People in the eastern United States will get a great opportunity, weather permitting, to see the space shuttle Endeavour launched into orbit. And it will also likely be the very last opportunity ever to see a space shuttle blast off at night.

This flight (STS-130) will be the 32nd to rendezvous and dock with the International Space Station. It is the first of NASA's five final shuttle missions this year before the fleet is retired in the fall.

Out of the 129 previous shuttle launches, 29 have occurred in complete darkness. The very first night launch of a space shuttle (Challenger) was STS-8, which took place on Aug. 30, 1983. There have also been seven Shuttle launches that occurred during twilight, four at dawn and three at dusk.

This upcoming mission was originally scheduled to launch on Feb. 4 during morning twilight, but it was later rescheduled for the predawn hours.

To reach the space station, Endeavour must be launched when Earth's rotation carries the launch pad into the plane of the station's orbit. If Endeavour had lifted off on Sunday, that would have happened at 4:39 a.m. ET. The launch was delayed on Sunday due to weather concerns, however.

Each day of delay pushes the launch time 22 to 26 minutes earlier. Future launch opportunities include 4:14 a.m. ET on Monday and 3:51 a.m. on Tuesday. Should weather or technical issues delay the launch until Feb. 22, liftoff would then be scheduled for 9:48 p.m. ET.

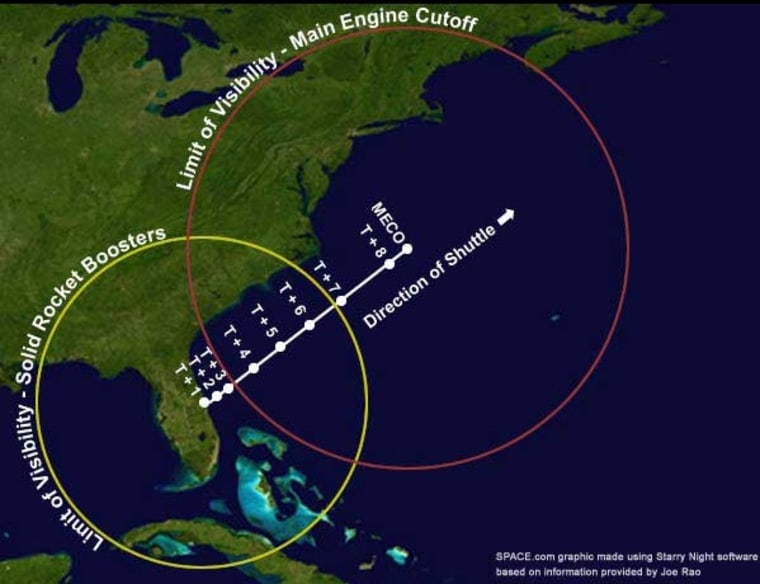

As has been the case with other launches to the space station, Endeavour's liftoff will bring the shuttle's path nearly parallel to the U.S. East Coast, and the glow of the shuttle's engines will be visible along much of the Eastern Seaboard. A Space.com map shows the area of visibility.

After this mission, there will be just four more flights left before the shuttle program finally comes to a close (tentatively set for September 2010). Two of these are scheduled to be launched during early afternoon, and one during the midday hours.

Interestingly, however, STS-134, which will also be Endeavour's final planned flight, is currently scheduled for a July 29 launch, just a little over an hour after sunrise.

If weather or technical constraints were to delay that mid-summer launch by about a week, then it too would be launched prior to sunrise and the first light of dawn, also making it a night launch. Odds are probably long for that scenario to happen, however, so this month's liftoff will likely be the last nighttime launch of a space shuttle.

What to expect

The brilliant light emitted by the two solid rocket boosters will be visible for the first 2 minutes and 4 seconds of the launch, out to a radius of 520 statute miles from the Kennedy Space Center — an area more than three times the size of Texas.

Depending on where you are located relative to Cape Canaveral, Endeavour will become visible anywhere from a few seconds to just over 2 minutes after it leaves Pad 39-A. For an example of what all this looks like from Florida, see video of a night launch made by Rob Haas from Titusville, Fla., on Dec. 9, 2006 (the STS-116 mission).

