Google’s face-off with Beijing over censorship may have struck a philosophical blow for free speech and encouraged some Chinese Netizens by its sheer chutzpah, but it doesn’t do a thing for Internet users in China. It merely hands the job of blocking objectionable content back to Beijing.

Its more lasting impact may lie in the global exposure it has given to the Chinese government’s complex system of censorship – an ever-shifting hodgepodge of restrictions on what information users can access, which Web tools they can use and what ideas they can post.

“You can only guess what the rules are,” said Zhao Jing, a Chinese free-speech activist whose popular blog was deleted by censors from its host server in 2005. “It means you should self-censor, limit your mind and be cautious, because you have no idea where the line is.”

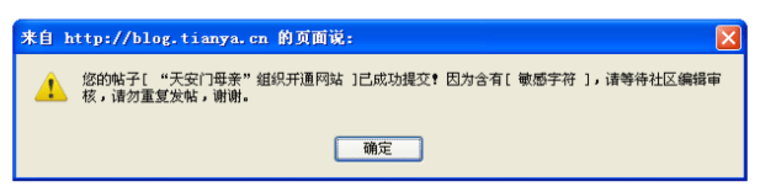

Censorship in China is unpredictable in part because it employs an array of tools — combining cutting-edge filtering algorithms and software that detects taboo keywords with the blunt instruments of the government’s old propaganda machine. It takes place at different levels, involving government agencies and the private sector.

“The point of confusion is who is doing what,” says Nart Villeneuve, a cyber security professional and research fellow at the University of Toronto who has done detailed analysis of Chinese Internet censorship. Frequently, what observers assume is blocked by Beijing, is actually taken out of the public arena by Internet companies trying to read the government’s will, he said.

One tool in the toolbox

The so-called “Great Firewall,” as China's censorship system is known, filters out politically sensitive material, as well as gambling sites and pornography originating outside China. It reportedly blocks thousands of sites, including those of human rights groups, organizations that promote Tibet or Taiwan independence and Chinese dissident groups.

The firewall also censors by keywords, causing infuriating interruptions in service.

For example, if an Internet surfer in China searches for the term “Falun Gong” —a banned and harshly suppressed religious group — the firewall responds by sending a reset packet to his or her computer that results in the display of a default error page. It also causes a gap in service preventing subsequent searches -- even on innocuous topics.

“If you try to look for a URL path with a banned word or phrase, it will halt your connection, even if the site is not blocked,” said Villaneuve, who runs tests to determine at what point censorship occurs in China.“Then you can’t do a normal query for a little while.”

Making surfing even more complicated, the taboos are always changing, depending on the political winds.

After bloody ethnic clashes erupted last summer in China’s predominantly Muslim territory of Xinjiang, the news spread quickly the Internet. Beijing blamed the rioting on ethnic Uyghur separatists organizing through the Web, and shut down Internet access throughout the region, along with text messaging and international calling in some areas.

At that point, Beijing also blocked Twitter for all of China, and other popular social networking and sharing sites, including Facebook, YouTube and Flickr. Those roadblocks remain in place eight months later.

For the vast majority of people in Xinjiang, access to the Internet is still severely restricted. The general public can view only a few sites hand-picked by authorities, including the state-run Xinhua News Agency and People’s Daily — and two Chinese portals, according to the China Daily. Elsewhere in China, despite censorship, Internet users have access to tens of thousands of foreign and domestic sites.

Occasionally, China also unexpectedly unblocks Web sites. When the capital was flooded with athletes and tourists for the Beijing Olympics in August, for instance, the BBC and Voice of America, which usually are blocked, were suddenly available.

Within the wall, “self-discipline”Arguably, the most stringent censorship in China is conducted by the private sector. The government puts the responsibility for monitoring and censoring material originating inside China on companies that provide Internet service — search engines, portals, social networking sites, chat rooms or photo and video-sharing sites.

