The scent of a single chemical can turn peaceful, happy fruit flies into flying fists of fury.

For the first time, scientists have found a rage-inducing pheromone and the neuron that detects it in fruit flies. The research, detailed in the journal Nature, could help explain everything from bar fights to species-wide population control.

"Not only did we identify the pheromone that leads to aggression and its neuron," said David Anderson, a scientist at Cal Tech and co-author of the Nature study, "but we were able to manipulate the ability of the flies to increase aggression."

For the most part, fruit flies are a peaceful species. Give a group of flies a piece of food, and they graze peacefully. Give them some land, and they usually share the territory without incident.

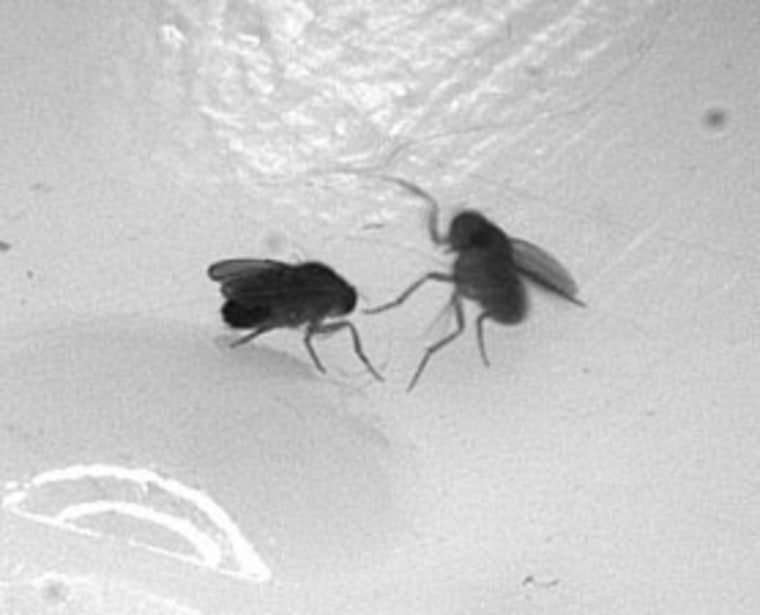

These idyllic scenes, however, can quickly turn violent. Drop filter paper soaked in artificially produced pheromone, known as 11-cis-vaccenylacetate, into the air around six flies, and they quickly start karate chopping and judo wrestling their opponents, rearing up on their hind legs and snapping down violently, and grappling with their forelegs.

Eventually one fly dominates, scaring all other flies away.

Natural CVA, found in the hard exoskeletons of flies and theoretically released when the flies bump against each other, also enrages flies. Anderson and colleagues crammed up to 100 fruit flies into a container with tiny holes on the top and watched as the flies fought, releasing ever greater amounts of CVA.

The CVA rose through the container and out of the holes on top, where two other flies were waiting. The two flies on top had plenty of food and plenty of space. However, when they smelled the CVA produced by the fighting flies under them, the two flies on top started fighting as well.

When scientists remove the flies from inside the lower container, the two flies on top become peaceful again.

Fruit flies are tiny — about 2 millimeters long on average — and like Bruce Lee, their fists are fast. However, not fast enough to escape the notice of special cameras and software that tracked punch, block and hold the flies used on each other.

The scientists used their equipment to measure aggression in the flies by counting each blow. When CVA was present, the number of aggressive rearing and lunging jumps was more than five times normal levels.

After identifying the pheromone, the scientists set out to find the part of the fly's antennae, the receptor, that binds to CVA. They removed five genes that encode for specific receptors in fruit flies.

These genetically modified flies were unable to smell CVA, and no amount of the CVA could trigger aggressive behavior.

Other scientists had previously identified CVA as an aggression promoting pheromone. Other researchers had even identified the neuron that detects CVA. Anderson's new work links the pheromone with the neuron in the flies antennae and the genes that produce those neurons.

However, humans that smell CVA don't fly into a rage. "This evolved as a private means of communications between fruit flies," said Anderson.

This pheromone is a way to keep fly populations in check. When the number of flies becomes too large, some flies decide to forgo the fighting and find another food source.

Although Anderson and his colleagues were able to isolate the chemical that produces aggression in flies, what about humans?

"Aggression pheromones are used not only insects but in mammals as well," said Anderson. "But whether we use aggression-promoting pheromones is speculation."

"This is the most direct link between pheromone and anger," said Leslie Vosshall, a scientist at Rockefeller University in New York. Vosshall agrees that there could be such a chemical.

"Most of what turns out to be true in animals turns out to be true in humans as well," said Vosshall.

A single chemical probably won't turn happy people into instant rageaholics thoughts; our brains are too developed to react to a single pheromone that strongly.

However, if discovered, an anger-inducing pheromone could make humans as violent as, in this case, fruit flies.