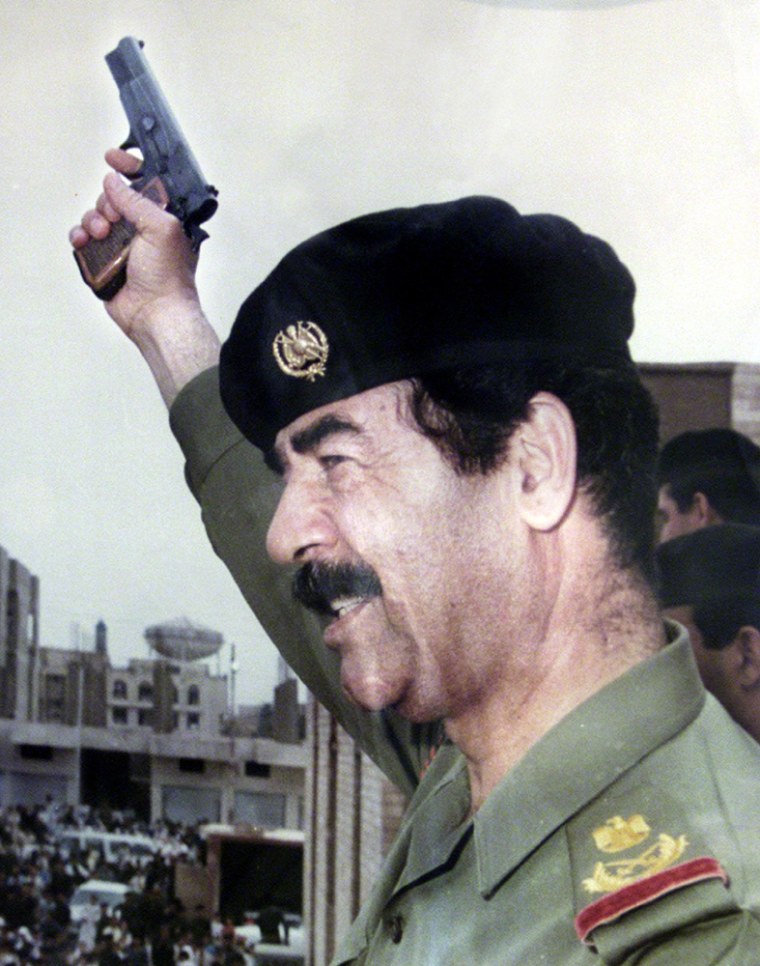

Saddam Hussein, the dictator of Iraq whose brutality and appetite for expansion ultimately drew his nation into direct conflict with the U.S. superpower, was captured alive in his home town of Tikrit, the head of the U.S. administration in Iraq said Sunday.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we got him,” L. Paul Bremer told a news conference. Bremer made that announcement in Baghdad, calling it “a great day” for Iraq.

From obscure party hack and torturer to president of Iraq, from Arab strongman and friend of the west to reviled dictator, Saddam dominated Iraq and repeatedly held the political agenda of his region for ransom. He built Iraq into the Arab world's most dynamic economy and then ruined it. He pitted his country against the world, building a unity based on terror and coercion. He invaded and laid waste his neighbors and massacred his own citizens. He built, he threatened, he destroyed, and inevitably he brought destruction upon himself.

Saddam reportedly relished his reputation for shrewd diplomatic brinkmanship and indeed bedeviled several U.S. presidents. But his miscalculations were titanic: using chemical weapons against his own population in 1988, launching a war against Iran in 1980 and an invasion of Kuwait in 1990. His final mistake -- assuming the United States would refuse to invade Iraq without U.N. Security Council sanction -- proved his undoing.

Born into a vacuum

Saddam was a product of his place and time, which was marked by poverty, struggle and a great deal of violence. He was born into an Iraq that was not a nation but merely a mass of human beings “devoid of any patriotic idea, … prone to anarchy and perpetually ready to rise against any government whatsoever,” according to the king of Iraq himself, Faisal I.

That was written in 1933, just four years before Saddam began life in a village outside the provincial town of Tikrit. With his father dead, he was not expected to go to school. But Saddam decided different: According to the dictator's own account, he found relatives willing to give him a pistol and send him off to school. It is a measure of Saddam that he believed that all he needed to equip him for an academic career was a loaded firearm.

But Iraq has always been a place where rivalry and the principle of vengeance promote violence.

Religion lies behind this instability, particularly the fear and distrust that can exist between Sunni and Shiite Muslims. The majority of Iraqis are Shiite, but minority Sunni Muslims like Saddam have long been rulers and administrators.

There are also other sizeable minorities who are disposed against the Arab Sunnis, mainly Kurds (who are Sunnis but not Arabs) and Christians. So the very makeup of Iraq contains the seed of rule by paranoia, terror and persecution. It only needs for the wrong man to grasp power.

A man with few limits

Step forward Saddam. From the beginning Saddam had allied himself with the Baath Party -- an ideology-driven political movement that borrowed from Arab nationalism and the methods of totalitarian communism, but in the end rejected all of those models. The Baath Party wanted to create a “New Arab,” and its method was extreme and pervasive violence. That suited Saddam, a man who had no concept of limits to behavior.