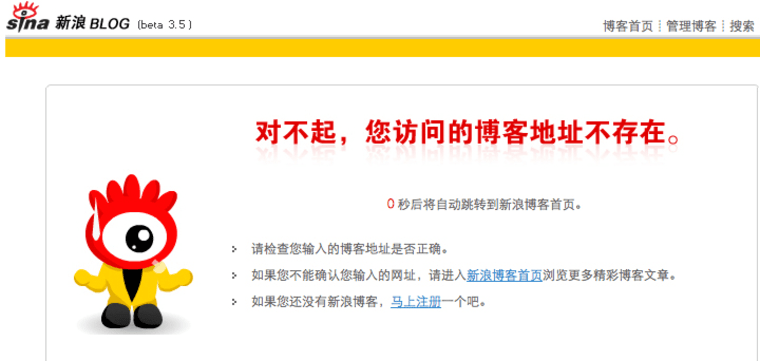

Every search engine or blogging site in China reportedly has a department dedicated to filtering, reviewing and deleting material that the censors know — or guess — the government does not want the public to see. If they get it wrong, these companies risk losing their operating licenses.

A number of video-sharing sites have suffered this fate, as well as the Chinese blog site, Bullog.cn, known for edgy political commentary and counter-culture fare. When the government shut the site in January 2009, amid an anti-porn it crackdown, it accused the site of hosting “low and vulgar” content.

Two popular micro-blogging services similar to Twitter were suspended last July, about the same time that the foreign social networking sites were blocked, for refusing to edit or delete content. The larger of the two, Fanfou, boasted more than a million users before it ran afoul of authorities.

“Either the Web site censors sensitive feeds or the Web site will be censored,” Fanfou founder Wang Xing wrote in one of his last posts on the site, according to a report in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post. “This uncomfortable, but necessary decision has to be made.”

Self-discipline is portrayed as a patriotic duty by the government, which confers annual “Internet Self-Discipline Awards” to industry executives for effectively censoring themselves.

But the way “self-discipline” is carried out varies widely among the companies because the government provides only broad guidance, not detailed instructions. While there are topics that are universally understood to be taboo — anything supportive of Falun Gong, for instance — interpretation of the rules varies widely.

For that reason, it is easy to mistake unexpected content for an intentional policy shift, when it may indicate only that censorship is very patchy in China. On March 16, for example, we reported on this site that Google appeared to have stopped censoring its Chinese site, because searches on the site produced surprisingly sensitive content, including the famous “Tank Man” image from the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. That conclusion was incorrect, censorship researcher Villeneuve concluded after running some tests, which showed the same content showing up on other search engines in China.

Google’s China initiativeIn general, however, Google’s experience in China is a good example of how differently censorship is handled from one company to the next.

“When Google first arrived in China in 2006, it consistently blocked less material than Baidu (a Chinese search engine that dominates the domestic market),” said Rebecca MacKinnon, visiting fellow at Princeton University’s Center for Information Technology and a former China journalist.

Its search engine, Google.cn, also tried to remain transparent to users. When material was removed from its search results, the company posted a message at the bottom of its results pages: “Pursuant to local laws, regulations and policies, a portion of the search results are not displayed,” in effect alerting users to the censorship.

“This is how Google executives justified the ethics of their presence in China,” said MacKinnon. “Chinese users, they argued, were still better off with Google.cn than without it.”

But over the last 12 to 14 months, MacKinnon and other experts say, as Beijing started blocking more sites, pressure also grew on Internet providers, including Google, to censor more stringently.

Google responded by announcing it would stop censoring information and would instead reroute users in China to Google.hk, its Hong Kong search engine. But that does not mean that its customers in mainland China will gain full access to the Internet, as users in Hong Kong have.

Although Hong Kong reverted to Chinese rule in 1997 after 100 years of British control, it still operates under a different set of rules from the mainland, with nearly complete press freedom, unfettered access to the Internet and multi-party elections. But Internet companies in Hong Kong are treated like foreign companies, and are subject to filtering and blocking by the Great Firewall as material enters China’s domestic Web network.

Business as usual

To be sure, most of China’s 384 million Internet users log on for mundane reasons that don’t challenge the limits of free speech. A lot of Chinese citizens also accept the notion that stability and continued economic growth depend on government controls, including censorship.

