Three years after the massacre of 32 students and faculty at Virginia Tech, campuses around the country have beefed up their emergency notification systems, some with more sophisticated and varied programs than others.

Colleges and universities that use text-messaging systems for emergency notification have differing degrees of enrollment by students. "We are almost at 100 percent, and I guess you'd expect us to be that way," said Larry Hincker, Virginia Tech's associate vice president of university relations. "Other universities I've talked to, they're happy if they get 30 or 50 percent enrollment from students" for emergency text messages to be sent to their phones.

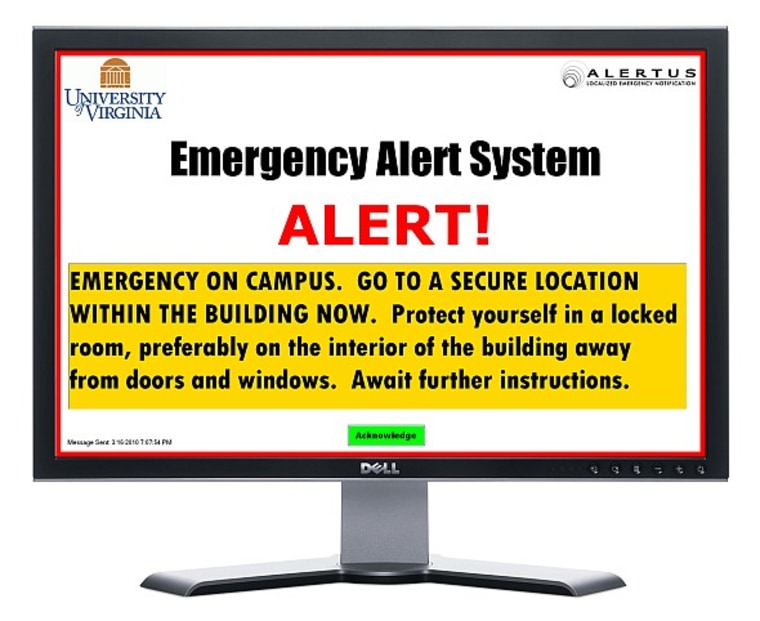

Sending text messages — initially thought by some to be the best means to get the word out in an emergency situation — is not the only tech approach being used. Facebook, Twitter and computer desktop alerts, campus television interruptions are also being embraced by schools. Lower-tech means, like public address systems, as well as digital displays spread around the campus and in classrooms, are also becoming more common.

Campus Safety magazine polled "campus protection officials" last spring and found that 87 percent said their schools currently use text messaging for emergency alerts, and that an average of 48.9 percent of students sign up for such programs.

Broader focus now

"Three years ago, the sole focus was on text messaging for emergency notification," said Ara Bagdasarian, CEO of Omnilert, makers of the e2Campus unified emergency notification system, used by more than 750 colleges and universities.

"Subsequently, there has been more of an expansion to sending out messages to multiple different kinds of communication end points, even though text messaging is still the most reliable, best way to get out mass messages in a very expedient fashion. And students have their cell phones with them all the time."

Students often don't sign up for text-message alerts because of privacy issues, but more likely because of "apathy," said Bryan Crum of Omnilert. "It’s not a fear of opting in, of giving up personal information," he said. "It's just a lack of interest."

And, "a faculty member who’s teaching cannot check their cell phone because they’re teaching class, so they need to be able to hear (news) over the public address system, or see the information on a digital sign in their classroom," Crum said. "Visitors walking across campus need to hear an alert or read it on a sign."

Don't rely on a single technology

Those are among the reasons for having "multiple communication methods by which people can receive alerts," Crum said. "Before it was just about text messaging, but now there are digital signs, PA systems, and even computer desktop pop-up alerts that will interrupt you while you're writing your paper."

"The one thing I tell my colleagues at other schools is, you better not rely on a single technology," said Hincker. "There is a cottage industry of mobile notification services that sprang up from Virginia Tech's tragedy. But you better not rely on one single technology. The reason is, as we saw even in our case, those systems can get loaded very quickly.

"If you have an emergency, you're going to get one, maybe two shots, to use those systems," he said. "And then after that, they’re going to degrade because everyone is going to start using those phones to call other people," tying up the network.

Criticisms about notification

An investigative panel criticized the university's communications failures and other problems that allowed nearly two hours to elapse between the first gunshots in a classroom after 7 a.m., April 16, 2007 and campus-wide notification using e-mail. Virginia Tech student Seung-Hui Cho killed 32 students and faculty before taking his own life that morning in the deadliest shooting rampage in U.S. history.

The panel concluded that lives could have been saved if alerts had been sent out earlier and classes canceled after the first burst of gunfire. In January 2009, when a graduate student used a kitchen knife to decapitate another student at a cafe on Virginia Tech's campus, the university's text message and e-mail alert system was put to a test. More than 60,000 messages were sent about 40 minutes after the slaying, which happened around 7 p.m.

"Some students said they didn’t get a message until 40 minutes later," after the first messages were sent, Hincker said. "But it was about 40 minutes after the event before I sent a notice ... Some people expect a university to send a campus notice out as soon as they get a 911 call; that’s just simply unreasonable."

In the 2009 case, "the murderer was in custody, but we still sent out a notice to the university community to apprise them of the event, but there was no threat to the university campus," he said.

Northern Illinois University shootings

A recent report by Northern Illinois University about the February 2008 shootings that took the lives of five students and injured 21 people praised the school's handling by authorities and communications to students and staff.

The university, as many others, consulted Virginia Tech officials after the 2007 tragedy. About 14 minutes after the shooting started at Northern Illinois University, warnings were sent by campus e-mail and posted on the school's Web site.

"I think they've done an excellent job. They had prepared and learned the lessons from Virginia Tech. It could have been far worse," Mary Kay Mace, the mother of one of the victims, told the Elgin Courier-News recently.

Since the shooting, the university has installed a new text message notification system, and also reworked its policies for who can get the word out — which needs to be as broad a base of people as possible, said Hincker of Virginia Tech.

Involving more staff

"There’s another lesson for us all," he said. "You need to have a lot of people that can do this ... We now have more than 30 people at the university who are trained on our emergency notification system. The bulk of them now are in the (campus) police department. They’re the ones who are staffed 24 hours a day, so if there is a notification that absolutely has to go out immediately, that’s the place where you know you have 24/7 coverage."

The International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators, in a report, also encourages schools to determine "who has the authority to activate the notification system."

A "universal messaging system," such as e2Campus, Crum says "eliminates all the human bottlenecks, the office politics, the bureaucracy that might occur otherwise — 'Oh, Bob's on vacation, and the temp doesn’t know how to update the Web site,’ or 'Fred’s at lunch, so nobody can start the PA system.' "

Hincker says Virginia Tech is paying about $35,000 a year for its notification service with Everbridge, a California company. The university will also spend nearly $750,000 for 500 digital signs that will be posted in classrooms and around campus.

Cost for text-messaging and other emergency notification systems is definitely a factor for many schools, and one of the top "barriers" cited by those in the Campus Safety magazine survey. Another is text message system enrollment by students.

"The most important thing to me is redundancy, having several means of getting the word out," said Hincker. "Any university that goes out and buys a text messaging system and thinks they're prepared for emergency notification is deluding themselves."