Special legislative favors, especially one designed to secure a Nebraska senator's vote for the embattled health care package, ignited so much public outrage that President Barack Obama is calling them a mistake and House leaders say the bill can't be resurrected unless such sweetheart deals are scrapped.

Obama says Americans were understandably upset by the backroom dealmaking that he called ugly. In a cruel twist, the reaction helped elect a Republican senator in Massachusetts last week, putting the health legislation in peril.

Rep. Jim Clyburn of South Carolina, the No. 3 House Democrat, said Tuesday the House may be able to pass the Senate health bill — and salvage Obama's top domestic priority — if the offending items are deleted.

"We've got to get rid of that Nebraska stuff, we've got to get rid of the Louisiana stuff," Clyburn said, referring to provisions inserted to help secure the votes of holdout Democratic senators Ben Nelson of Nebraska and Mary Landrieu of Louisiana.

Obama, speaking to ABC News this week, said, "I didn't make a bunch of deals." But he acknowledged making "a legitimate mistake" by letting White House and congressional negotiators include the items during last month's closed-door negotiations.

Most ire has focused on the Nebraska provision, even though it resembled countless other favors that have secured lawmakers' votes for decades. Republicans caught Democrats flatfooted by turning derision of the "Cornhusker Kickback" into a national furor.

Strategists say Democratic leaders underestimated their foes' ability to use the Internet and other outlets to feed unsavory depictions of legislative dealmaking to angry voters already suspicious of Congress.

"The political dynamics have changed," said Democratic consultant Chris Kofinis. "The Google electorate," he said, can swap political information and opinions with lightning speed. Average Americans may know little about congressional traditions for brokering deals, he said, but when they hear about it, "they don't have a lot of patience for the sausage-making process."

Obama basically conceded the point this week, after reaction to the Nebraska item helped Republican Scott Brown win a stunning victory to succeed the late Sen. Edward Kennedy in Massachusetts. Brown's election jeopardized the health care overhaul that Kennedy long championed by taking away the 60-vote Democratic supermajority and the Democrats' ability to cut off GOP filibusters.

"It's an ugly process and it looks like there are a bunch of backroom deals," Obama told ABC News. In Wednesday night's State of the Union address, he said, he will "own up to the fact that the process didn't run the way I ideally would like it to and that we have to move forward in a way that recaptures that sense of opening things up more."

He said he has kept "the promises we made about increased transparency" at the White House, even though he once had advocated televising health care negotiations on C-SPAN.

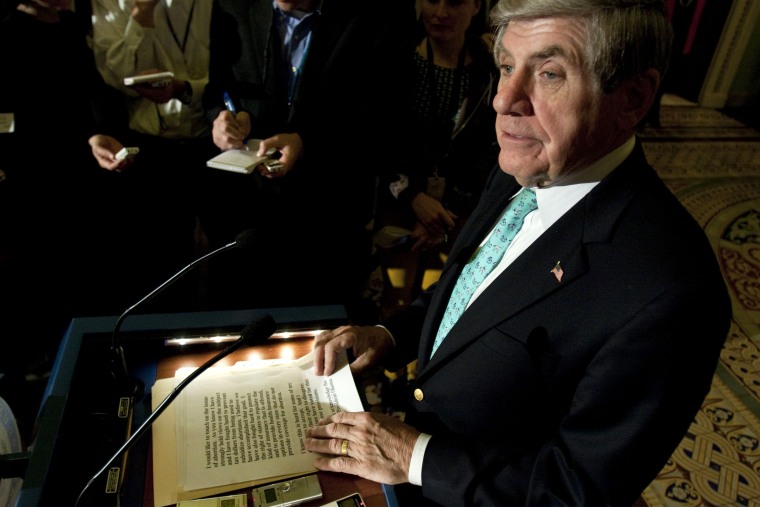

Nelson, who defended his actions in a Senate speech Monday, was upset last year that Nebraska would have to pay for a proposed expansion of Medicaid starting in 2017. He says he argued that the federal government should cover the full cost for all 50 states, not just Nebraska.

But such an agreement would have cost about $35 billion over 10 years. So White House and Senate Democratic negotiators agreed to apply the break only to Nebraska, at a cost of about $100 million, Senate officials said.

As soon as GOP operatives spotted the change, they dubbed it the "Cornhusker Kickback," and denounced it as a blatant payoff for Nelson's vote. Democratic leaders, knowing that both parties have often used such tactics to placate holdout lawmakers, seemed slow to react.

The most immediate impact was in Massachusetts, where Brown was running an under-the-radar campaign against heavily favored Democrat Martha Coakley. With conservative talk shows and bloggers fueling the fire, Democrats belatedly realized that Brown was surging.

"That Nebraska thing is really hurting us," former President Bill Clinton told House Democrats a few days before the Jan. 19 Massachusetts special election.

In a final-hour campaign speech, Brown denounced "those backroom deals for Nebraska and others."

A post-election poll by The Washington Post, the Kaiser Family Foundation and Harvard University found that Brown hit a nerve, even though Massachusetts voters had mixed feelings about health care in general. Nearly half said they opposed Obama's health initiatives. But 68 percent said they favored their own state's universal health care plan, which Massachusetts enacted several years ago — with Brown's vote.

Worcester teacher Kathleen Halloran, 47, told The Associated Press that a national health care revision "really needs to be a collaborative effort at real, true reform, not some political agenda, not these backroom deals where Nebraska gets exempt."

Nelson says he feels unfairly targeted by taunts of a "Cornhusker Kickback," when all he wanted was to stop Congress from imposing more unfunded mandates on the states. He said he was slow to realize the firestorm's impact because he was more focused on other matters, such as blocking a publicly run health insurance program.

Asked about the condemnation of the Nebraska deal, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., said Tuesday, "All senators, Democrats and Republicans, work hard to represent the states and the needs of their states."