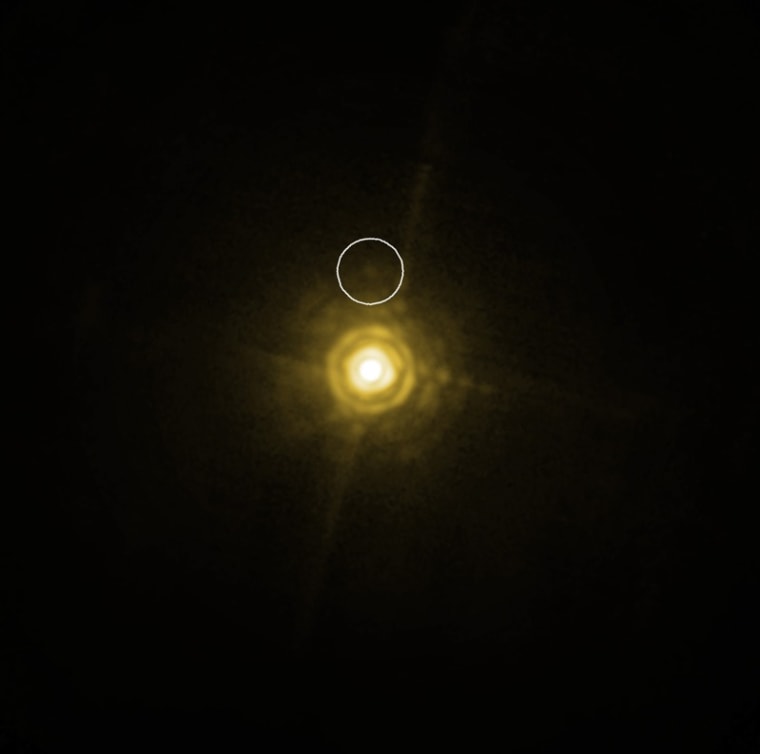

For the first time, astronomers have directly detected the light signature of a planet orbiting an almost sunlike star.

This signature can tell scientists the chemical makeup of the planet, which can help them understand how it formed. In the future these signatures could be used to look for signs of life on other planets.

The planet is a giant, about 10 times as massive as Jupiter, and it orbits between two other giants around a star similar to our sun in a scaled-up version of our own solar system.

The three giant companions were detected in 2008 and range in mass from seven to 10 times that of Jupiter, with orbits between 20 and 70 times as far from their host star as Earth is from the sun. The system also features two belts of smaller objects, similar to the asteroid and Kuiper belts around our sun. The system's star is about 1.5 times as massive as the sun.

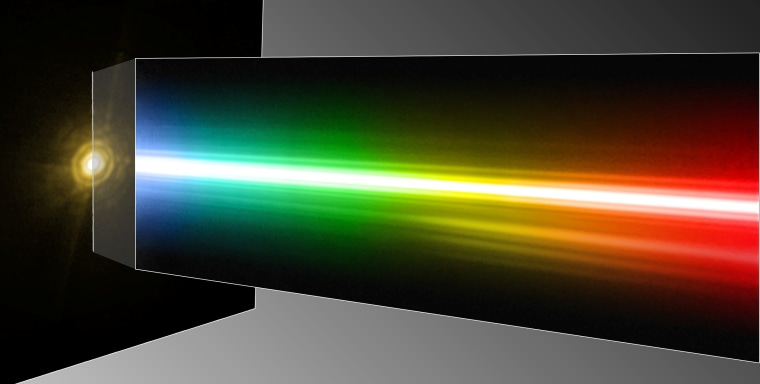

Previously, scientists have taken the spectra of stars — or the signature of the amount of light they reflect and radiate at different wavelengths — by watching an "exoplanetary eclipse" with a space telescope. As the exoplanet passes directly behind its host star from the perspective of Earth, the light that comes only from the planet can be subtracted out from that that comes from the star.

But this method can only be used on the small fraction of exoplanets that have the right kind of orientation with respect to the Earth.

The team of astronomers that observed the giant planet were able to do so without looking for an eclipse, instead detecting the planet's light directly with a ground-based telescope: the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile.

"After more than five hours of exposure time, we were able to tease out the planet's spectrum from the host star's much brighter light," said team member Carolina Bergfors.

Picking out the planet's light is tricky because the host star is several thousand times brighter than the planet.

"It's like trying to see what a candle is made of, by observing it from a distance of two kilometers [1.2 miles] when it's next to a blindingly bright 300 Watt lamp," said team member Markus Janson of the University of Toronto.

The light spectrum of the planet can show what the atmosphere of the world is like, though in this case it reveals that the atmosphere is still poorly understood, not matching up to any current models.

Eventually, though, scientists hope to be able to more easily detect chemical signs of life on other worlds by their signatures in light spectra. Certain molecules that are important to life or a potential sign of it that have been found are carbon dioxide, water vapor, silicate minerals and sodium.

The team hopes to use the same methods to get the spectra of the other two giant planets in the system, to do a comparison between them.

"This will surely shed new light on the processes that lead to the formation of planetary system like our own," Janson said.