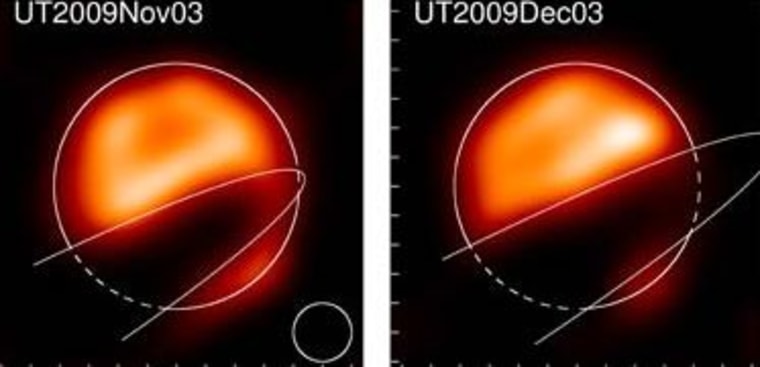

New images of two strange stars, where one passes in front of the other to block its light periodically as seen from Earth, are beginning to give up the secrets of this puzzling stellar pair.

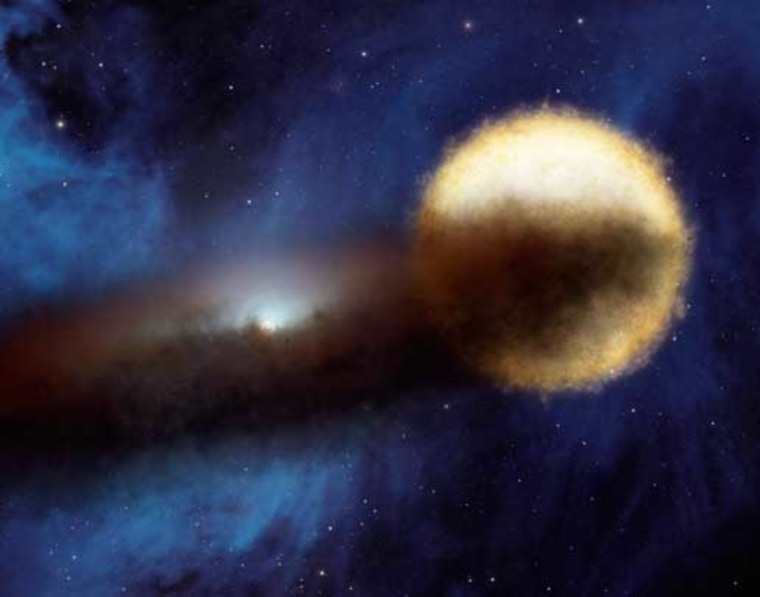

The star system, called Epsilon Aurigae, experiences the eclipse once every 27 years. For the first time, scientists have directly imaged the dark companion that blocks its companion's light.

Astronomers have been watching this pair of stars since the 1800s. Over time, they noticed that the main star appears dimmer than it should be, given its mass, and that its brightness dips even more for longer than a year every few decades. The system lies about 2,000 light-years from Earth (a light-year is the distance light can travel in one year).

Scientists had previously surmised that the bright star has a hidden companion that was blocking its light, and the new observations confirm that.

"Seeing is believing," said study leader John Monnier, an astronomer at the University of Michigan.

Astronomers have also wondered why this star companion was so difficult to see.

Some researchers have suggested that it is a faint star with a thick cloud of dust orbiting it, obscuring some of its light. But the alignment of the cloud, the star, its companion and Earth would have to be just right for this to be the case.

And indeed, the new data support this idea.

"This really shows that the basic paradigm was right, despite the slim probability," Monnier said. "It kind of blows my mind that we could capture this. There's no other system like this known. On top of that, it seems to be in a rare phase of stellar life. And it happens to be so close to us. It's extremely fortuitous."

The astronomers used the Michigan Infra-Red Combiner instrument, or MIRC, to combine the light entering four telescopes at the CHARA array at Georgia State University. The effect is a virtual telescope that is much larger than its four constituents.

The researchers detail their findings in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature.