Once the poster child for free-market economies in South America, Argentina has careened from one disaster to another over the past seven months. Now, with unemployment levels ballooning, social unrest spreading and the peso sinking like a stone, the international community — notably the United States — has taken a hands-off approach. Washington wants Argentina to sort out its own problems, no matter how bad it gets, according to analysts.

The embattled government of President Eduardo Duhalde has pegged its immediate survival to the International Monetary Fund, hoping the IMF will agree to roll over $9 billion in debt repayments due between now and 2003.

Failing that, the government may be unable to make a $500 million payment to the Inter-American Development Bank, due July 15.

Argentina’s problems don’t end there. What the Duhalde government is looking for is fresh funding from the IMF to stave off a growing crisis since the country devalued its currency this year.

But international lenders are gun-shy about helping a country that has defaulted on $140 billion in debt.

If Duhalde fails, “the expectation is that [he] will be hounded out of office, as he staked his future on getting an IMF package,” said Miguel Diaz, who directs the South America project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

On Sunday, Duhalde blamed the United States for his country’s problems. “I think the biggest difficulty we face is the ignorance and lack of concern toward our region of the government of the United States,” he told the Clarin newspaper.

“The North Americans do not consider themselves responsible and are prioritizing conflicts in other parts of the world in which the flow of oil to the West is at stake,” Duhalde said.

On Monday, IMF Managing Director Horst Koehler acknowledged progress in talks with Economy Minister Roberto Lavagna. “There has to come more, but there is progress,” Koehler told a meeting of the U.N. Economic and Social Council in New York.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, a frequent critic of Argentina in the past, also cited movement toward getting the nation “back on a good footing.”

THREAT OF VIOLENCE

Duhalde’s popularity has plummeted over the past few months. An opinion poll last week gave the Peronist Party leader a mere 8 percent popularity rating.

On June 27, police killed two protesters as demonstrators attempted to block major highways around the capital, Buenos Aires. With one in four Argentines out of a job, more protests are expected in the weeks ahead.

On Jan. 1, Duhalde became the fifth president in just over two weeks, after food riots left 27 people dead and shook the political foundations of one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries. But there is little enthusiasm for helping the career politician and former governor of Buenos Aires province. “What can [the United States] do, except to write a check for Duhalde?” said Mark Falcoff, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, who described Argentina’s strategy as a “game of chicken” with the IMF.

Moreover, Falcoff doesn’t see any compelling reason for the United States to rush to the rescue of Argentina, as Washington did in 1995 in the case of Mexico. “Mexico had a viable reform program. Argentina doesn’t,” he said.

Falcoff also noted that, unlike Mexico, an economic collapse in Argentina would be unlikely to affect the rest of the continent. “The only country that is likely to be affected is Uruguay,” he said.

DEMOCRACY IN PERIL?

However, Larry Birns, the director of the liberal Council on Hemispheric Affairs, asserted that the United States is short-sighted in its approach to Argentina.

“Democracy doesn’t have strong roots in the country. If democracy does not satisfy the expectations of the people, they are going to strongman rule,” he said. “And at that point, you may have a decisive intervention by the military.”

Birns also said the IMF and the United States must acknowledge some responsibility for Argentina’s economic collapse. “It’s now time for a repair job,” he said. “You don’t experiment with the destiny of a nation.”

Argentina’s embrace of the free market began with President Carlos Menem, who became the country’s second straight democratically elected president in 1989 after decades of military rule. He along with his Finance Minister Domingo Cavallo were hailed by the international business community for pushing business-friendly policies, aided by a currency board that linked the peso to the U.S. dollar.

In 1993, then-President Bill Clinton praised Menem as representing “a new generation of Latin American presidents committed to expanding freedom, strengthening democracy and creating prosperity. His leadership has been bold and his accomplishments truly impressive.”

Since stepping down in 1999, the flamboyant former president has been investigated about his links to the illegal sale of weapons to Croatia and Ecuador, as well as for taking bribes from Iran in exchange for covering up Tehran’s links to a 1994 bombing of a Jewish center in Buenos Aires.

UNHITCHED AND ALONE

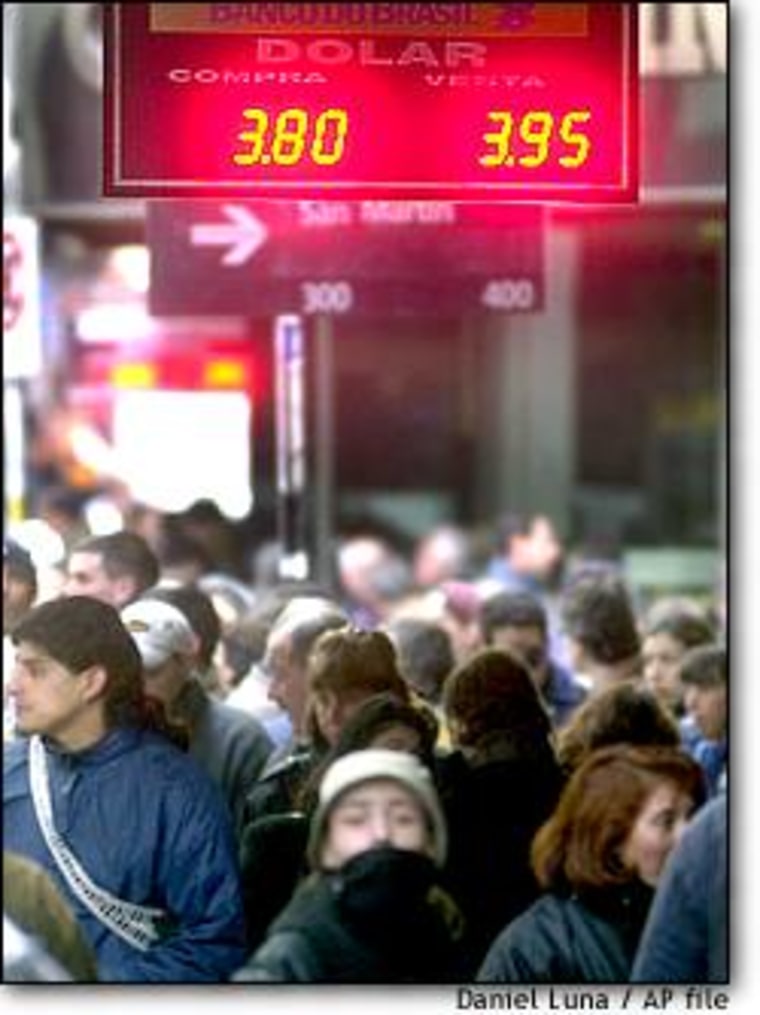

Meantime, in a bid to improve competitiveness, Argentina unhitched the peso from the greenback. It’s now valued at around 4 pesos to the dollar.

Ana I. Eiras, economic policy analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation, sees no danger of a military coup. Instead, she argues that the IMF and the United States should be wary of offering any more funds to the country, unless Argentina offers a plan for reform.

“Of course, Duhalde is going to ask for help from the IMF. At least, all the political leaders that I’m aware of want money from the IMF,” she said. “I think that the best way is not giving money without a plan. It’s very important that it’s a plan designed by the Argentines, not by the IMF.”

So far, Eiras noted, Argentina has failed to offer a credible proposal for tackling its myriad problems. Among them, she noted, are a convoluted regulatory system, a heavy tax burden and rampant corruption.

Carol Graham, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, noted “complete lack of clarity” from Argentina’s government on how it will reform the country, making it especially problematic for the world community.

She added, “What I find most worrisome is the extent they are willing to blame outsiders, to say it’s the IMF’s fault. It’s ultimately their problem. If you want outside help, the smartest way is not to bash the people you want to help you.”

(Sean Federico-O’Murchu is an international news producer/editor for MSNBC.com. Reuters contributed to this story.)