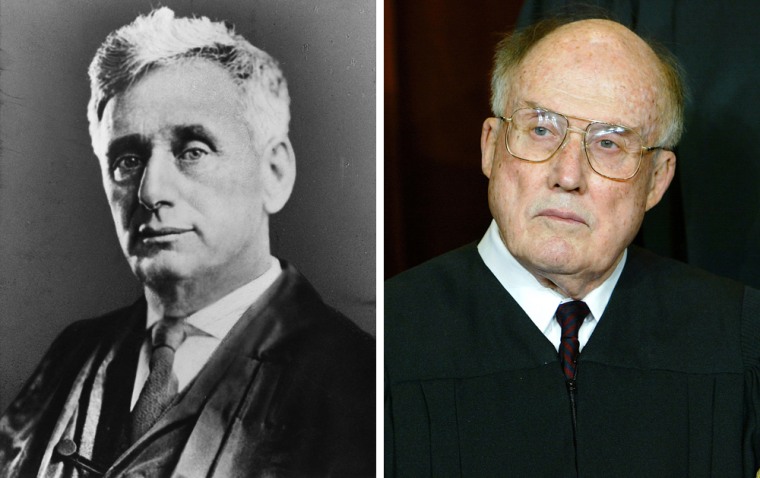

John Marshall, William Rehnquist, Louis Brandeis, Earl Warren, William O. Douglas, Harlan Fiske Stone, Robert Jackson, Felix Frankfurter, Joseph Story and Roger Taney.

This roster of Supreme Court justices — rated by legal experts and historians as among the greatest or most influential jurists in the court’s history — had one thing in common with Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan: None had ever served as a judge prior to becoming a justice on the nation’s highest court.

Every member of the current court served as a federal appeals court judge immediately prior to being appointed to the high court. And Americans have gotten used to thinking this is normal or even mandatory. It isn't. Forty of the 111 men and women to serve on the high court since 1789 had no judicial experience. In fact, it isn’t even required that a justice possess a law degree.

The issue is expected to be a point of contention during Kagan’s confirmation hearings, but isn’t likely to derail what looks to be her near certain confirmation.

Some Republican senators say Kagan’s lack of judicial experience is reason for concern. Senate Judiciary Committee member Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, called Kagan “a surprising choice because she lacks judicial experience. Most Americans believe that prior judicial experience is a necessary credential for a Supreme Court justice.”

(He’s right about public opinion: a Washington Post/ABC News poll last month that found that 70 percent of Americans favored a Supreme Court nominee having judicial experience.)

The increasingly powerful conservative leader Sen. Jim DeMint, R-S.C., said he was “concerned that she has no judicial experience to give Americans confidence that she will be impartial in her decisions.”

But no Supreme Court nominee has been defeated solely on the grounds that he or she lacked judicial experience. And with 59 Democratic senators, President Barack Obama almost certainly has the votes to get Kagan on the court.

Among the high court giants who had never served as a judge, Stone is famed for pioneering in 1938 the idea of the justices applying “more exacting judicial scrutiny” to laws targeted at particular religious, ethnic or racial minorities.

And Jackson’s three-part test for the constitutionality of presidential actions in wartime during the 1952 steel seizure case is among the most cited passages in all high court decisions — one that’s had special resonance with the court’s decisions on detainee treatment and other war policies since the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

(Justices are not required to have a law degree, but as a practical matter it has developed into a prerequisite. Jackson was the last justice to have “read law” by working as a clerk in a law firm rather than going to law school.)

Not since 1971 has the Senate voted to confirm Supreme Court nominees without judicial experience — Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist, both of whom were nominated by President Richard Nixon.

Historian David Yalof, the author of “Pursuit of Justices,” the definitive book on post-World War II Supreme Court nominees, said Powell and Rehnquist not having been judges “did not even come up as an issue” in their Senate hearings.

That was partly because both Powell and Rehnquist had won respect from their peers: Powell as a president of the American Bar Association and civic activist in Richmond, Va.; and Rehnquist as a conservative legal scholar and top Justice Department lawyer.

But in 2005, when President George W. Bush nominated Harriet Miers to the high court, her lack of judicial experience became an issue, though one that was largely a code phrase for other shortcomings.

Miers had never been a judge, but that was the least of her problems. Bush withdrew her name from consideration after a few weeks of embarrassment and growing opposition from social conservatives.

“There were people troubled by her law school pedigree,” Yalof said, referring to Miers’ alma mater, Southern Methodist University Law School. Bringing up her lack of judicial experience was one way to signal disapproval of her nomination “without appearing elitist,” he said.

Conservative groups, seeing Sandra Day O’Connor’s retirement as a once-in-25-years chance to re-orient the court, were appalled at Miers’ lack of intellectual firepower. While the right worked to scuttle Miers nomination, Democrats mostly bided their time, although they too saw her as mediocre.

The day after Bush announced the nomination, Connie Mackey, a Family Research Council lobbyist, said, “It takes a lot of steam out of the grass roots." Sen. Sam Brownback, R-Kansas, lamented that it was “a missed opportunity.”

Miers then flunked her initial interviews with Judiciary Committee members.

She blundered by first telling former Judiciary Committee Chairman Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, then a Republican, that she agreed with the 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision, which declared a right to privacy for married couples and was the cornerstone of the privacy rights later expanded in the 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion decision. Then she denied that she’d told Specter that.

Emerging from his interview with Miers, Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., portrayed her as utterly out of her depth, unready to give any views on fundamental Supreme Court precedents. “She is not a constitutional lawyer, she never purported to be a constitutional lawyer, but she clearly needs some time to learn about these cases,” Schumer said.

Such a fiasco isn’t likely to happen with Kagan, whom former Reagan administration solicitor general Charles Fried calls “a superb lawyer and an awesomely intelligent person.”

Given the record of non-judges such as Brandeis, Warren, and Jackson as influential justices, why has judicial experience become a favorite talking point for those opposed to a nominee, whether it is Miers or Kagan?

“It’s easy, it’s convenient, and it appeals to the public,” explained Yalof. Serving as a judge has become “a check-the-box exercise.” But he pointedly asks, “What does judicial experience really mean? Is there a minimum amount?”

John Roberts, for instance, served as a federal appeals court judge for a little more than two years before becoming chief justice. Clarence Thomas served on the appeals court for only a year and a half before joining the high court.

Legislation to require that Supreme Court nominees have prior judicial experience has been introduced, but has never gained traction.

And that’s a good thing, argued Supreme Court historian Henry Abraham.

“To raise judicial experience to the level of either an express or an implied requirement would render a distinct disservice to the Supreme Court,” he said.

That’s because, Abraham said, the Supreme Court isn’t a trial court, but a tribunal that chooses which cases it will hear and rules on the broadest questions of public policy. The skills called for are those of a savvy negotiator and consensus builder, such as Earl Warren, or master of ringing rhetoric such as Robert Jackson.

Those who expect or demand that a Supreme Court nominee must have served some time as a judge “ignore the rich history of justices with no judicial experience,” Yalof said.

With his choice of Kagan, Obama has confidently broken from the “check the box” mentality and reverted to the tradition of Jackson, Brandeis and Douglas.