It's been 24 years since Halley's Comet last passed through the inner solar system, but remnants from the icy wanderer are lighting up the dawn sky this week in the Eta Aquarid meteor shower.

The meteor shower is predicted to peak early Thursday morning. Under ideal conditions (a dark, moonless sky) about 40 of these very swift meteors can be seen per hour.

The shower traditionally appears at about one-quarter peak strength for about three or four days before and after May 6.

The famous Halley's Comet takes roughly 76 years to circle the sun and last passed through our cosmic neighborhood in 1986. Halley's orbit closely approaches Earth's orbit in two spots, offering two chances each year to see meteor showers left over from the comet's cosmic "litter."

One point is in the middle to latter part of October, producing a meteor display known as the Orionids. The other point comes in the early part of May, producing the Eta Aquarids.

When and where to watch

There are, however, two drawbacks if you plan to watch for the Eta Aquarids meteors this year. [Meteor shower map.]

First, there is the moon, which is at last quarter on the peak morning and "muscles in" on the fainter meteor streaks by brightening the early morning sky with its bright light.

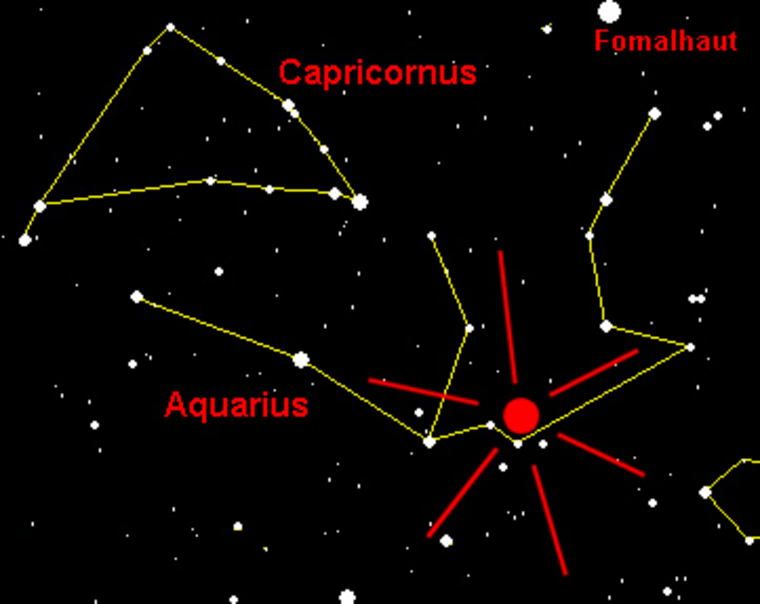

The other obstacle — at least for those watching from north of the equator — is that the radiant (the emanation point of these meteors) is at the "Water Jar" of the constellation Aquarius, which comes above the southeast horizon at around 3 a.m. local time and never gets very high as seen from north temperate latitudes. That means the actual observed rates are usually much lower than the oft-quoted 40 per hour.

In North America, typical rates are 10 meteors per hour at 26 degrees north latitude, half this at 35 degrees latitude and practically zero north of 40 degrees.

Conversely, those who live in the Southern Hemisphere, where Aquarius rises much higher into the sky, consider this to be one of the best meteor showers of the year.

Catch an Earthgrazer

For most, perhaps the best hope is catching a glimpse of a meteor emerging from the radiant that will skim the atmosphere horizontally — much like a bug skimming the side window of an automobile. Meteor watchers call such shooting stars "Earthgrazers." They leave colorful, long-lasting trails.

"These meteors are extremely long," said Robert Lunsford, of the International Meteor Organization. "They tend to hug the horizon rather than shooting overhead where most cameras are aimed."

"Earthgrazers are rarely numerous," cautions Bill Cooke, a member of the Space Environments team at the Marshall Space Flight Center. "But even if you only see a few, you're likely to remember them."

If you do catch sight of one early these next few mornings, keep in mind that you'll likely be seeing the incandescent streak produced by material which originated from the nucleus of Halley's Comet.

When these tiny bits of the comet collide with Earth, friction with our atmosphere raises them to white heat and produces the effect popularly referred to as "shooting stars."

So it is that the shooting stars that we have come to call the Eta Aquarids are really an encounter with the traces of a famous visitor from the depths of space and from the dawn of creation.