Hundreds of communities far from congested highways and belching smokestacks could soon join America's big cities and industrial corridors in violation of stricter limits on lung-damaging smog proposed Thursday by the Obama administration.

Costs of compliance could be up to $90 billion, but the government said the rules would save lives and up to $100 billion in hospital visits as well as missed work and school days.

Following a review of Bush-era rules, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed what it called "the strictest health standards to date for smog." The American Lung Association and other activists praised the move, but the oil industry called it a politicization of the scientific process.

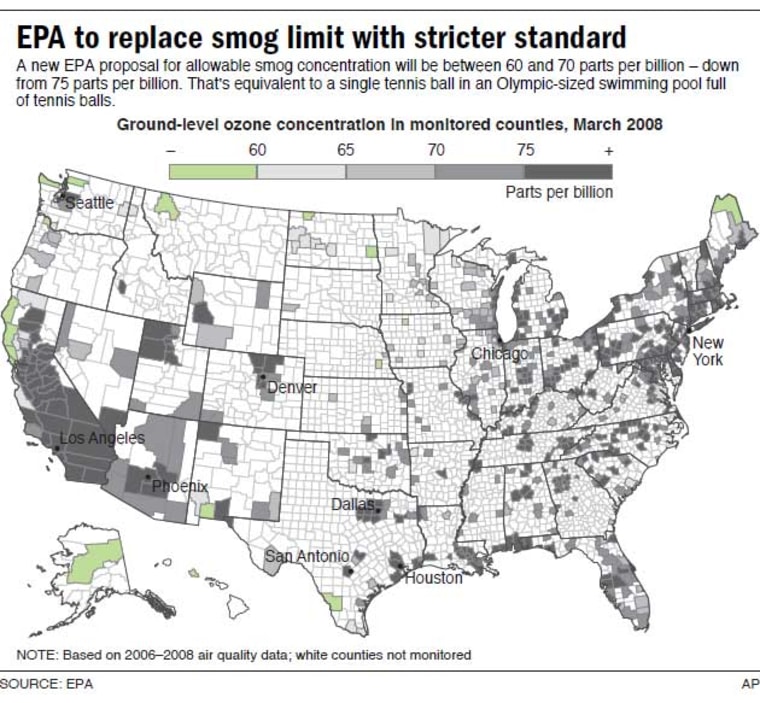

More than 300 counties — mainly in southern California, the Northeast and Gulf Coast — already violate the current, looser requirements adopted two years ago by the Bush administration and will find it even harder to reduce smog-forming pollution enough to comply with the law.

The new limits could also more than double the number of counties in violation and reach places like California's wine country in Napa Valley and rural Trego County, Kan., and its 3,000 residents.

For the first time, counties in Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, the Dakotas, Kansas, Minnesota and Iowa might be forced to find ways to clamp down on smog-forming emissions from industry and automobiles, or face government sanctions, most likely the loss of federal highway dollars.

In a slap at the rules set in by the Bush administration, the Obama EPA stated that "the agency is proposing to replace the standards set by the previous administration, which many believe were not protective enough of human health."

Former President George W. Bush personally intervened in the issue after hearing complaints from electric utilities and other affected industries. His EPA set a standard of .075 parts per million, stricter than one adopted in 1997 but not as strict as what scientists working for the EPA said was needed to protect public health.

"Using the best science to strengthen these standards is a long overdue action that will help millions of Americans breathe easier and live healthier," EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said in a statement.

The Obama EPA proposed a standard at a level somewhere between .06 and .07 parts per million measured over eight hours — the same that was proposed by the EPA science panel. EPA will select a specific figure within that range later this year.

"Depending on the level of the final standard, the proposal would yield health benefits between $13 billion and $100 billion," the Obama EPA stated. "This proposal would help reduce premature deaths, aggravated asthma, bronchitis cases, hospital and emergency room visits and days when people miss work or school because of ozone-related symptoms. Estimated costs of implementing this proposal range from $19 billion to $90 billion."

The EPA will take public comment for 60 days, as well as hold three public hearings, before making a final decision.

Activists for, industry againstRepresentatives of the oil and gas industry, which said they have already invested $175 billion toward environmental improvements, were quick to say the proposal lacked "scientific justification."

