As leaders of the world’s wealthiest nations gather this week in Canada, they will ignore the poorest nation in the Western hemisphere. Haiti’s poverty levels hover near those of sub-Saharan Africa — and a two-year political stalemate has exacerbated the woes of the nation’s eight million people. But while the Group of Eight will discuss an Action Plan for Africa, Haiti is getting poorer while subject to a U.S.-orchestrated block on grants and loans to the country’s government until the impasse is resolved.

Last week, the Organization of American States reported that progress has been made in opening dialogue between the government of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide and the opposition, but the pace has been grindingly slow — and success is far from assured.

Meantime, the country — 600 miles off the coast of Florida — is sinking further into destitution, a flameout all the more notable given its proximity to the world’s wealthiest nation. On virtually any regional misery index imaginable, Haiti takes the prize.

According to UNICEF, the infant mortality rate stands at 81 per 1,000 births (compared with seven per 1,000 in the United States), less than half the population has access to safe water and just about a quarter has access to adequate sanitation.

The average income hovers around $1.40 a day and the life expectancy is about 53 years, a rate that international organizations fear could drop further as Haiti struggles with the highest level of HIV infection in the region — at more than 5 percent of the adult population.

“People are getting poorer and poorer because no investment can be made because of the political situation,” said Rafael Dessieu, president of the Methodist Church of Haiti.

A CONTENTIOUS ELECTION

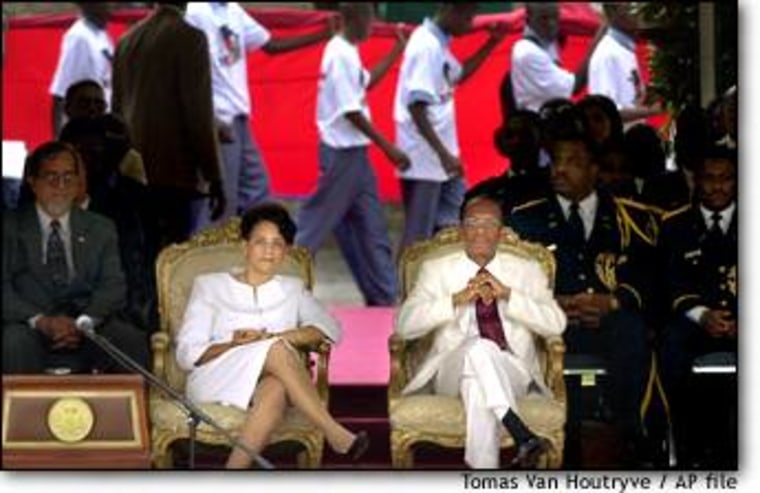

Haiti has been wracked by political turmoil throughout its existence. While Haitians celebrate the fact that the country was the first black republic in the world, Haiti only emerged from decades of dictatorship in 1990 when Aristide, the charismatic priest turned politician, was elected president — to be ousted seven months later in a military coup.

On Sept. 19, 1994, the United States led a U.N.-backed multinational force that was deployed in Haiti to secure the country and allow the return of Aristide a month later.

Ever since, Aristide has dominated the political landscape, stepping down in favor of an ally from the presidency in 1996 but winning re-election in 2000.

However, the vote was mostly boycotted by the opposition, upset by what was viewed as flawed legislative and local elections held earlier that year.

U.S. ROLE

The upshot has been political paralysis and economic deterioration, the latter worsened in the view of aid organizations by a U.S.-backed block on international loans and grants to the Aristide government.

According to a report in 2001 by Roberto Machado, an economist with the Inter-American Development Bank, the “major factor behind economic stagnation” is the withholding of such aid, which has been valued at $500 million. For its part, the United States has demanded steps by the Aristide government to remedy the 2000 election results and bring about political reforms before it will support the resumption of financial support. The United States does, however, fund non-governmental organizations (NGOs) operating in Haiti.

“There is no hiding our disappointment that, nearly eight years since the restoration of elected government, Haiti has made so little progress,” Lino Gutierrez, deputy assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, said last month.

Washington’s policy is supported by the Convérgence Démocratique, a loose confederation of opposition parties — including some backers of former dictator Jean Claude Duvalier — that protested the flawed election process.

