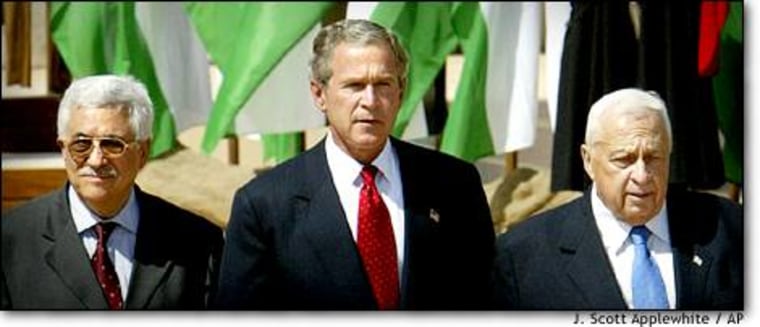

Three leaders, three substantive, even somewhat startling statements of determination to see a settlement to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict finally concluded. Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Palestinian Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas and U.S. President George Bush infused their words with optimism after concluding their first summit meeting in the Jordanian city of Aqaba on Wednesday. But their words are being scrutinized and deconstructed by Jews, Arabs and Americans with myriad opinions on how and even if the conflict should end. For all three men, the coming weeks will seriously test their ability to make the situation on the ground jibe with the lofty vision set forth in Aqaba.

EVEN IF WEDNESDAY’S SUMMIT produced no dramatic proclamations, it would have been deemed progress of a sort merely for being held. Not since the waning days of the Clinton administration in early 2001 has an American president stood with an Israeli and Palestinian leader and spoken of peace.

But, judging from the public statements at the short parley, all three clearly intended to give the impression that the peace process is now fully operable, and, even more importantly, operating with the full weight of each government behind it.

Ascribing deep and concrete meaning to any politician’s public statements can be like trying to paint a cloud. Yet on Wednesday each man said things that went beyond the minimum requirements for the occasion, and certainly there have been such meetings in the past that produced far more desultory claims of enthusiasm.

PLEDGES AND ECHOS

Abbas, for instance, broke new ground in urging that Palestinians “not ignore the suffering of the Jews throughout history. It is time to bring all this suffering to an end.” He also promised to “exert full efforts to ending the militarization of the intifada [uprising]. The armed intifada must end and we must resort to peaceful means to achieve our goals.”

That last statement will be welcomed by Israeli and American officials, though stating it publicly and enforcing it in the shattered and roiling Palestinian territories are two very different things. Indeed, there is a quality of deja vu to some of it, harkening back to statements by Palestinian President Yasser Arafat in the mid-1990s which, in retrospect, have little currency today.

Another qualifier that must be applied is the fact that Abbas serves at Arafat’s whim, a prime minister appointed by an elected president. Bush and Sharon spent the last two years forcefully isolating the former PLO leader, who still lives in a kind of Israeli-enforced quarantine in the West Bank town of Ramallah. But Arafat has repeatedly shown himself to be far from irrelevant as a force within Palestinian politics, and that will necessarily school caution to any pledges Abbas makes.

CONTIGUITY AND AMBIGUITY

Sharon, a figure reviled by many in the Arab world dating to his command of the invasion of Lebanon in the early 1980s, continued to astound observers and confound long-time supporters with his public support for Israeli concessions.

“We can also reassure our Palestinian partners that we understand the importance of territorial contiguity in the West Bank for a viable Palestinian state,” Sharon said, carefully choosing exactly the word — “contiguity” — that even his more dovish predecessor, Ehud Barak, would never utter.

InsertArt(1941432)Past Israeli visions of a future Palestinian state, even that envisioned in the defunct Oslo peace process, generally used the term “entity” instead of state, suggesting an unspecified degree sovereignty. Maps produced by Israel invariably showed several large swaths of Palestinian territory, including Gaza, regions around Nablus and another to the east of Jerusalem, that would be connected only by heavily patrolled highways or tunnels and surrounded by fortified Israeli settlements.

Over the past two weeks, however, Sharon on several occasions, including one before the Israeli parliament, has described the Israeli presence in the West Bank as an “occupation,” a turnaround for the man regarded by many Israelis as the father of the settlement movement. Challenged last week by angry members of his own right-wing Likud Party, Sharon said it was not his job to justify statements he had made in the past, and on Wednesday he used another term bound to cause unease among his more militant constituents — a pledge to dismantle “unauthorized outposts” as a first step, a reference to proto-settlements, often no more than a few trailer homes, that have popped up since the last peace talks collapsed in 2001.

InsertArt(1941431)Perhaps most importantly, Sharon said, “We accept the principle that no unilateral actions by any parties can pre-judge the outcome of our negotiations.”

