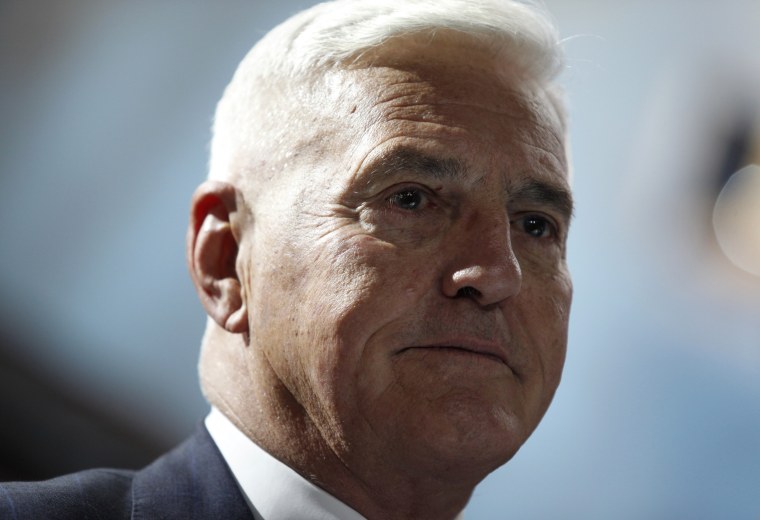

Boarding school couldn’t do it. Nor could his time in the Marines, where he learned to fly fighter jets. And if, after 50 years in the auto industry, Bob Lutz still hasn’t learned to keep his mouth shut, well, he’s retiring soon.

Of course, even then, anyone who knows the 79-year-old son of a Swiss banker expects Lutz will keep shooting from the lip as long as he’s got something to aim at.

Just back from a vacation in the Caribbean, his last as a GM employee, Lutz will spend the last two weeks of his tenure as Vice Chairman of General Motors cleaning out his various offices — one at GM headquarters in downtown Detroit, the other at the maker’s technical center, in suburban Warren, Mich. He retires on May 1.

But he will use a fair share of the time in conversation with young executives desperate to tap his wealth of knowledge — and chatting with reporters hoping to glean one more pithy headline.

With rare exception, Lutz has always been willing to oblige, like the time 20 years ago he glumly suggested his former employer, Chrysler, wouldn’t find a merger partner because, “You can’t find a bridegroom when the bride is on her death bed.”

Lutz has been equally outspoken since joining GM nearly a decade ago and already entering his 70s, well past the company’s normal mandatory retirement age. He has, for example, derided some of its older products as “angry appliances,” and even at this late date he takes shots at a 100-year-old company that celebrated its centennial by getting a federal bailout of about $50 billion.

GM repaid on Tuesday the $8.1 billion in loans it got from the U.S. and Canadian governments, a move GM's CEO Ed Whitacre says signals the automaker is on the mend.

"Our ability to pay back these loans less than a year after emerging from bankruptcy is a sign that our plan for building a new GM is working. It is also an important step toward eventually reducing the amount of equity the governments of the U.S., Canada and Ontario hold in our company," Whitacre wrote in an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal.

GM got a total of $52 billion from the U.S. government and $9.5 billion from the Canadian and Ontario governments as it went through bankruptcy protection last year. The U.S. considered as a loan $6.7 billion of the aid, while the Canadian governments held $1.4 billion in loans.

The U.S. government payments, made Tuesday, came five years ahead of schedule. GM hopes to repay the remaining debt, which came in the form a large stakes in the automaker, with a large public offering later this year. U.S. taxpayers own about 61 percent of GM and Canadians own about 12 percent.

“Hopeless” and “really bad” are words Lutz used to describe both the products and many of the executives on hand when he joined GM in late 2001. “Every one of the cars that GM brought out for the first three years I was here … hopelessly failed,” Lutz said in a recent interview.

The problem, he says, was that a company that once rose to the top of the competitive automotive heap by producing the world’s best cars and trucks had settled into comfortable mediocrity. The situation was made worse by the false hope that GM could use the same marketing techniques that worked for consumer product firms such as Proctor & Gamble — whose former boss, John Smale, briefly served as GM chairman.

Unable to come up with products that would work, the company set up a think tank that operated like something Lutz calls, “a Romper Room,” throwing out wild ideas that seldom went anywhere. Those that did were largely disasters, like the ungainly Pontiac Aztek, a crossover whose big selling point was a pop-up camper that could attach to its rear.

Lutz was determined to fix that, something that didn’t always sit well with the likes of Tom Davis, the former GM product chief who called the decision to hire Lutz “a colossal blunder.” Davis left soon afterwards.

With former GM Chairman Rick Wagoner’s approval, Lutz shook up what was a house of cards. He demoted the marketers who thought they could tell stylists what to do, instead putting the company’s once-legendary designers back at the top.

“In the real world,” says Lutz, “the first gate (for a car buyer) is how it looks on the outside; the second gate is how it looks on the interior. Then, if they like it, they get around to looking at the cupholders and storage bins and everything else.”

Another major step was consolidating regional vehicle operations into one global product development system, says Lutz. That makes it easier to develop the products customers want, while keeping R&D and manufacturing costs down to a competitive level.

“Product is the royalty, in our business, and design is the king,” Lutz says, adding that, “everything else pales into insignificance.”

It hasn’t been an easy sell, he admits. He says the finance side of the business debates every penny. Lately he has been pressing them to add cost where he thinks it’s critical, such as interior design and electronic technology.

The new Chevrolet Equinox proves his point, he insists. Finance was convinced it wouldn't make money. Instead, the high-demand model is selling at a price several thousand dollars above the old Equinox, yielding much higher margins in the process.

That doesn’t mean simply throwing money at a project works, Lutz quickly stresses. “I’m greatly in favor of reducing cost where it doesn’t have any value to the customer.”

In a conversation shortly after joining General Motors nine years ago, Lutz said he was confident he could do the right things to produce better products for the company. “But my real legacy,” he said at the time, would depend, “on what happens after I leave.”

The good news, he insists, is that the new and leaner management system at GM seems to understand what’s necessary. That includes Ed Whitacre, the former telecommunications executive hired by the Obama White House as part of its bail-out plans for the company, post-bankruptcy.

Earlier this month, GM posted a net loss for 2009, but said it could still turn a profit this year. The automaker took in $1 billion more than it spent in 2009, a sign it was no longer bleeding cash. And it began 2010 with $36 billion in cash and $60 billion in debt, versus $14 billion in cash and $104 billion in debt when 2009 began.

Insiders question how well the two GM executives have gotten along. For the record, while they admit they didn’t work together very closely, they seem to have broad respect for each other. Lutz certainly has to hope that Whitacre’s team will follow the path the former Marine pilot blazed.

“The old, ossified General Motors culture is really dead,” says Lutz as he reaches for his Blackberry.

That, in itself, is a small measure of change. When the former Chrysler president arrived at GM, he didn’t even know how to use a computer, and would have his secretary dictate e-mails. These days, Lutz says he is likely as not to fall asleep with the little device in his hands.

With time ticking away on his career, he’s still got a lot to do, starting with e-mails.

Some of those missives are coming from outside. He’s got a book project well underway, a follow-up to his earlier, “Guts,” a perennial favorite among business readers. Lutz also plans to sign on with a few boards. And he’s considering opportunities to speak and write more regularly.

His father, he often notes, worked until just four months before his death at 94. Ever competitive, Lutz sees that as a goal to beat.