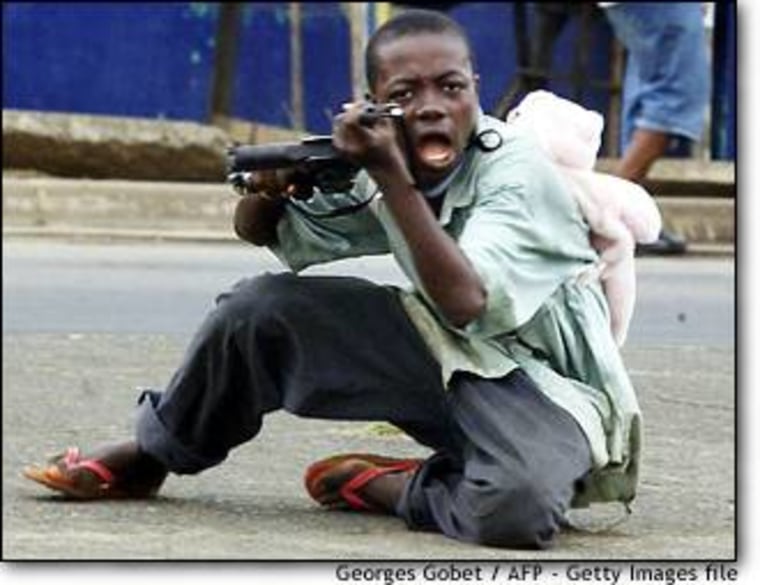

This chilling image was captured by a photographer on the streets of the Liberian capital of Monrovia in late June: A soldier — his eyes dull and his mouth wide open, as if yelling fiercely — aims his AK-47 directly at the camera. On his back he wears a knapsack in the form of a pink teddy bear. The gunman is perhaps 12 years old. The faces of young and lethally armed combatants appear on all sides of Liberia’s conflict, and peacekeepers will have to deal with them as they start their mission Monday to quell the violence.

As fighting has intensified in Liberia’s civil war in recent weeks, aid workers in Monrovia say that rebel groups and government forces have populated their ranks with children. In one documented case of press-ganging in June, government forces abducted children as young as 9 to serve in their ranks. Relief workers in Monrovia say the two major rebel groups are also forcibly recruiting children.

“It is clear that in the past several weeks, all sides have scrambled to give weapons to kids,” says Nils Kastberg, director of emergency programs at the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF. “We are talking about perhaps as many as 50 to 60 percent of the armed combatants being under 18.”

Some have been forced to fight, many recruited a second time after being demobilized in previous chapters of Liberia’s civil war, and aid workers say some have likely been lured by promises of food and water. Some 1.3 million people are trapped in stadiums, compounds, pinned down by deadly and unpredictable fighting, and unable to replenish dwindling supplies. In more than two weeks of fighting between rebels and President Charles Taylor’s forces in the capital, well over 1,000 people have been killed, the government says.

Preparing for armed kids

The first wave of peacekeepers — a Nigerian contingent deployed by ECOWAS, the Economic Community of Western African States — will be on the ground Monday, with logistical support from U.S. forces located off the coast of Liberia. Meanwhile, in Ghana, political negotiations are under way in an effort to plan for Liberia’s post-Taylor era.

These tasks are made even tougher by the large numbers of children and very young adults involved in the conflict.

“In terms of peacekeeping, it’s definitely a concern,” says Jo Becker, child rights advocacy director for U.S.-based Human Rights Watch. “We would advocate that forces should take care to minimize any harm to children, but the unfortunate aspect to international law is that once children pick up arms, they are legitimate targets.”

Most child soldiers have been press-ganged into service or joined voluntarily to avenge the deaths of family members, or to seek protection among rebel or government forces. They are used to find the way across mine fields, in dangerous spying missions, and pushed to the front lines where they die in disproportionate numbers. Girls are sometimes forced to fight, but more often are pressed into service as “wives” to provide sex on demand.

“These children are victims,” says UNICEF’S Kastberg. “The greatest crime is committed by the adults who allowed this to happen.”

But he notes, child fighters can be more volatile than adults, even if they are poorly trained. Immersed in military culture and violence throughout formative their years, child soldiers have been known to commit some of the most horrifying atrocities. In this conflict, as in others where children are used in battle, they are doped up — on amphetamines, marijuana and palm wine.