Again, the wording is legalistic and potentially vague, but that could be taken as a sign that Israel is now prepared to give Abbas and the Palestinian Authority some leeway in battling the militants of Hamas and Islamic Jihad who almost certainly will try to derail any negotiations with a new wave of terrorism. One peace effort after another of the past 15 years has come undone because of such terror campaigns and “targeted killings,” missile attacks, military incursions and Palestinian home demolitions that Israel inevitable launches in retaliation.

SPENDING SOME CAPITAL

President Bush, too, spoke effusively of the process, an indication that he has decided — for now, at least — to expend a significant amount of the political capital he accrued in vanquishing Saddam Hussein on trying to solve the Mideast’s central conflict.

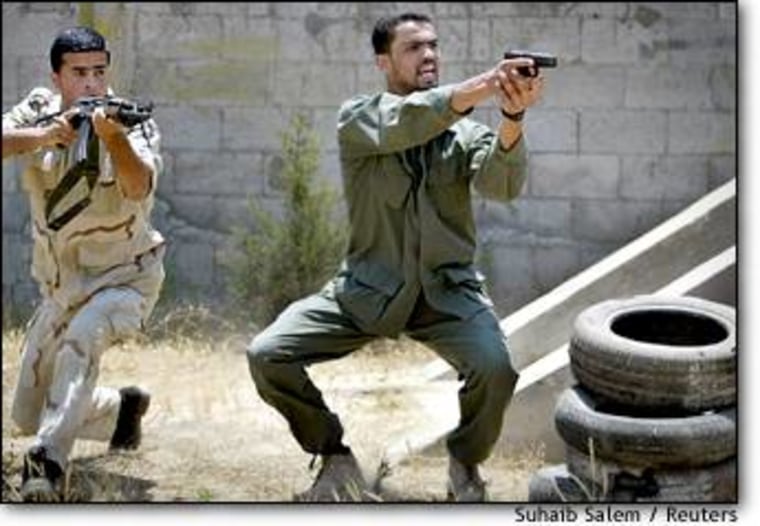

The president, speaking after the Israeli and Palestinian leaders, pledged training and other assistance to the Palestinian Authority, which is struggling to rebuild its security forces after 32 months of violent conflict with Israeli troops that saw 750 Israelis killed, including about 350 from suicide bombings. During the same period, more than 2,350 Palestinians have been killed, including many policemen who fought Israeli troops sent to reoccupy segments of the Palestinian Authority’s territory.

The Palestinian police force that existed before the “new intifada,” as the violence that began in September 2000 is called by Palestinians, has been shattered by Israeli attacks on their barracks, police stations and communications facilities.

Bush singled out Abbas for particular praise, calling him the embodiment of “peace and freedom.” Bush and Abbas met separately with other Arab leaders in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh on Tuesday.

Perhaps the most forthright statement came from Jordan’s King Abdullah II, host of the summit and son of the late King Hussein, who signed a peace treaty with Israeli in 1994. Speaking to a press corps that included all of the Arab world’s newly minted satellite television networks, Abdullah said “blowing up buses will not induce the Israelis to move forward and neither will the killing of Palestinians or the demolition of their homes and their future. All this needs to stop.”

EASIER SAID ...

Whether it does, however, will depend on factors that could be outside the control of Sharon or Abbas.

For Sharon, physically dismantling the “illegal outposts” he referred to Wednesday will be taken as a final sign among his Likud Party that the prime minister’s words are more than just an attempt to mollify an American president who is himself under global pressure to throw his weight behind the peace process after having fought two wars in two years against Muslim nations, first in Afghanistan and then Iraq. The extent to which Sharon can defy his party is an unknown, and Israeli analysts suggest that, if the process did progress and his right-wing coalitions partners began to defect, the left-leaning opposition Labor Party might be coaxed back into a national unity government to shore up Sharon’s political base.

For Abbas, the uncertainties run even deeper. The aforementioned influence of Arafat remains a wild card, and internecine violence within the Palestinian Authority also is a possibility.

By far his greatest challenge will be in preventing suicide bombers by two independent entities, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, or the Al-Aqsa Martyrs associated with Arafat’s Fatah Party, from trying to bomb the process into extinction. Past Palestinian efforts to control these groups were unconvincing to Israeli officials, though the CIA, which had a role in monitoring Palestinian Authority compliance in the late 1990s, always felt that many of the attacks launched during that period were genuinely outside the PA’s control.

Nonetheless, the Israeli public, only gingerly re-embracing the idea of peace talks, may be quick to withdraw its support if such talks appear to be doing nothing to halt the deluge of suicidal attacks against Jews inside Israel. Within minutes of the talks conclusion on Wednesday, Hamas had issued a statement calling them a sell out of the Palestinian cause — a sign that Abbas will have his hands full.

As lofty as the rhetoric might have been Wednesday, the true proof will be in what happens over the next several weeks. As Secretary of State Colin Powell said, “real trust is going to come from performance.”

Michael Moran is MSNBC.com’s Senior Correspondent.