Negotiators and diplomats were working Thursday on a scaled-back version of a global climate change treaty that could be agreed by next month's deadline, without firm U.S. commitments.

The idea of forging a political agreement, instead of a legally binding treaty, was becoming a more accepted possibility as negotiators acknowledged some nations, including the United States, would not be ready in time for the December U.N. climate conference in Copenhagen, Denmark.

"People are more and more talking about a framework, a framework that you clarify further in the following months," said Artur Runge-Metzger, chief delegate from the EU Commission.

European officials said they envisioned a political accord emerging from Copenhagen enshrining plans by developed countries to cut carbon emissions and by emerging economies to trim back the growth of their emissions. It also would include specific numbers on how much money wealthy countries would channel to the poor to combat the effects of climate change.

Such a political deal would not be legally binding, but would carry the authority of world leaders who would come to the Danish capital to sign off on it. Negotiations would continue for several months and possibly one year until a legally binding treaty was ready, the officials said on condition of anonymity, due to the sensitivity of the ongoing talks.

"We as the EU will certainly push and push and push to get a real legal outcome," Runge-Metzger said, adding that the Copenhagen agreement should "definitely ... have a timetable" for negotiating a full treaty.

Even an interim deal would clear the way to mobilize funds to help poor countries. The EU has said $7.4 billion to $10.4 billion will be needed over the next three years for developing nations to begin planning their first steps toward controlling their emissions and protecting themselves against the effects of climate change.

'Morally binding' if nothing else

Yvo de Boer, the top U.N. climate official who oversees the negotiations, said any decision emerging from Copenhagen that is accepted by all 192 countries would be "morally binding" even without formal legal status.

The United States — the only industrialized nation to reject previous climate deals — had pledged to be a leader in climate change policy after President Barack Obama took office. U.S. climate legislation was bogged down this week, however, as a group of conservative Republican senators demanded more cost-analysis of the bill, which calls for cutting greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and factories by 83 percent by 2050. On Thursday, Democrats on the panel approved the legislation with no Republicans present, and it will now be merged with bills being written by five other Senate panels for a vote by the full Senate. The House has already passed a climate bill.

"This cannot be an excuse for the world not to get an answer to the climate problem," said Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt, whose country holds the rotating EU presidency.

"We need a strong agreement that puts together all the efforts that all the countries — both developed and developing — are ready to put on the table," Reinfeldt said Thursday while visiting India. "I hope to see world leaders come to Copenhagen to make the handshake."

Nations had hoped to conclude a new climate treaty at Copenhagen to succeed the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which called on 37 industrial countries to reduce emissions of heat-raising gases by an average 5 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. The U.S. rejected it because it made no demands on major developing countries like India and China.

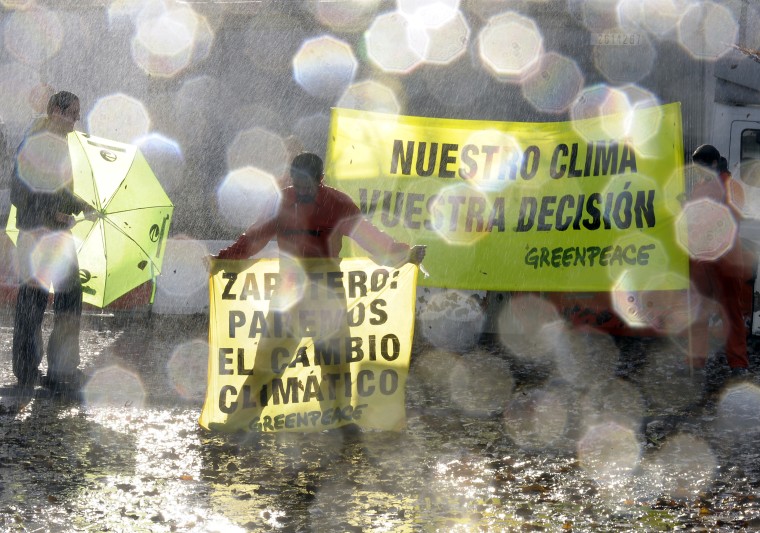

At the U.N. talks in Spain, lobby groups and delegations were showing frustration with the scaling back of ambitions.

"We are completely dismayed by the shuffling of feet and sliding backward of the developed countries," said Raman Mehta, program manager in India for global anti-poverty agency ActionAid.

Negotiators now are considering ways of including the Americans in the Copenhagen pact without requiring immediate U.S. pledges for emissions reduction targets or for contribution to a climate aid fund to help developing countries cope with the effects of climate change.

The success of Copenhagen now "depends very much on President Obama himself, on ... whether he can put numbers on the table or not," said the European Union delegation chief, Runge-Metzger.

Alden Meyer, policy director at the Washington-based Union of Concerned Scientists, said the U.S. would have to make its case at Copenhagen for an extension. "It comes down to trust. How much can the U.S. be trusted to deliver, particularly given the Kyoto experience," he said.

Scientists say industrial countries should reduce emissions by 25 to 40 percent from 1990 levels by 2020, but targets announced so far amount to far less than the minimum.

Legislation working its way through Congress would reduce U.S. emissions by about 4 percent below 1990 levels. While the Europeans and developing countries have complained about the Washington's "low ambitions," most accept it cannot be changed.

Britain's Climate Change Secretary Ed Miliband said that, despite mounting pessimism, he is still hopeful of reaching a treaty at the Dec. 7-18 Copenhagen conference. Miliband told UK lawmakers in London on Thursday that countries "shouldn't be in Plan B territory," but acknowledged a deal is more likely to be brokered in 2010.

"Achieving a full legal treaty, given the pace of the negotiations, is unlikely," Miliband said, adding that he is disappointed with the prospect of a watered-down version at the Copenhagen talks. "I think an agreement without numbers is not a great agreement. In fact it's a wholly inadequate agreement."

The U.N. chief also urged action, calling climate change "the leading geopolitical and economic issue of this century."

"From the moment I took office as secretary general, I have urged leaders of the world to make climate change a top priority," Ban Ki-moon said in Athens on Thursday. "There is no doubt that the Copenhagen negotiations are complex. ... However, our objectives are clear. We must reduce greenhouse gas emissions that are causing climate change."