Catherine, a recruiting specialist, was out of work for nearly a year when a friend sent her a job opening listed at Vault.com. Ready to try almost anything, she quickly responded to the ad and e-mailed her resume, applying for a position as "correspondence manager."

And just that quickly, she became an unwitting member of an Internet scam that's being blamed for a half billion dollars in attempted thefts from U.S. firms during the past 18 months. The crime has Internet merchants, along with the FBI and U.S. Postal Inspection Office, fit to be tied.

Within days, before Catherine even knew she had been hired, packages containing a digital camera and a computer monitor arrived at her door. Her instructions were simple: repack the items and ship them to an address in Russia. For her trouble, she would earn 13 percent of the sale price. It seemed reasonable enough, so she sent the package along.

Days later, she got a phone call from a man who said he was told to wire $10,000 into her bank account.

"I had no idea what he was talking about," she said.

Her caller was an eBay.com user, who had recently won the bidding for a classic electric guitar and then been told to wire the large payment to Catherine. She was then instructed to move the money overseas, to an account controlled by her new boss.

Catherine knew right away something was terribly wrong. She called the FBI, which informed her that she'd unknowingly helped a global crime ring. An agent then told her the FBI had an ongoing investigation into the crime ring, and asked that she "play along" with the con artists for a while in an attempt to unearth more information about them.

Within a week, dozens of packages and wire transfers were headed Catherine's way — some $35,000 in money and merchandise in less than 10 days.

"These people are very, very organized." she said.

Out of control

Catherine had unwittingly signed up to be part of a new scam that's raging on the Internet, dubbed "postal forwarding," or "reshipping fraud" by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. According to authorities, thousands of job seekers have been caught up in the con.

"It's out of control," Barry Mew, spokesman for the Postal Inspection Service, said. "My phone rings off the hook. ... There are hundreds more like (Catherine)."

At best guess, Mew said, the con artists have already made off with between $5 million and $10 million. One major credit card company has seen losses of $1.5 million to the scam, and a payment processing company for an Internet site is out $1 million, he said. Mew declined to name the companies.

Some of the recruited helpers are losing big money, too, Mew said. One woman passed on $25,000 to Eastern Europe before she caught on to the con. When one of the victims who sent money to her stopped payment on his $2,500 check, his bank withdrew the money from her account — leaving her with a $2,500 loss. She had to sell a mutual fund devoted to her child's college education fund to cover the loss, Mew said.

FBI spokesman Paul Bresson said he couldn't comment on specific investigations, but that the agency did have ongoing investigations into reshipping frauds.

"This is something we are familiar with," he said.

During a sweep of Internet-related arrests announced last month by the FBI, the agency issued a warning about reshipping schemes. As part of that warning, the Merchant Risk Council, a non-profit organization created by a consortium of electronic commerce firms, released the results of a 120-day study of fraud at the top eight Web retailers.

The council found 5,000 consumers had participated in the scam from July to October, enabling con artists to steal $1.7 million from those eight sites during that 120-day period. A host of other fraud attempts were stopped by the sites. Total attempts to steal merchandise using the reshipping scam add up to an estimated $500 million, said Susan Henson, spokeswoman for the Merchant Risk Council.

"This is a huge crime," Henson said. "It's phenomenal. It's been hovering under the radar a bit, but it's giant."

The elaborate scam is a mixture of credit card fraud, identity theft, and auction fraud. The Net of victims is wide, ranging from eBay auction winners, to credit card firms, to major online retailers. Catherine said she received packages purchased from Amazon.com with stolen credit cards.

Amazon spokeswoman Patty Smith denied the scam had hit online retailer very hard.

"This really isn't a big issue for us," she said. "Our fraud detection systems are sophisticated enough ... to catch these kinds of things."

But Jonathan Lane, a fraud investigator for online retailer PCMall.com, said major Internet retailers are indeed being hit by the scam.

"There's a substantial number of merchants involved," Lane said.

Ads all over the Web

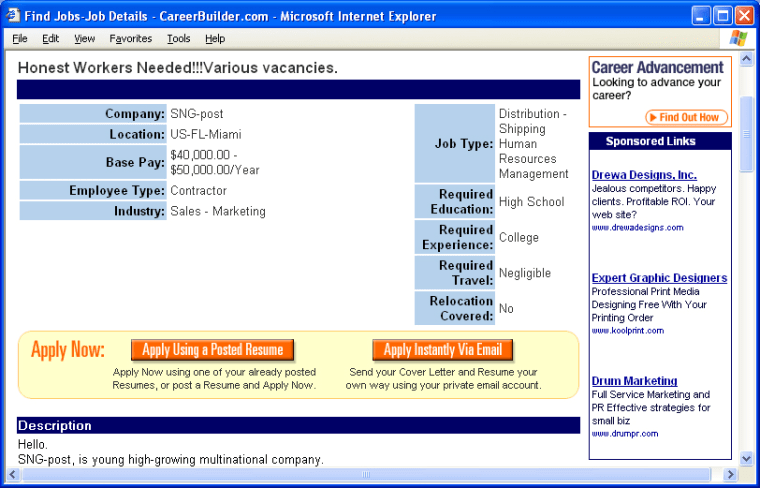

It starts with hundreds of recruiting advertisements on job sites like Monster.com and CareerBuilder.com. At any given time, Mew said, he can spot ads on 25 different Web sites. Other victims have been approached in Internet chat rooms and pointed directly to the fraudulent company's Web site, where the job postings are listed.

The help wanted advertisements are innocuous enough.

