The world's largest atom smasher broke the world record for proton acceleration on Monday, firing particle beams with 20 percent more power than the American lab that previously held the record.

The power of the Large Hadron Collider's proton beams is essential to the project's ultimate goal: smashing particles into each other with enough force to shatter them into the smallest building blocks of matter.

The early-morning test continues a recent sequence of successes that have elated scientists who were disappointed by the $10 billion machine's collapse last year just after its startup in a 17-mile tunnel under the Swiss-French border. The breakdown required extensive repairs and improvements.

The collider fired two particle beams at 1.18 trillion electron volts early Monday, surpassing the previous high of 0.98 TeV held by the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois since 2001, according to the European Organization for Nuclear Research. The organization is better known by the French acronym CERN.

Physicists measure the energy of the hair's-width beams, not their speed, because the protons are already traveling close to the speed of light and cannot go much faster.

One proton at 1 TeV is about the energy of the motion of a flying mosquito. When a beam is fully packed with 300 trillion protons with 7 TeV energy — the goal of the LHC — it is like an aircraft carrier traveling at 20 knots. That is why the scientists are carefully learning how to run it and make sure all protection systems are working, said CERN spokesman James Gillies.

More significant advances are expected during the first half of next year when the LHC plans to raise each beam to 3.5 TeV in preparation for experiments create conditions like those 1 trillionth to 2 trillionths of a second after the big bang.

Physicists hope that will help them understand suspected phenomena such as dark matter, antimatter and supersymmetry and, ultimately, the creation of the universe billions of years ago.

CERN Director-General Rolf Heuer said the early advances have been "fantastic."

"However, we are continuing to take it step by step, and there is still a lot to do before we start physics in 2010," he said. "I'm keeping my champagne on ice until then."

It may take several years before the LHC will in theory be able to detect the elusive Higgs boson, the particle or field believed to give mass to other particles. The discovery would rank among the greatest in physics.

Physicists have used smaller, room-temperature colliders for decades to study the atom. They once thought protons and neutrons were the smallest components of the atom's nucleus, but the colliders showed that they are made of quarks and gluons and that there are other forces and particles.

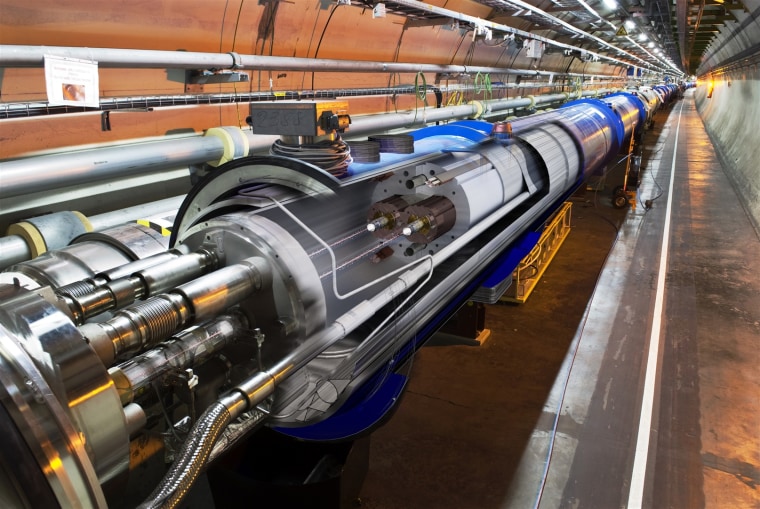

The LHC operates at a temperature of nearly absolute zero, colder than outer space. That operating temperature enables the collider ring's 2,000 superconducting magnets to guide the protons most efficiently.

More than 8,000 physicists from labs around the world have work planned for the Large Hadron Collider. The organization is run by its 20 European member nations, with support from other countries, including observers from Japan, India, Russia and the United States, which have made big contributions.