About 30 men and a few women gathered quietly underneath the fury of the FDR Drive at rush hour, bundling up against the chill of the East River wind, awaiting their nightly sustenance: chunky chicken vegetable soup, a roll, a carton of milk and an orange. The soup varies, but the routine doesn’t change. Before Sept. 11 and since, these New Yorkers must scratch together a living on the slippery margins, overlooked and unwelcome, notwithstanding the reports of a more benign Big Apple since disaster struck the Twin Towers.

If anything, the tragedy at the World Trade Center twisted the screws on a populace that has found little comfort in the New York of the 21st century.

“I think there’s going to be more homeless, there’s no doubt about that,” said Thomas as he stood in line for his nightly feed, courtesy of the Coalition for the Homeless volunteers on the eastern fringes of 34th Street. “After what happened at the World Trade Center, the economy is going down. Where are people going to find jobs?”

Unlike the thousands of families who suffered a swift and unimaginable horror when their loved ones perished on Sept. 11, the personal stories of the homeless are filled with small tragic vignettes: tales of family breakups, abuse, unemployment after minimum-pay jobs fizzled out, mental illness, addiction, petty criminality.

One-two punch

Their plight receives little attention, although the swelling ranks of homeless will pose a stiff challenge to the city’s next mayor, business-tycoon-turned-politician Michael Bloomberg.

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, there were 29,802 people seeking sanctuary in the city’s shelter system in November — including around 12,000 children — up from 25,000 a year ago and topping the worst levels of the past 15 years.

“It’s been a one-two punch,” said Mary Brosnahan, the executive director of the coalition. “The severe recession plus 9-11 has left so many more people adrift.”

Unlike many New Yorkers, the coalition’s staff and volunteers will shed no tears when Mayor Rudolph Giuliani steps down from office on New Year’s Day.

A self-proclaimed thorn in the side of the city’s government, the coalition sparred with the city throughout the mayor’s administration over what it perceived as the neglect of the homeless.

Brosnahan noted the irony of the recent city advertisement campaign, chock full of celebrities, to woo visitors to the city. “The upper echelons of the Giuliani administration don’t want them to see the homeless.”

Because of a landmark legal victory for the coalition in 1981, New York has been obliged to provide shelter to all homeless New Yorkers.

But the form of shelter has been a subject of acrimonious debate, and a constant stream of court hearings as the coalition seeks to hold the government to what it sees as the letter and spirit of the law.

The numbers tell the story, as far as the advocacy group is concerned. In addition to the rising tide of homeless, Brosnahan explained that the average wait for permanent housing has become 11 months, up from five months before Giuliani took office.

“Giuliani acts like there is no problem,” said Nathaniel Thompson, one of the coalition staff members, who helps collect donations and distribute food. “He shows no compassion for the homeless.”

Homeless pitstops

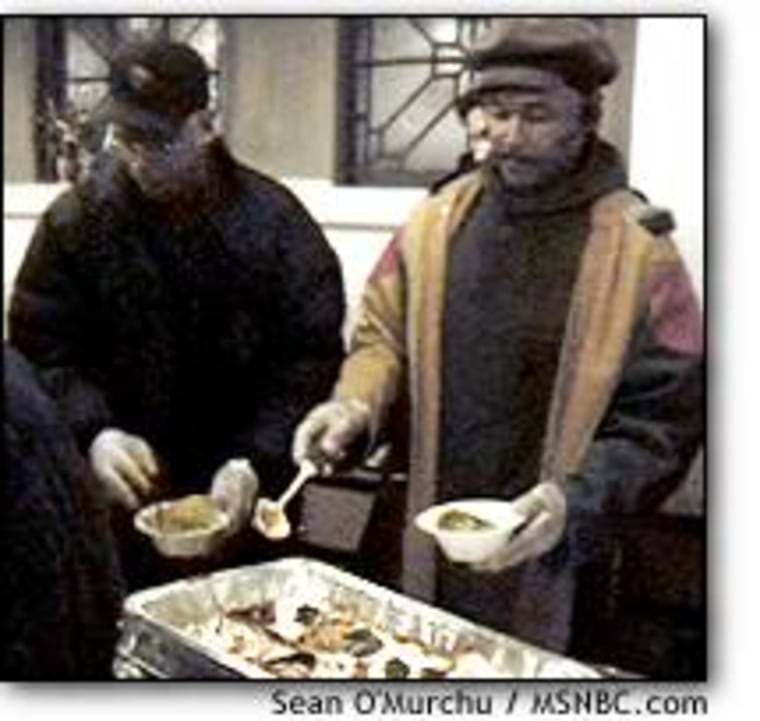

Meantime, Thompson and his team of volunteers conduct triage on the city’s needy every night, no matter the circumstances.