“There is nothing more terrifying that being stopped in the middle of the night at a checkpoint manned by 10-year-olds with guns,” says Kastberg, who has worked in international aid programs since for more than two decades. “Children haven’t had a chance to develop a value system. … They have no parameters. They are totally unpredictable.”

Managing the crisis

Many observers have been pressing for a plan to deal with young combatants to be put in place before peacekeepers’ arrival on the scene.

“An amnesty should be declared for all those under 18 and reception centers immediately established,” says Princeton Lyman, a senior fellow and Africa expert at the Council on Foreign Relations. “And there must be rules of engagement for how to deal with child soldiers who threaten force.”

There are precedents for the situation. Nigerian peacekeepers working in Sierra Leone, for instance, managed to isolate and disarm 5,000 to 7,000 child soldiers. In the Sudan, some 15,000 have been demobilized.

However, there is no universally accepted way to deal with under-aged combatants. Under international law, a child is considered no different than other combatants if he or she is armed, but their treatment raises moral questions.

And some experts suggest that a protocol as well as training troops for encounters with armed kids could save lives on all sides.

“If a soldier faces a child and ... it’s outside their realm of experience, there will be shock and hesitation, and that can cost a soldier his or her life, and perhaps that of a child,” says Rachel Stohl, a senior analyst at the Center for Defense Information.

She says studies suggest crowd dispersal techniques — such as firing into the air, using helicopters and bullhorns — could be used to convince many younger fighters to lay down arms and seek safe havens, which can be set up in advance.

UNICEF said it had been in Ghana negotiating with parties to the conflict to send child welfare workers into Monrovia alongside peacekeepers, to help separate child combatants and act as a deterrent for abuses against children by peacekeeping forces. These forces are typically not held to account for abuses that occur along the way.

Creating a future

Assuming successful intervention in Liberia, child soldiers still present a difficult long-term challenge.

The country is in shambles, and about one-third of Liberia’s total population is under 18 — people who have spent all of their formative years amid war and violence. Illiteracy runs about 80 percent. Unemployment is also about 80 percent.

“Ending the immediate hostilities will not end the destabilizing dimension of the Liberian environment,” warns Bismarck Myrick, a former ambassador to Liberia and now a lecturer in international affairs at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va.

Liberia will need to rebuild almost every aspect of its infrastructure, and its education system must be a top priority, he says.

Beyond a serious intervention to rebuild the education system, he says, the country badly needs a corps of psychiatrists or counselors to help people recover from the trauma of war and get reoriented.

“You disarm people, put them in school, you train them, give them vocational training … allow them to be positive contributors to society. You don’t just disarm them.”

In Liberia, a life of combat

That lesson has been learned the hard way in Liberia.

When Charles Taylor first won the presidency in 1997, after his forces finally ousted the government of Samuel Doe after seven years of fighting, there was a brief respite in the Liberian conflict and hope that Taylor would restore normalcy. During that phase of the civil war, some 50,000 children were killed and many more were injured, orphaned or abandoned, according to a State Department report. At the time, some of the estimated 20,000 child soldiers were disarmed and demobilized. But there was little done to reintegrate these kids into society. Nor was there much in the way of society to reintegrate them into.

The economy and infrastructure did not rebound under Taylor, who quickly established himself as just another corrupt and repressive dictator. It also emerged that he was the primary force behind rebel forces in neighboring Sierra Leone — and thousands of child soldiers there — who became infamous for hacking off the hands of villagers. As a result, Taylor’s government came under international sanctions, further deepening its economic hardship. Taylor is now charged with crimes against humanity in Sierra Leone, including the specific charge of recruiting children to fight.

Despite pressure from individual governments, UNICEF and some non-governmental organizations have continued working in Liberia, and were able to help a limited number of child soldiers. About 100 orphanages operated in and around Monrovia but many children still lived on the streets.

In the absence of good alternatives and lacking other experience, many Liberian child soldiers formed criminal gangs and mercenary groups who fought in regional conflicts.

The rebellion against Taylor started in 1999 and has culminated in the standoff at Monrovia. New conflict and extreme privation provide fertile ground for recruiting new and former child soldiers.

“Kids are used to recruit other kids,” says Stohl of the Center for Defense Information. “It’s a vicious, vicious cycle.”