"Our company is engaged in correspondence managing, distributing different goods worldwide, buying and reselling these goods," says one version of the ad, which appeared on CareerBuilder.com for about a week, until it was removed after MSNBC.com brought it the Web site's attention.

The ad explained the need for U.S-based employees to ship products overseas: "Everybody knows Russia is a part of Europe, but most of foreign people are afraid to have business with {sic} country ... We would like to prove our respectableness, but when we communicate with people from other countries they can't avoid stereotypes. So, we are looking for the persons who can represent our company in his country. Their duty will be to accept money and different goods, because often people don't want to send money to my country."

Put simply, the employees are used to move merchandise or money out of the United States. But behind the scenes, the organized crime ring is using a variety of confusing tactics.

One flavor of the scheme is designed to circumvent fraud protections at mail order companies and Web sites while stealing popular items such as handheld computers, digital cameras and DVD players. To avoid raising suspicion, the con artists make sure the shipping address -- the address of the "recruit" -- is in the same state as the billing address on the stolen credit card. To do so, the con artists have a wide variety of employees and stolen credit cards to choose from. They have also managed to change billing addresses on stolen credit cards so they match the recruit's locale. Some 1,300 accounts were updated with new billing addresses at one credit card company victimized by the con artists, Mew said.

Auction bidders, such as the man who was trying to purchase a $10,000 classic guitar, are also targeted. Con artists impersonate a recruit and place auction items for sale. They then tell the winners to wire funds to the recruit's U.S. bank account, avoiding any suspicions aroused by the mention of overseas wire transfers. The recruit, of course, is then instructed to wire the funds overseas.

Enticing terms

The homebound are at special risk of being caught up in the scam, said PCMall's Lane.

"When the recruits are Social Security recipients, people on disability, single parents, and unemployed people from coast to coast, it's a story that hits pretty hard," he said.

Not every recruit catches on as quickly as Catherine. One California recruit sent 750 packages — average value, $1,500 — to Russia between October 2002 and March 2003, Mew said.

While often not legally guilty of theft, recruits are often guilty of falsifying government documents, as they are instructed to declare the packages as "gifts" on Customs forms. They might also be guilty of income tax evasion, Lane said. And then there's the humiliation.

"Not only was I arrested for theft by receiving," one anonymous victim posted to a Web site, "[I] lost my computer, my dignity, the humiliation, my dog went to the pound, had to bail him out to! Attorney cost $2000.00," he wrote. "I was only involved with them for 3 weeks before I was arrested and I only made $200.00."

Recruits are also at risk of identity theft, since they usually give the con artists their bank account information and other critical data while signing up for the job. A victim named Brenda said that after she realized she'd been scammed, and went to the police, the con artists threatened her.

"These people have my identification; Social Security Number, address and handwriting sample," she said. "Since this investigation began, I have received emails that state 'I KNOW WHO YOU ARE.' I fear for the safety of myself and my family." She eventually moved, believing she wasn't safe at her old address.

Catherine said she received calls from dozens of angry auction winners as she played possum for the FBI. When she tried to explain she was an unwitting character in the con, many didn't initially believe her.

"I was getting threats from people saying, 'I'm going to sue you,' " she said. "It's surreal. You're sitting here looking for a job, and all these thousands of dollars are slipping through your hands." Her bank ultimately accepted about $4,000 in wire transfers, even though she told the firm to reject all wire payments. Meanwhile, she lost the $108 she spent shipping the initial package to Russia. She also learned a disturbing lesson about human nature when she sent an e-mail to all her 17 "co-workers," warning them that the job was really a scam.

"One guy wrote, 'I don't care where the money is coming from,' " she said. "It's amazing this person wrote this to a stranger. The FBI's going to take a look at him."

Pam Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum, said she has been studying the growing help wanted scam for several months. It works because unemployed people are vulnerable and an easy target for con artists, she said. One victim she spoke to "had been out of work for a year. That's a common factor," Dixon said.

"We are capable of extraordinary rationalization" when unemployed, she said.

Making matters worse, online job sites often give users a false sense of security, Dixon said, because consumers have the impression the ads have been vetted by the site -- as newspaper classified ads often are. What's more, many surfers arrive at CareerBuilder.com by clicking "help wanted" buttons while browsing local newspapers online, as the sites act as the employment section for hundreds of newspaper Web sites around the country. CareerBuilder.com is owned by newspaper conglomerates Gannett, Knight-Ridder, and The Tribune Company.

"I believe there's an implied trust when job seekers go there," Dixon said.

Jenni Sullivan, a spokeswoman for CareerBuilder.com, said her company has employees who regularly review job listings on the site for fraud.

"Customer service representatives use different search methods. ... They continually monitor the site and if they come across anything suspicious they take immediate action," she said. "This is not as prevalent as I believe other people are saying it is. We haven’t seen an indication that there’s been a rise in this activity (at CareerBuilder)."

Monster.com spokesman Kevin Mullins said some of the fraudulent ads have been placed on his company's site, but said their appearance is "rare."

"Most often we take the job down within a couple of hours," Mullins said.

The use of fraudulent postal forwarding companies in a scam was first chronicled in April by MSNBC.com, but there is evidence the crime rings has been operating since April 2002, Lane said.

Mew said said he's not optimistic the criminals will be caught any time soon; only consumer education can even slow them down.

"We need to educate the masses. There’s no job at home receiving and forwarding packages," Mew said. "And there's no job sitting at home receiving money and sending the money to Eastern Europe. People like to think there are jobs like that, and that’s why it's so successful."