The full attention of the U.S. military, its intelligence agencies and its diplomatic arm, is turning to the hunt for Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks who officials now fear may have escaped to safety as his al-Qaida fighters made a last stand in southeastern Afghanistan. But even as American officials vow to get bin Laden and his top aides, they also are struggling to ensure the hunt itself doesn’t detract from their larger goals: destroying al-Qaida and safeguarding the United States from further attack.

THE FOCUS on catching bin Laden is inevitable and understandable. From President Bush to the media to New York’s graffiti artists, bin Laden’s image now embodies evil to most Americans. The Bush administration made a concerted effort in October and November to play down the importance of catching bin Laden versus the toppling of the Taliban and the crippling of al-Qaida. But in moments of passion, senior officials could not resist playing to the deep desire among average Americans to see this man brought to justice.

“Dead or alive,” said President Bush on Sept. 18. Try as they might, the White House has not been able to convince the rest of the nation that a true victory is possible without bin Laden’s head on a platter.

HISTORICAL CONCERNS

As badly as Americans would like to see that happen, some in the Pentagon are concerned that the emphasis of the war, so far focused on al-Qaida and its Taliban allies, does not get mired in the kind of manhunt that historically has given the U.S. military difficulty.

Defense officials and several military officers interviewed by MSNBC.com all alluded to previous instances where manhunts turned into distractions or even debacles that undermined larger American policy goals.

The most recent instance, the 1993 effort to capture a troublesome Somali warlord named Mohammed Farah Aideed led to a failed raid in Mogadishu that left 18 American soldiers and some 500 Somalis dead. The disaster led to the collapse of the American mission in the East African state, which sank into an period of anarchy that has been exploited by al-Qaida.

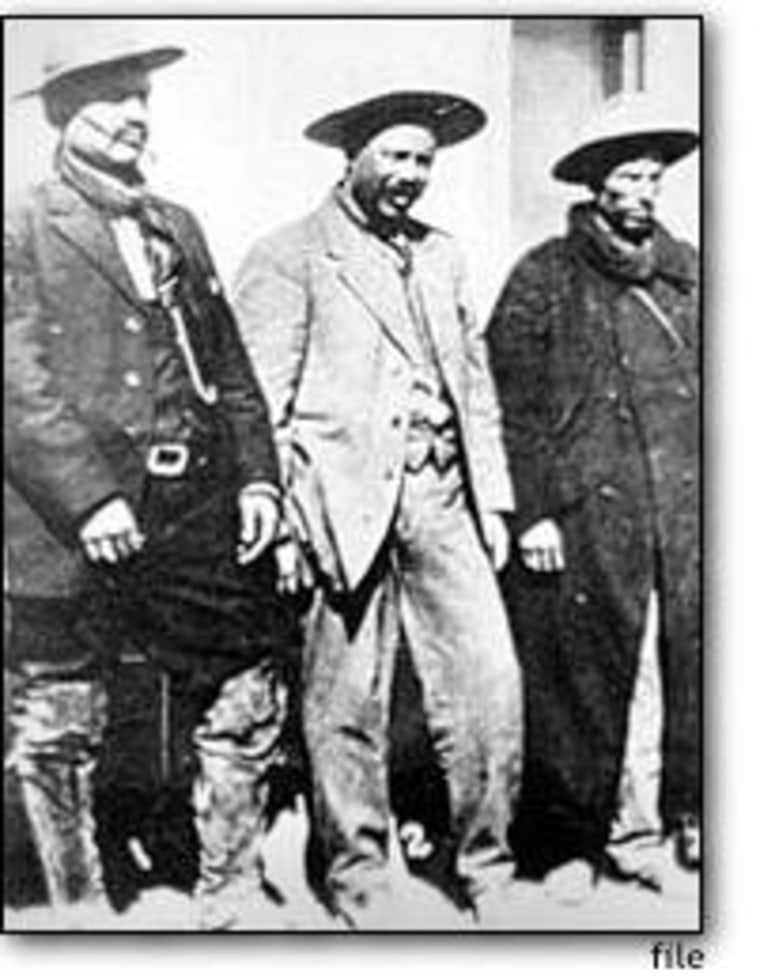

Further back, military historians cite the 1916 manhunt for Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa after Villa’s men raided the border town of Columbus, N.M., and executed 17 Americans. The attack — the last large assault on an American state by a foreign enemy until Sept. 11 - led the United States to send an Army cavalry division into Mexico in pursuit of Villa.

The manhunt was an enormous failure, and the U.S. withdrew in 1917 after suffering 24 dead. The only solace, retrospectively, was that the action provided much needed field experience for two men who would go on to fight in Europe in World War I - Brig. Gen. Jack Pershing, and a head-strong young lieutenant named George S. Patton.

Still, historians note that at a time when the United States should have been preparing for — or even fighting — World War I, it was chasing a Mexican rebel through the arid Sierra Madre.

THE MANHUNT DYNAMIC

One defense official with knowledge of current war planning said the Pentagon is wary of allowing a “manhunt dynamic” to take control of the overall war plan. The larger goals of the war on terrorism, the official said, continue to be far broader than the capture or killing of any one person. “This isn’t Nazi Germany, where you might have ended the war by killing Hitler,” he said. “Cells exist around the world, and we’re concentrating on a rolling scenario with various partners for neutralizing those cells.”

Another official who served in a senior Pentagon post during the Clinton administration said U.S. special forces are not trained in manhunts.

“We tried the man hunt with Aideed and with (Panamanian dictator Manuel) Noriega. We were not very effective. Our guys are not good at going door to door or cave to cave. They are best at busting down the doors and killing people ... but they have to know which door.”

Early on in the war, the United States recognized the danger of allowing public opinion to equate victory over al-Qaida with bin Laden’s death. Officials have gone out of their way to note that even the death of bin Laden and his senior lieutenants would not neutralize the threat that the many al-Qaida cells pose. This is partly because those cells are designed to operate independent of any central command structure - i.e., they already have orders they’re pursuing.

But it also reflects a political calculation. Bin Laden’s death - his “martyrdom,” in the eyes of radical Islamic followers - could well inspire a new wave of less coordinated, but no less deadly, violence.

SUBTLE SHIFTS

After it became apparent last weekend that the saturation bombing of the Tora Bora cave complex had not produced bin Laden, either dead or alive, American policy began a subtle shift. Pressure on Pakistan to carry through with its promises to seal the Afghan-Pakistani border was stepped up - too late in the minds of some officials - and some fleeing Taliban and al-Qaida fighters were arrested.

U.S. officials assume, however, that many more such fighters got through to the untamed autonomous tribal regions along Pakistan’s northern border, leaving the United States once again at the mercy of foreign forces to ferret out any senior al-Qaida men who might be there. One military official, commenting on speculation that the United States might consider pursuing al-Qaida into Pakistani territory, dismissed the idea for now. “The Paks are doing it for us,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “We’re following it closely and helping with intelligence, but right now, there’s no plan to get directly involved there beyond intelligence.”

Beyond Pakistan, U.S. planners continue to eye a half dozen states known to have active al-Qaida cells.

“There are, obviously, a number of countries that have active al-Qaida cells, and Yemen is one,” Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld said Monday at NATO headquarters in Belgium. “Sudan is, obviously, one. Somalia used to be a location where senior al-Qaida officials spent time. There are a number of other locations around the world where that’s the case.” They include Eritrea, Algeria, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Officials believe that keeping a global perspective even as bin Laden and his aides are pursued in Southwest Asia will ensure that the war on terrorism doesn’t deteriorate into a high-tech, high-explosive game of hide-and-seek.