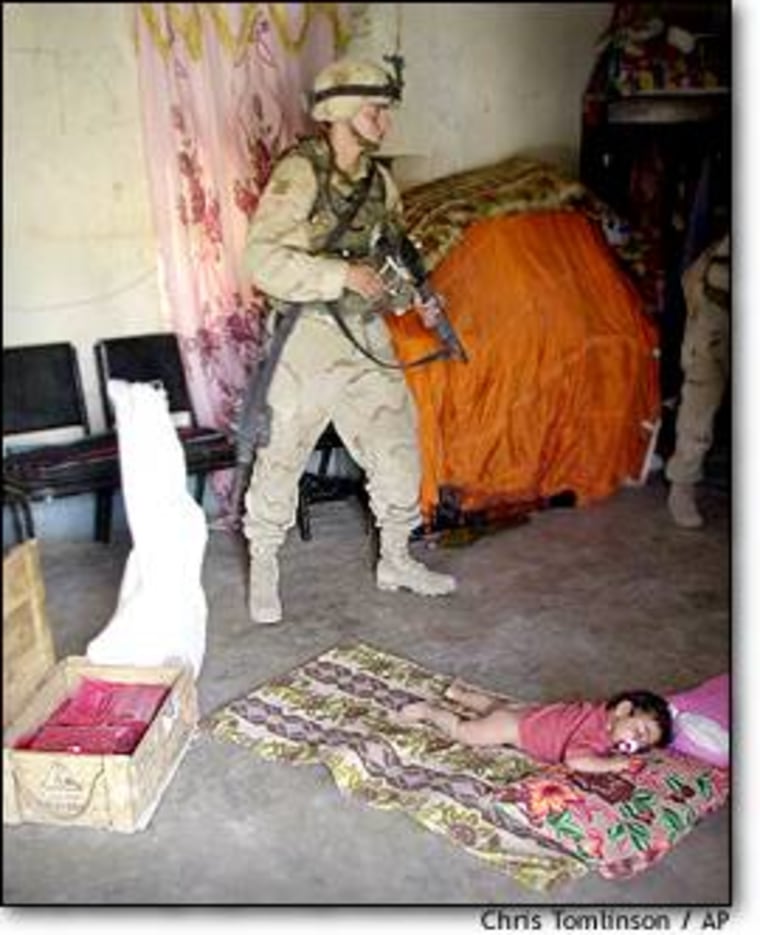

For the commanders of U.S. troops in Iraq who warned “we don’t do body counts,” the postwar occupation is proving to be a trying time. Just over five weeks since President Bush declared major combat operations to be at an end, 41 American soldiers have died, 11 in hostile fire and 30 in accidents. The latest death was that of an Army infantryman shot dead Monday at a check post in the western desert. While the United States and Britain lost fewer troops than they had feared while vanquishing Saddam Hussein’s regime, the postwar U.S. death rate, now averaging more than one soldier per day, is giving pause to military planners and could threaten public support for the years of occupation now envisioned by the Bush administration.

THE POLITICAL DEBATE over the Iraq war has shifted from the right of the United States and its allies to launch such a pre-emptive war unilaterally to the more nuanced question of whether the Bush administration and British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government in Britain skewed intelligence to exaggerate the threat posed by Iraqi chemical and biological weapons. In the coming weeks, congressional hearings, a parliamentary inquiry and investigative reporting by the world’s media will drive home this question: Did the United States and Britain launch a war to pre-empt a threat that did not exist?

Whatever the answer, one thing is certain: The specter of American troops coming home in body bags is one that haunts every president. That fact is particularly salient when the deaths occur during “non-combat” operations such as military police actions, peacekeeping missions or postwar occupations.

“I think it is bound to have a kind of wearing effect on support for the mission, and thus on the president’s popularity,” says Professor John Mueller of Ohio State University, who has specialized on the effects of war and foreign crises on presidential job ratings. “Eventually, the question in the public’s mind will be: Is it worth helping these people, who don’t seem to even want us there, if it is going to cost American lives?”

POLLS AND POLICY

Political analysts and pollsters agree there is no significant data yet suggesting that the postwar difficulties that U.S. troops have faced is rubbing off on the president. Polls do show that Bush’s “job approval” ratings are down from their wartime high in the 70 percent to 72 percent range to the mid-60s, but analysts are quick to note that his current rating is very solid for a president presiding over a shaky economy.

But those same polls show that, when asked, Americans are wary of the Iraq occupation. Particularly telling was a Washington Post-ABC News poll from mid-April, when the situation on the ground was fairly good and the postwar afterglow still favored the administration. The poll asked whether respondents feared getting “bogged down in a long and costly peacekeeping mission in Iraq.” A majority did fear such a possibility, with 31 percent saying they were “very concerned,” 42 percent saying they were “somewhat concerned” and only 19 percent saying they were “not too concerned.”

“The problem, I think, in peoples’ minds is that the American presence doesn’t seem to have a logical end to it,” says Lee Sigelman, a George Washington University professor of political science. “The White House, and for years the Republican Party, has made a clear and fundamental commitment not to enter into conflicts without an exit strategy. When the war euphoria wears off, they better be able to show what that strategy is.”

THE MUDDLE FACTOR

The war in Iraq, however, cannot be viewed without the context of the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. No evidence gathered by U.S. intelligence so far conclusively links Iraq directly with those attacks, nor has there been any convincing case publicly made to suggest that al-Qaida and Saddam’s regime worked as partners against the United States.

But advocates of both theories have made their mark on public consciousness. Polls consistently show that Americans have had difficulty distinguishing between the war against al-Qaida and the war in Iraq — a tendency encouraged by the administration. On May 1, the day Bush landed on the USS Abraham Lincoln and proclaimed major combat operations were over, he also said “the battle of Iraq is one victory in a war on terror that began on September the 11, 2001 — and still goes on.”

“Certainly, the complexity of these issues will give the administration more time to get things straight,” Sigelman says. “Some polls recently suggested that 40 percent of the public also believed that weapons of mass destruction already have been discovered in Iraq, when clearly that is a very sore point with the White House.”

Indeed, the administration has gone to great pains to play down the importance of finding weapons of mass destruction, just as senior officials quickly stopped mentioning Osama bin Laden by name once it became clear that he had not been killed or captured during the Afghan war.

Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, a leading hawk inside the administration on Iraq policy, told Vanity Fair recently that in the swirl of prewar internal arguments about Iraq, the decision to stress weapons of mass destruction was a compromise of sorts.

“For bureaucratic reasons, we settled on one issue, weapons of mass destruction, because it was the one reason everyone could agree on,” Wolfowitz said in the interview.

But funerals for soldiers, orphans and widows won’t be lost on the public. The administration still has some time to stabilize the situation in Iraq — perhaps a period of several months — before the daily toll of American dead and wounded seriously begins to threaten Bush’s political standing.

“In the short term, it would take a major incident — the deaths of 10 to 20 American soldiers in some catastrophic attack — to focus the question,” says Mueller. “Unless that happens, you are not likely to see Democratic candidates try and score points against it, and the average person is far more concerned with the economy. So, they’ve got time.”

Michael Moran is senior correspondent at MSNBC.com.