“We were out on Sept. 11,” said Thompson, who will help with what’s known as the Grand Central Food Program on Christmas Day.

Last Wednesday night, Thompson helped feed dozens of men and women in a room at the rear of St. Bart’s Church on Park Avenue and 51st Street.

Several men inquired when coats would be available, realizing that the unseasonably mild weather would inevitably give way to the paralyzing cold of a New York winter.

Thompson said that he would have coats the following night, but that he did have a large plastic bag full of knit hats and gloves to be distributed by the two vans that service the homeless pitstops around New York.

On Thursday, Thompson kept his promise, gathering a first installment of around 50 coats to distribute to the needy.

In addition to East 34th Street, the downtown van also feeds groups of hungry men and women who gathered in Center Street, which is near Federal Plaza, and at the Staten Island ferry terminal, on the tip of downtown Manhattan. (Another van stops at uptown locations)

The remaining food is dropped off at long-stay residences, or flophouses, around the Bowery.

In all, the coalition says that it serves more than 800 meals each night in New York.

Unchanged climate

James, who sleeps in a park near Center Street, appreciated the food and the contact, but he railed against police harassment.

And he expressed little hope that the Bloomberg administration would implement policies that would improve his life.

“He has so much money, he doesn’t even want to live in [Gracie] Mansion,” James said, referring to Bloomberg’s decision to stay put in his townhouse and not live in the official residence. “How can he know anything about the homeless?”

For many on the street, the changing faces at City Hall and the changed landscape in downtown Manhattan has little impact on the daily grind.

Although James, for his part, has noticed a softening in New Yorkers’ attitudes toward the homeless since Sept. 11.

“People come up and give me a dollar or two,” he said. “I think some kind of reality set it; they realized that it could be them on the streets.”

Others were less sanguine.

Thomas, who has been homeless for two years, said the result of Sept. 11 for him was stepped-up security, which makes it harder to find a place to hang out during the day, and to sleep at night. “Before [Sept. 11] happened, it wasn’t like that. Now security is everywhere you go, you feel uncomfortable. If it’s not a cop, it’s a detective or somebody else,” he said.

Many of the homeless opt to sleep anywhere but the often dangerous city shelters, a choice that marginalizes them further. By staying outside the city system, they cannot hope to qualify for more permanent housing.

“It’s very tough [and] a lot of people don’t want to be bothered,” said Marianne, who traveled from Coney Island with her husband, Joey, to collect food at the Staten Island terminal stop.

Joey found there were more people sleeping in the parks and subways since Sept. 11 and complained that it’s even harder to get work.

Their dream, they said, was to raise $200 and go to Florida. “People tell me it’s easier down there, and the weather is much better,” Joey said.

Lack of warmth

The travails of New York’s homeless have stumped more sympathetic city administrations before Giuliani’s — and will likely continue to do so in the years to come.

The Coalition for the Homeless believes that in the long run it would be cheaper to provide long-term housing for the homeless, rather than to pay for temporary accommodation and underwrite the ancillary services that have sprung up to cater for their needs.

But that argument has failed to move those who wield power.

Meantime, while Sept. 11 and its aftermath have stirred many New Yorkers to rededicate their commitment toward helping others, the impact on the homeless has been piecemeal in comparison to the energy, money and time expended on those who suffered directly in the tragedy.

Perhaps understandably, the reactions of many homeless are tinged with bitterness.

Charlie, a former inmate who grabbed a bite to eat at the Staten Island ferry terminal, said he and other homeless people are frowned upon more since the attacks.

“People say to us, ‘You’re homeless, you’ve been homeless, but now we’ve got to worry about this,” he said, referring to care of those who suffered after Sept. 11.

“Sure it’s a tragedy, but they are still living in warmth,” Charlie said. “They aren’t living in my park in Staten Island.”