"There is absolutely no basis for EPA to propose changing the ozone standards promulgated by the EPA administrator in 2008," the American Petroleum Institute said in a statement. "To do so is an obvious politicization of the air quality standard setting process that could mean unnecessary energy cost increases, job losses and less domestic oil and natural gas development and energy security."

The American Lung Association had the opposite view. "EPA is following the overwhelming evidence that our nation needs a stronger ozone standard," ALA President Charles Connor said in a statement. "EPA owes this protection to the millions who live where ozone smog sends children to the emergency room and shortens the lives of people with chronic lung disease."

Parts of the country that have already spent decades and millions of dollars fighting smog and are still struggling to meet existing thresholds questioned what more they could do. They've already cut pollution from the easier sources, by increasing monitoring and enforcement and requiring car emissions tests.

"This EPA decision provides the illusion of greater protectiveness, but with no regard for cost, in terms of dollars or in terms of the freedoms that Americans are accustomed to," said Bryan W. Shaw, chairman of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Texas, with its heavy industry, is home to Houston, one of the smoggiest cities in the nation.

The new regulations would mean more controls on large industrial facilities, plus regulating smaller facilities and sources. New federal regulations in the works to improve car and truck fuel economy and curb global warming pollution at large factories will also help communities meet any new standards, the EPA said.

Some parts of the country that could be found in violation of the proposed standards have very few cars and little industry. In places like these, smog-forming pollution is being blown in from hundreds of miles away.

Charlene Neish, director of Trego County Economic Development, moved to the rural county in western Kansas a decade ago from Phoenix to escape big city problems like traffic and air pollution. Neish was shocked that her county, which has about nine people per square mile and virtually no industry, made the list.

"There is absolutely nothing in Trego County," Neish said. "We have wide open spaces and fresh air."

In Utah, six more counties would join the three in violation of the Bush standard.

Cheryl Heying, director of Utah's Division of Air Quality, said the change will not only require additional reductions in vehicle and industrial emissions, but a regional focus on other contributors such as wildfire smoke and offshore shipping.

"That doesn't mean we're just going to point our finger at everyone else, but if we don't cooperate, we're never going to get it done," Heying said.

The controversy dates back to April 2008 when, in a stern letter to then EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson, an EPA advisory panel of scientists expressed frustration that their unanimous recommendation for a more stringent standard was rejected by Johnson.

Johnson lowered the amount of ozone that should be allowed in the air for it to be considered healthy from .08 ppm to .075 ppm. That meant 345 additional counties nationwide are in violation of the federal air quality standards for ozone, commonly known as smog, and must find ways to reduce the pollution.

Some chronic polluters are far above the old limit of .08 ppm — Los Angeles County and a large swatch of southern California, for example, and a long stretch from Washington, D.C., up to New England on the East Coast.

The Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, created by Congress to advise the EPA, had urged the EPA to set a standard for ozone of between .06 and .07 ppm.

In its letter to Johnson, the committee said it remained convinced that the EPA's concentration level "fails to ... ensure an adequate margin of safety" for the elderly, children and people with respiratory illnesses.

Johnson said he took those recommendations into account, but disagreed with the scientists. "In the end it is a judgment. I followed my obligation. I followed the law. I adhered to the science," Johnson said in a conference call with reporters.

The EPA has said, based on various studies, that cutting smog from .08 to .075 ppm would prevent between 900 and 1,100 premature deaths a year and mean 1,400 fewer nonfatal heart attacks and 5,600 fewer hospital or emergency room visits. A separate study suggests that tightening the standard to .07 ppm could avoid as many as 3,800 premature deaths nationwide.

Johnson said he did not consider the cost of meeting the new air standard. The federal Clean Air Act requires that health standards for ozone and a handful of other air pollutants not take costs into account.

The Bush-era EPA estimated that compliance with a smog standard of .075 ppm would cost $7.6 billion to $8.5 billion a year and "yield health benefits valued between $2 billion and $19 billion."

The Obama administration last year had indicated it planned to scrap the Bush smog limits, when it asked a federal judge to stay a lawsuit challenging the March 2008 standards brought by 11 states and environmental groups.