In America, you get what you pay for. Those who pay more get better service. That's the way it is in restaurants, and in health care, too.

But imagine a restaurant with one kitchen, one chef, but two doors and two price lists. That's the model of health care that some doctors are practicing.

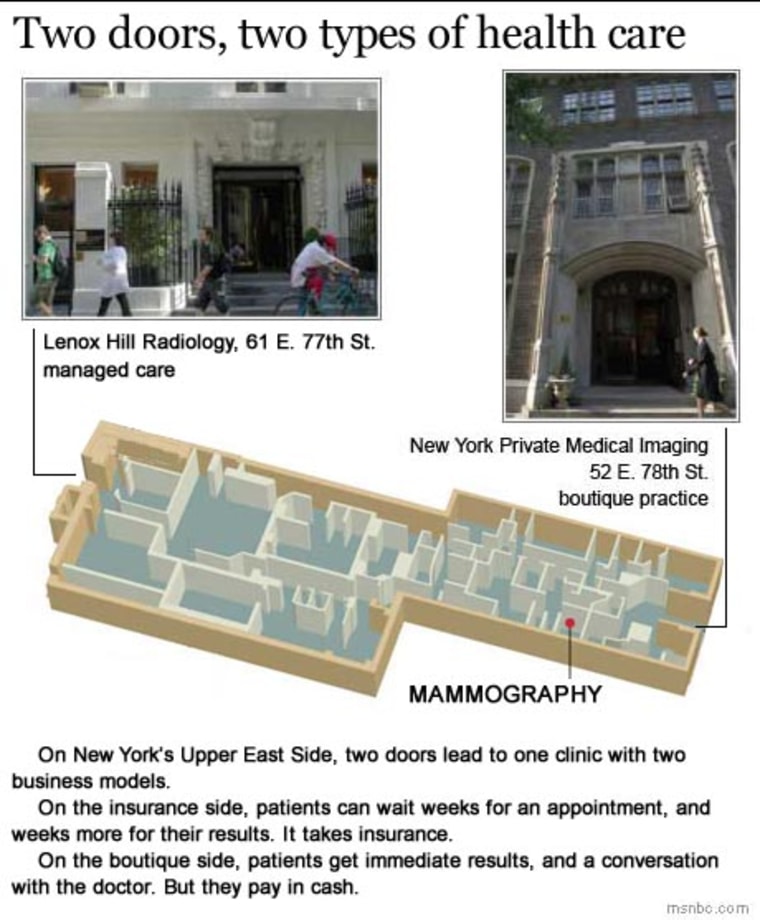

In New York City, msnbc.com heard of doctors locating their practices on corners, so they can have one door where they take insurance and another door offering services for patients who pay cash up front for each procedure.

We visited one of these clinics with two doors, to see how it works. The result is a glimpse into a two-tiered system of health care, a system that could be coming to a street corner near you.

On Manhattan's fashionable Upper East Side, the door on 77th Street says Lenox Hill Radiology. It's a busy place, with 20 or 30 people typically waiting in chairs. It takes insurance.

But if you walk a few steps down the block to Madison Avenue, and one block up to 78th Street, you'll walk through the door of New York Private Medical Imaging. The waiting room has only four chairs, usually empty. It takes cash, checks and credit cards. You can try to recoup some of your money later if you have insurance.

Both doors ultimately lead to the same area of changing rooms and scanning equipment. The same technicians perform PET scans and MRIs on the same machines. The employees are warned, in a written policy, not to tell the patients about the other door.

As Congress spars over how to fix the nation's health care system, we've seen more doctors reject the managed care dominated by insurance companies, pushing patients to pay $1,500 to $2,000 a year for “concierge” service with more of the doctor's time and attention. (Read the companion article: Patients face bitter choice: Pay up or lose care.)

At least those patients know what they're choosing.

But another group of doctors has set up their own segregated system, taking insurance from patients who come through one door, while collecting higher fees from patients who can afford to pay up front.

