The tsunami alerts issued in the wake of Saturday's earthquake in Chile demonstrate how much more information is available about potential seismic threats, more than five years after the catastrophic Indian Ocean quake and tsunami.

In 2004, emergency officials in a region stretching from Indonesia to India were slow to pick up on signs that the Sumatra quake generated a deadly series of ocean waves. This time around, officials issued the first tsunami warning at 1:46 a.m. ET Saturday, just 12 minutes after the magnitude-8.8 quake hit Chile.

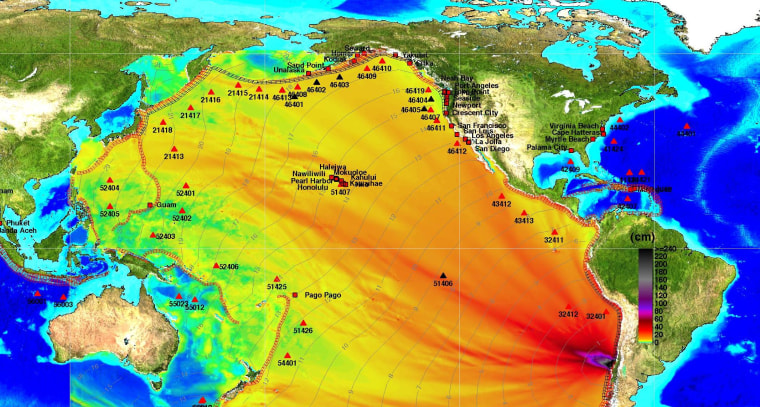

Because of the way the seismic wave was projected to propagate, the warning focused on Hawaii. The first waves were projected to arrive at 11:05 a.m. Hawaii time (4:05 p.m. ET), more than 14 hours after seismic activity began in Chile. Residents were told to take "urgent action" to protect lives and property.

The waves came somewhat later than projected, and appeared to be smaller than many people feared. The largest reported waves rose to a height of 6 feet (2 meters) or so.

A tsunami watch, which is a lower level of alert, was issued for the U.S. West Coast as well. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said regions around the Pacific Ocean's "ring of fire" should be on the alert for higher waves as much as 24 hours after the initial shock.

NOAA divides responsibility for Pacific tsunami monitoring between two centers: One is located at Ewa Beach on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, and issues alerts for Hawaii and the Western Pacific. The other is in Palmer, Alaska, and focuses on Alaska and the West Coast.

Tsunami-watchers monitor a network of seismic sensors that has expanded dramatically since 2004. Back then, there were only four instruments in the Indian Ocean transmitting seismic data in near real time. That number has risen to more than 50. Back then, about 20 seismometers were watching for earthquake activity around the Pacific Rim. Today there are more than 200. The number of tide gauges has more than doubled over the past five years, to 400.

Satellite communication systems pass along readings from many of those sensors every 15 minutes or less.

Tsunami-watchers admit that the warning system is still far from perfect. Forecasters rely on computer models to take the data from widely spread sensors and figure out which way the waves are heading. And the models are constantly being tweaked to reflect real-life events.

There's also an issue relating to maintenance of the sensor network: Last year, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility issued a report pointing to what it said were "gaping holes" in the tsunami warning system. NOAA's records indicate that 10 out of its 39 deep-ocean pressure monitoring stations, also known as DART buoys, were failing. Still more deep-ocean sensors operated by other countries are on the blink.

Officials at NOAA acknowledge that keeping the stations in operation can be a problem, and they've asked mariners to help out by staying well away from the buoys and reporting any damaged or drifting buoys to the U.S. Coast Guard.

This report is an updated version of a Cosmic Log posting that was first published in September 2009. A version of this report mischaracterized the number of instruments reporting seismic data in close to real time.