And Beijing has been largely successful at keeping a lid on sensitive information while using the Internet to fuel economic development.

“Lack of free information will catch up with China in the end, hobbling the spirit of free inquiry at the heart of science and of innovation,” said Kaiser Kuo, an American writer and independent tech consultant in Beijing. “The indirect effects, and the long-term impact, are profound, but I think it's only fair to point out that the direct effect is relatively small.”

Blog madnessEven with censorship, the free-wheeling Internet— especially user-generated content — is a dramatic departure from tradition inside China, where the state controlled news and information with an iron grip for decades. Under that system, the central government disseminated the party line to state-owned newspapers, radio and television, which reported accordingly. Circulation of foreign papers in China was restricted.

As the Internet became available to the public in the early 2000s, at first through cybercafé’s that proliferated in cities, and then through widely available in-home and office connections, the government’s ability to control the flow of information began to unravel. When Web 2.0 arrived, allowing ordinary citizens to publish independently, Chinese people jumped at the opportunity.

The first blogs in the country appeared in 2004,and there were 47 million Chinese bloggers just three years later, according to official statistics.

The way blogs are handled suggests that the blog-hosting sites have broad discretion over censorship, apparently by using various combinations of keyword flagging and human monitoring, according to MacKinnon, the Princeton fellow and former journalist.

On some blogs, politically sensitive posts are blocked at the publication stage, she said, while others are delayed for “moderation” and then posted -- or not. Some are posted only in private view, so only the author can view them.

In 2005, in one display of “self-discipline,” the staff of Microsoft Live Spaces in China deleted the entire blog written by Zhao Jing, under the pseudonym Michael Anti, sparking an international outcry over the move.

More commonly, single blog entries disappear 24 hours or so after they are posted. That has created a tendency among knowledgeable Chinese Web surfers to quickly squirrel away potentially sensitive information that they encounter.

“People who have been around Internet in China will quickly save an item offline, because the link might disappear,” said MacKinnon. “The same goes for photos and so on.”

In some cases, Beijing turns from the high-tech to the blunt old-fashioned instruments of censorship — arrest and intimidation, as it did in the case of writer Liu Xiaobo.

In 2008, Liu co-authored a manifesto calling for democracy in China, which was signed by 303 prominent Chinese intellectuals. Police arrested Liu at his Beijing home just as the document was released on the Internet. Censors quickly went to work expunging material about Liu and the document from the Internet, but not before the manifesto circulated widely and garnered some 10,000 signatures of support.

In December, after Liu had spent a year in prison, a Chinese court convicted him of subversion and sentenced him to 11 years in prison.

The digerati fight backFree speech advocates, human rights activists and liberal intellectuals in China have developed a bevy of ways of getting around Internet controls.

In posting comments and blogs, they alter spellings, substitute acronyms for sensitive words, or substitute Chinese characters that sound the same but are written differently than the sensitive term they are trying to use. As the censors catch on, they move on to new strategies.

Using VPNs (virtual private networks) and proxy servers, tech-savvy Chinese users also can access materials that are otherwise blocked by the Great Firewall.

Despite being barred in China, Twitter is growing fast among people who can circumvent the firewall. According to Zhao Jing, the journalist and former blogger, he had 3,000 followers on Twitter before Twitter was officially blocked in July. Now, he said, he has 17,000. Throughout China, he said, there are 50,000 Twitter users, including many activists, liberal lawyers, professors and journalists.

Meanwhile, he said, even the domestic micro-blog services, though subject to controls, are delivering unvarnished news so quickly that it is difficult to censor. What’s more, news from remote parts of the country that once could have been easily suppressed now finds its way into the state-run press, he said.

“In 2009, we saw that many local events, protests, complaints were conveyed by cell phones and text messages and email from ordinary people, from non-profit organizations … to friends, and then Tweeted and reTweeted,” and sometimes picked up by reporters in the state press, said Zhou. “A local protest can easily become a national issue.”

Web 2.0, even in the hands of a relatively few Chinese, will eventually pave the way for a birth of a free press and democratization in China, Zhou believes.

“The Internet was the Gods’ first gift to China,” he said. “Twitter is the second.”