A testTo see how it works, msnbc.com sent two reporters, Linda Carroll and Helen Popkin, for their routine mammograms on the same afternoon to document their experiences. And later we returned to interview doctors on both sides.

The purpose: to determine if both women received the same care. And if there were any differences, were they meaningful or superficial?

At the Lenox Hill clinic, on the insurance side, Helen waited 15 days to get an appointment. On the day of her mammogram, she stood in line at the reception desk in a crowded waiting room. An elderly patient wandered the reception area in her hospital gown, pleading for someone to help her. In the changing room, Helen's gown was the usual thin seersucker. The technician was friendly and efficient, though Helen didn't see a doctor. She went home not knowing whether she was healthy or not, and waited nine days for her results. But it was good news, a clean bill of health. Though the list price was $350, Helen's insurance paid the clinic $140 and she paid nothing, because her health insurance covers preventive care such as mammography.

At the Private Imaging clinic — the boutique side — Linda was able to get an appointment in two days. She was greeted immediately in the private reception area. She changed into a comfy spa robe. Her technician was also friendly and efficient, then the doctor read the scan after a few minutes, reassuring her, “Your mammogram's negative. Nothing to worry about. See you next year.” Linda walked out carrying a copy of her X-rays. Linda wrote a check to the clinic for $350; if she'd had the same insurance plan as Helen, Linda's net cost would have been $210.

How it got to be this wayDr. Carmel Donovan used to be on the insurance side of this setup, at Lenox Hill Radiology. Her husband and son still manage both sides. Eight years ago she put in the second door and a separate reception desk, incorporating as New York Private Medical Imaging.

The first factor that drove her out of managed care, Donovan explains in her Irish accent, was the declining rate of insurance payments. “It costs $100 to do a mammogram, but reimbursement was down to $50. Then it went down to $29 for a chest X-ray for a child. Impossible!”

The second factor, she said, was time — time to talk with patients and their doctors, time to read the scan with care.

“On the managed care side, it was just — you couldn't talk to people, because you have to produce!” Donovan said.

“You see, they see over 500 patients a day. And you have this pressure. You have to just get stuff right out. You see, it's impersonal.”

Talking with patients allows her to explain what she found, or to reassure them that she found nothing. And she says that conversation can help her with a diagnosis. Say a child comes in with a possible fracture of an arm, but from the X-ray it's not clear.

“So I come in, I put my hand on there, and if they jump, I know that there's a fracture.”

She said that even the parts of her practice that appear superficial, the robe and private waiting room, contribute to better health care. She tries not to have the patients wait long, “because that's anxiety producing.”

The rescanAlthough the actual mammogram itself seemed identical for Helen and Linda, there was one subtle difference.

After a quick quality check on Helen's scans, on the insurance side, the technician said the pictures were sharp, and sent her on her way.

The technician did the same with Linda, the boutique patient, and also said the scans were sharp.

But when Linda's radiologist examined Linda's X-rays a few minutes later, she said one of them was blurry, and sent the technician back to repeat it.

That couldn't have happened on the insurance side. By the time Helen's radiologist looked at her X-ray, days later, Helen would be long gone. If the radiologist thought one of her scans was blurry, the doctor would either have had to rely on the information at hand or call her back for another appointment.

35 secondsA few minutes after Linda's mammogram on the boutique side, a radiologist, Dr. Mona Darwish,knocked and walked into the changing room.

“Hi, I'm Dr. Darwish, how are you?” she said cheerfully. “Your mammogram's negative, OK, so nothing to worry about.”

Linda asked a couple of questions about a previous mammogram, and the doctor reassured her again. The conversation went back and forth. They laughed together, the tension broken.

“See you next year,” Darwish said.

The entire conversation took 35 seconds.

That personal contact was not available to Helen or the other patients on the insurance side.

All Helen heard was the technician's rushed dismissal, “OK, your doctor will get the results in seven to 10 days.”