After the solid rocket boosters are jettisoned, Endeavour will be visible for most locations by virtue of the light emanating from its three main engines. It should appear as a very bright, pulsating, fast-moving star, shining with a yellowish-orange glow.

Based on previous night missions, the brightness should be at least equal to magnitude -2; rivaling Sirius, the brightest star in brilliance. Observers who train binoculars on the shuttle should be able to see its tiny V-shaped contrail.

Observer James E. Byrd shot video of the shuttle from Virginia after a November 2000 night launch. The bright star Sirius briefly streaks through the scene giving a sense of scale and brightness to the shuttle's glow.

Where to look

- Southeast U.S. coastline: Anywhere north of Cape Canaveral, viewers should initially concentrate on the south-southwest horizon. If you are south of the Cape, look low toward the north-northeast. If you're west of the Cape, look low toward the east-northeast.

- Mid-Atlantic region: Look toward the south about 3 to 6 minutes after launch.

- Northeast: Concentrate your gaze low toward the south-southeast about 6 to 8 minutes after launch.

For most viewers, the shuttle will appear to literally skim the horizon, so be sure there are no buildings or trees to obstruct your view.

Depending upon your distance from the coastline, the shuttle will be relatively low on the horizon (5 to 15 degrees; your fist on an outstretched arm covers about 10 degrees of sky). If you're positioned near the edge of a viewing circle, the shuttle will barely come above the horizon and could be obscured by low clouds or haze.

If the weather is clear, the shuttle should be easy to see. It will appear to move very fast; much faster than an orbiting satellite due to its near orbital velocity at low altitudes (30-60 mi). It basically travels across 90 degrees of azimuth in less than a minute.

Shuttle in motion

Endeavour will seem to "flicker," then abruptly wink-out about 8 minutes and 24 seconds after launch as the main engines shutdown and the huge, orange, external tank (ET) is jettisoned over the Atlantic at a point about 800 statute miles northeast of Cape Canaveral and some 430 statute miles southeast of New York City.

At that moment, Endeavour will have risen to an altitude of about 340,000 feet (64.4 statute miles), while moving at roughly 17,500 mph (Mach 24.6) and should be visible for a radius of about 770 statute miles from the point of Main Engine Cut Off (MECO).

Following MECO and ET separation, faint bursts of light caused by reaction control system (RCS) burns might be glimpsed along the now-invisible shuttle trajectory; they are fired to build up the separation distance of the orbiter from the ET and to correct Endeavour's flight attitude and direction.

And of course, before hoping to see the shuttle streak across your local sky, make sure it has left the launch pad!

Assuming a good load for Endeavour's fuel cell system, the shuttle should be able to make a number of launch attempts over a 15-day time span, extending to Feb. 22. However, NASA is trying to launch Endeavour ahead of an unmanned Atlas 5 rocket carrying the agency's new Solar Dynamics Observatory, a sun-watching probe now slated to blast off no earlier than Wednesday from the nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

Getting views during the mission

During Endeavour's 13-day mission, both the shuttle and the International Space Station will be visible during the predawn hours across North America and Europe.

Observers across the northern U.S. and Canada will have visibility through all 13 days, but those living farther south will have views only during the first few days and possibly the final day or two of the mission. Unfortunately, across the southern United States, no visible passes are predicted to occur.

During the mornings of Feb. 8, 9, 19 and 20 it may be possible to see Endeavour and the space as two separate entities, appearing as bright moving "stars." At all other times during the mission, you'll see only one singular bright moving star, as that will be when the two space vehicles are docked together.

So what is the viewing schedule for your particular hometown?

You can easily find out by visiting one of these four popular Web sites: Chris Peat's Heavens Above, Science@NASA's J-Pass, NASA's SkyWatch and Spaceweather.com. Each will ask for your zip code or city, and respond with a list of suggested spotting times. Predictions computed a few days ahead of time are usually accurate within a few minutes. However, they can change due to the slow decay of the space station's orbit and periodic reboosts to higher altitudes. Check frequently for updates.

Another great site is this one, which provides real-time satellite tracking and shows you at any given moment during the day or night over what part of the Earth the space station or shuttle happens to be.

This report was updated by msnbc.com.