But it’s a stance that infuriates humanitarian groups. “What about the fact we [the United States] poured millions and millions into the country when there were dictators killing people — and we did nothing,” said Rita Russo of the Saint Boniface Haiti Foundation, which runs a hospital in Fond des Blancs, Haiti.

However, the United States has its defenders. Stephen Johnson, a Latin America policy analyst with the Heritage Foundation, a Washington-based conservative think-tank, said there was little sense in directly funding a government “that has had a deplorable record in using those resources.”

Instead, the United States should continue to help the NGOs on the ground in Haiti, especially in the area of education, he said.

SLOW DIPLOMACY

The stutter-step push to resolve the crisis has been left to the Organization of American States (OAS) in association with the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM).

It has led to innumerable mediation missions, and last week, the OAS’s Assistant Secretary General Luigi Einaudi said the stage may be set for resolving the deadlock.

Haiti’s Permanent Representative to the OAS, Ambassador Raymond Valcin, also saw signs of progress, noting the government had taken steps to re-open lines of communication with the opposition. But he objected to making agreement with the opposition a condition for international financial assistance.

Those on the ground in Haiti are not as optimistic. “[The two sides] are playing the cat-and-mouse game,” said the Methodist Church’s Dessieu. “They forget that negotiations mean giving up something. Instead, they are thinking about their own power, rather than the millions who are suffering because of their ambitions.”

QUALITY OF THE OPPOSITION

Another problem, according to analysts, is the quality of the forces lined up against Aristide and his party, Fanmi Lavalas (Lavalas Family).

“Some are very well rooted and relatively sincere, the rest are a bunch of yobbos whose only raison d’être is to oppose any agreement,” noted one observer, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The left-leaning Council on Hemispheric Affairs was scathing in a report earlier this month. “Due to the members’ close working relationship with Washington, the Convérgence’s directors are, in effect, co-rulers of the country, in spite of their lack of a popular base of supporters.”

Brian Corcoran, an American lawyer based in Haiti who works for the government to prosecute human rights abuses, believes the opposition has little reason to seek a resolution. “There is an inverse relationship between electoral support and [U.S. government] support for the Convérgence Démocratique,” he said.

“The international community has missed an opportunity [to help the democratic process],” said Corcoran, who has worked in Haiti since 1996. “Because the international community was opposed to Aristide, they promoted people whose only platform was opposing Aristide. There is a lot of room for an opposition that could have challenged the Lavalas Party on policies,” he said.

VIOLENCE INCREASE

In the meantime, the economic decay has been accompanied by widespread lawlessness and an increase in street violence, including brutal and deadly attacks on opposition supporters and even journalists.

In December, an apparent coup attempt was met with attacks on buildings associated with opposition parties and leaders. Human rights organizations expressed alarm about the apparent free rein given to armed “popular organizations” loyal to Aristide.

A scorecard issued February by the National Coalition for Haitian Rights painted a dismal picture, noting for example that nearly 20 journalists have been forced to flee for safety in other countries since 1994.

The organization’s executive director Dina Paul Parkes told MSNBC.com, “I think you have a weird dynamic in Haiti right now, you have the general disintegration in some areas, but the country has progressed in the past 10 years.

“You cannot go back to a dictatorship, it has moved too far to slide back to that. Now there is a human rights infrastructure, there is a journalists’ association. Those signs of a nascent democracy are there and it would be hard to snuff them out.”

DAY-TO-DAY MISERY

But little gains has been made in easing the impoverished existence of ordinary Haitians, despite the best efforts of NGOs operating in Haiti.

One reason may be that the government is distracted from development issues by the political crisis, said Rodney Phillips, the UNICEF country representative in Haiti. “I have been here for two years now, and I have begun to see recently the real face of poverty on the street of Port-au-Prince and rural areas.”

He noted more and younger street children, child prostitution, a surge in street crime by armed unemployed youths. “The whole security situation has clearly got worse.”

Then there’s the unique Haitian tradition of Restavék, whereby poor families send children as young as five years old to work for families in the cities and they end up “in virtual slavery,” Phillips said.

The Methodist Church’s Dessieu said Haitians are losing hope; those who can flee, while most scratch a living in increasingly desperate circumstances.

“One thing that you can read on the faces of everybody is that they are tired of the situation,” he said.

(Sean Federico-O’Murchu is an international news producer/editor for MSNBC.com)