As it turned out, while Darwish is on the staff of the insurance side of the clinic, she reads the mammograms for patients on both the insurance and boutique sides.

So, although our two patients went through separate doors, they had their scans read by the same radiologist.

But only Linda, the boutique patient, got to meet the doctor and get an immediate result.

If Linda's mammogram had shown something unusual, Donovan said, Darwish would have spent a lot more than 35 seconds with her. But first the doctor would have called Linda's primary care physician to discuss who would deliver what information.

On the insurance side, when Helen's doctor got her results nine days later, it was only a written summary, not copies of the scans. Helen said a previous mammogram had left her with questions, but she didn't get a chance to ask those questions this time around.

Meeting the patients digitallyOne of the 20 radiologists on the insurance side at Lenox Hill, Dr. Marc Liebeskind, said he and his colleagues offer equally good health care as the boutique side, although they don't meet most of their patients.

“I''m meeting most of my patients digitally,” he said.

Instead, Liebeskind reads scans in a tiny office of computer monitors.

“I read all day long. I read from morning to night. We do close to 125,000 cases in this facility each year. The more the managed-care reimbursements drop, the more we have to do.” That works out to 80 to 100 scans a day for him.

Comparing his work with Donovan's, he said, “The quality of care is identical. The equipment is identical. The technology is identical. It's not a matter of quality, so much as it is a matter of luxury. It's the patient experience that's different. I think the quality is identical.”

Scientific studies back up his view that a doctor who reads more scans can be more accurate. Doctors identify more cancers, and are less likely to think healthy tissue was a cancer, when they have more years of experience and examine more scans per year.

But would his work improve if he also took a few minutes to examine the patient, if he had that 35-second or longer conversation?

“Radiologists are like umpires,” Liebeskind said. “We try to be relatively neutral. In some ways, the less you personalize the patient, the more objective your opinion, the better the quality.”

All in all, he said, “Dr. Donovan has the luxury of practicing in a way that very few doctors get to practice these days. Managed care is the reality.”

The trend

A written policy given to employees at the clinic forbids them from discussing the other side. If patients were referred to Lenox Hill because it takes a certain insurance coverage, and then those patients ended up on the other side, paying more for care at Private Imaging, the business would be open to allegations of fraud, the policy says. Steering of patients to a more profitable service would violate the clinic's contracts with insurance companies.

Donovan said patients learn of her boutique service from other doctors, often boutique physicians themselves. She said she knows of other doctors in New York City who have two doors, one for managed care and the other for boutique patients.

Dr. Ralph Lopez, an adolescent health specialist and the president of the Independent Doctors of New York, said he knew of more hybrid offices opening, but his group urges its members to pick one style of practice or another, lest they be accused of steering. His association of independent doctors — of which Donovan is a member — grows about 10 percent each year.

“This isn't about making more money.” Lopez said. “This is about being an independent doctor who could make choices about how I'm going to treat my patients.

“This is a noble profession, and I love the idea that I am working for my patients and for my patient's behalf,” Lopez said. “I can choose where I want to send the patient. It's my choice. I don't need to get approval.”

An ethical diagnosisBioethicist Art Caplan, an msnbc.com contributor, said that even the relatively subtle differences in the experiences of the two patients are unsettling.

While boutique and concierge care have been sold to patients for their benefits to those who pay extra, Caplan said, they have eroded the care that other patients receive, particularly the ability to get the doctor's ear for a few minutes.

“I was bitterly disappointed and disturbed by what you found,” said Caplan, director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. (You can read a full commentary from Caplan here.)

“If you have to have a system where you need to bribe your way with the doctor to get a few minutes of conversation or a retake of your screening examination because they may not be satisfied with the way it came out, that's a very broken health care system.

“What is happening with concierge medicine,” Caplan said, “based on what you discovered, is that we're biting into the quality of care if you're not paying a premium. That's unethical. It's immoral. It's just flat-out wrong.”