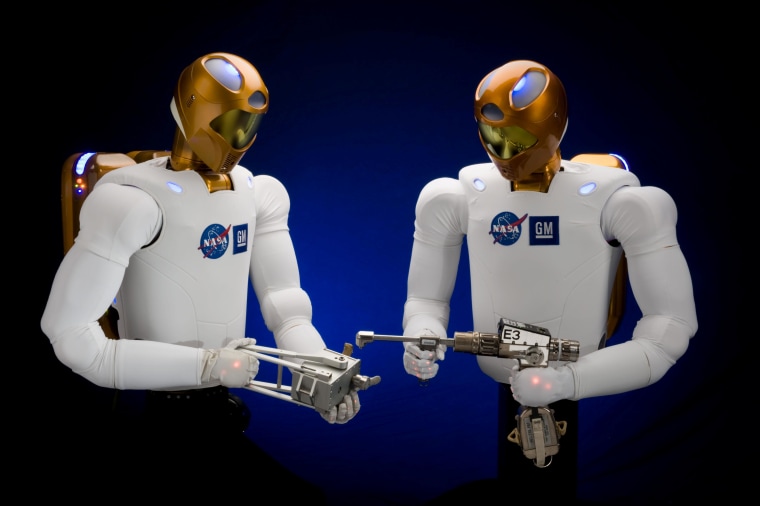

Engineers from NASA and General Motors have jointly developed what they tout as “the world’s most dexterous robot” called “Robonaut2” to supplement human activity both in space and in the factory.

The robot, called "R2" for short was built to replicate the appearance of a human from the waist up so that it can fit into and work in the same spaces, doing the same jobs as people do, sometimes right alongside them.

Robonaut2 is the newer sibling of Robonaut, a robot previously created by NASA and the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to do the same types of tasks that human spacewalkers do. Robotnaut2 replicates a human torso, head, arms, hands and fingers. GM and NASA are examining various “mobility solutions,” such as legs, for the robot, but future iterations may instead have wheels or maybe a single leg.

“We are always looking at different mobility options,” said Ron Diftler, Robonaut project manager for NASA. “We are looking at a variety of lower bodies and not necessarily a conventional lower body.” Robots working on the International Space Station, for example, may need to attach themselves using footholds designed for humans’ feet, so they could have a single leg to fix them in that location, he said.

To get there, they could crawl along from one hand-hold to another, just as the astronauts do, Diftler said. Factory robots, in contrast, may have no need for mobility at all.

To accomplish nearly human dexterity in the hands and fingers, in a package the same size and shape as human hands and fingers, the engineers mimicked biological solutions to the problem.

“I learned a lot more about the anatomy of the hand than I ever thought I would,” said Alan Taub, General Motors’ vice president of research and development.

That was because it proved to be a daunting design to match. The engineers concede they can’t yet top nature’s work.

“In degrees of freedom it still falls short of a human being, particularly in the thumb,” Taub said. “It is as close to human hand as we could (get) with the packaging limitations." The designers achieved this by employing “the equivalent of tendons” to operate the fingers, rather than using direct-controlled motors in the hands, Taub said.

GM history with NASA

GM has a history with the space program, supplying the lunar rover used during the later Apollo missions in the early 1970s. Today, the company stands to benefit from earthly applications of its work with the space agency as much as the astronauts do. Taub and Diftler declined to say how much it cost to develop the two Robonaut2 robots, but characterized the project as “very expensive.”

The current political discussions regarding NASA's future plans make it difficult to estimate when the agency might create a version of Robonaut2. But GM says after it determines exactly what tasks its version will perform, it will seek a partner to build it from the community of industrial robot manufacturers.

The problem with the robots GM uses today is that they are proverbial bulls in a china shop, thrashing about as they work without regard to anything or anyone nearby.

“When we install a robot (in a factory) we spend more money on cages and protection systems than we do on the robot,” said Taub.

Robonaut2 is gentle compared to these industrial robots in part just because it is smaller, he said. “It is a much more compact robot because it is basically in the shape of a human.” Big steel machines have a lot of inertia in their movement that makes them inherently hazardous for anyone nearby. “Those other robots have long arms, so even if you wanted to stop it there is a lot of mass.”

In contrast, Robonaut2’s arms are small and light, with excellent sensors to ensure they stop if they come in contact with something unexpected. “It has a very elegant sensing system so it can sense resistance in the arm,” said Taub. “A child’s hand will stop it.”

This dexterity will let a descendant of Robonaut2 handle flexible materials like space blankets aboard the space station, Diftler said. Space blankets aren’t how robots stay warm at night. They use the same flexible shielding NASA does to protect the station from micrometeorites and from a solar blast in orbit.

On Earth: Welding for starters

GM typically uses its robots for welding and a variety of repetitious or awkward assembly chores, he said.

When GM searched for a suitable partner to research robotic technology, it concluded that NASA’s work on Robonaut, which began a decade ago, was the most directly applicable to its needs and sent a team of engineers to the Johnson Space Center in Houston to collaborate with NASA’s team to develop Robonaut2.

“We went around the world and were pleasantly surprised to find that the robot we were looking for had been developed at NASA,” said Taub.

The car guys weren’t just there to learn from the rocket scientists; they were key contributors to the robot’s development. “We have a better Robonaut as a result of working with GM,” said Diftler.

Next, engineers working on the project will develop the know-how from Robonaut2 into devices NASA and GM can each use. A key issue is whether the robots will be remotely operated devices controlled by humans or whether they will operate autonomously following scripted actions.

GM’s plan is for its version of the robot is to work autonomously, doing precision assembly work without human intervention. NASA initially thought it was looking for a remotely operated device, but quickly came to appreciate the benefits of robotic autonomy.

“The robot could simply mimic the action of the astronaut (inside the space station), but we’re trying to use that mode less now,” Diftler said. The next step is for the robot to work outside the station alongside an astronaut, using its cameras and sensors to detect the astronaut attempting to do a task, perform that task.

But better still will be when the robot can simply be told what to do and with careful observation from people on the ground, do the work without the astronauts having to do anything, Diftler said.

This kind of capability also has utility for GM, as car makers plan for the day when cars will be able to drive themselves.

“An autonomous vehicle is a robotically driven vehicle,” said Taub. “The synergy with all the technologies we are putting on our vehicles is tremendous. The vision systems are the same. The control architecture is the same.”