Saddam had been involved in an assassination attempt on the prime minister in 1959: He took a bullet in the leg and fled to Egypt.

After the 1963 coup that brought the Baath Party to power, he was back in Iraq, working as an “interrogator” at camps where the party held suspect elements. It was a theme that was to be repeated. In the coups and takeovers that followed through the ’60s and ’70s, there was purge after purge, in which not only the opposition but hundreds of leading party men and their families died. Like Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union, Saddam was the purge-master.

Those who did not die in the torture chambers were exiled and often assassinated abroad, in the Arabian Gulf or even in London.

Saddam controlled Iraq's security agencies from the early 1970s, and he was certainly behind these killings. From around 1975 he could be considered to be in complete control of Iraq, although he did not take formal charge of the presidency until 1979. By then he was more secure: secure enough to widen his concerns. Killings and deportations of northern Kurds and southern Shiites had begun as soon as the Baath Party took power, but now they intensified. Kurdish towns were razed; Shiite populations were deported to Iran, while leaders and clerics were executed or “disappeared.”

Taking power

Some puzzled at how a man who created so much hatred -- it is documented by Middle East Watch that Saddam arranged the torture of children to extract adult confessions -- could possibly survive. The answer is to be found in Saddam's grasp of the mechanics of terror. He knew when to kill his enemies and when to compromise them. In the purge that followed Saddam's final assumption of the presidency, for example, ranking members of government were arrested not in secrecy, but at public meetings. And then their colleagues — ministers and party leaders — were ordered to make up the firing squads. They were made part of the terror. In the words of Iraqi author Samir Al-Khalil, Saddam institutionalized fear, while “character and personality shriveled up.”

But Saddam's story has much more to it than pure terror.

Saddam was a worker, and he was utterly meticulous. He worked 16-hour days for years on end. He never forgot a detail. Even his enemies testified to his astonishing energy and application.

Developing Iraq

From the mid-1970s, he channeled some of this energy toward the development of Iraq, a country where oil and agriculture could work together to create the most dynamic economy the Arab world has ever seen. Saddam built infrastructure and industries; he developed the cities and enriched the farmers. And for many this seemed like the successful secular state that the liberal Arab middle class had always dreamed of: There was education and advancement for all who did not threaten Saddam, including women, who entered the professions in huge numbers. This triumphant development was one of Saddam's routes to leadership of the Arab world.

The other was firepower. In the early 1970s, Saddam had already begun a covert weapons program, using oil money to attract Arab technologists from all over the region. All he needed was willing collaborators in the West. And he found them.

At first the key was Moscow. While the United States had given some intelligence support for the Baath coup plotters in 1968, the armaments the Iraqis wanted were not forthcoming, so the new government turned at once to the Soviet Union, which had no inhibition about rearming the Arab world. It was an alliance of convenience, since the Baath Party was virulently anti-communist. But by the time that Saddam had levered himself up to effective control of the regime, the Moscow link had also become Saddam's guarantee of Western cooperation. So states like the United States, Britain, France and Germany competed to supply him with the technology to construct an arsenal of mass destruction.

The only check came when Israel destroyed the nuclear reactor that the French had sold Saddam. Even then, the West was unworried, for there were new reasons to back Iraq. Saddam's weapons were now pointing at Iran, the revolutionary Islamic state that had become the great strategic threat in the region. The war Saddam started with Iran lasted almost a decade, and all the while the United States and Europe fed Saddam with arms and stood by as Iraq (and Iran) repeatedly used chemical attacks to intensify a slaughter that gained both countries precisely nothing.

A regional bully

Or less than nothing, for the war had left Saddam short of money. Always suspicious of his army, like all dictators he had to occupy the military with victories. A new genocidal campaign had already begun against the Kurds of northern Iraq -- a campaign called, significantly, Anfal, meaning “booty.” But here Saddam made a mistake, when gas attacks on Kurdish civilians finally alerted the world that he was now out of control. Another mistake followed, and much more serious: Saddam sent the army to invade Kuwait, a prize that gave him, briefly, control of almost half the world's oil.

Overnight Saddam became the world's criminal, and the long endgame had begun. Within six months he had been kicked out of Kuwait by a U.S.-led invasion, his army broken and humiliated, while the northern Kurds and southern Shiites were in open revolt. He looked finished, but he was only caged, not killed. Just as the hugely destructive war with Iran had been used as a unifying principle, now it was the crushing of the Kurds and the Shiites that became the motivator. So even when the United Nations fenced off part of northern Iraq as a Kurdish safe haven, the persecutions on Saddam's side of the border continued. And 10 years of U.N. sanctions gave Saddam a new opponent to occupy his army and his people.

Sept. 11, 2001, changed Saddam's world -- only he did not know it. Surrounded by half-deranged family members and frightened henchmen, Saddam continued to act as if there were no limits. In fact much of the world was now ready for the readmission of Iraq to the normal world, on normal terms -- Saddam could have come to terms with the U.N. arms inspections forced on him by the United States and its allies, but he didn't. He didn't understand the need for limits.