The worst part of any vacation is coming home. Not just because your fleeting glimpse of freedom is finished, but because you've got to pay the absurd phone bill you racked up while you were gone. Ugh. Why?

If you travel a lot, you know the drill: For every call you make, text you send, or bit that you download overseas, you pay. A lot. More than seems possible. There are special travel packages available to ease the pain a bit, but if you're a regular traveler, your telco will always be there to welcome you back home by heel-kicking you in the teeth, monetarily. We're talking $3+ a minute to place calls, international or otherwise, and $10 per megabyte data charges.

So what is it? Price fixing? Excessive regulation? Actual expenses? Why on earth does it cost 20 times more to visit a webpage on your smartphone on one part of the planet's surface over another? The reasons are complicated, but don't abandon all hope — yet.

How roaming works

Before you deplane in a given country, there's a good chance that your cellphone will have found its way onto a native network. You may get a text message saying you're now on your carriers' foreign partner, or maybe not. You may have had to notify your carrier of your trip overseas to get service, or maybe not. Point is, it's very easy to use your phone in another country, and there's almost no functional compromise in doing so: the number is the same; you can still send texts; connecting to the web works just as it does at home. Magic.

Behind the scenes, things are a bit more complicated. A call consists of two parts—the voice or data transmission, and then an accompanying signal transmission. Only if you're overseas, that signal transmission travels a lot farther than the rest of the call. Say you're in London, and you're meeting a friend for dinner. You need to call him.

If you're using a British-bought phone, this is what happens: Your phone will transmit a signal transmission to your carrier, which includes information about the phone, length of call, destination number and geographical location.

This signal is passed along to the recipient's phone as well, to identify the caller. Your phone will transmit a voice signal to your carrier, which is then routed to the recipient's carrier, and then to their phone. The call is connected, the carrier knows how much call time you've used, and you're charged according to your contract—the one you signed when you got your phone, or a special one you agreed to before travel.

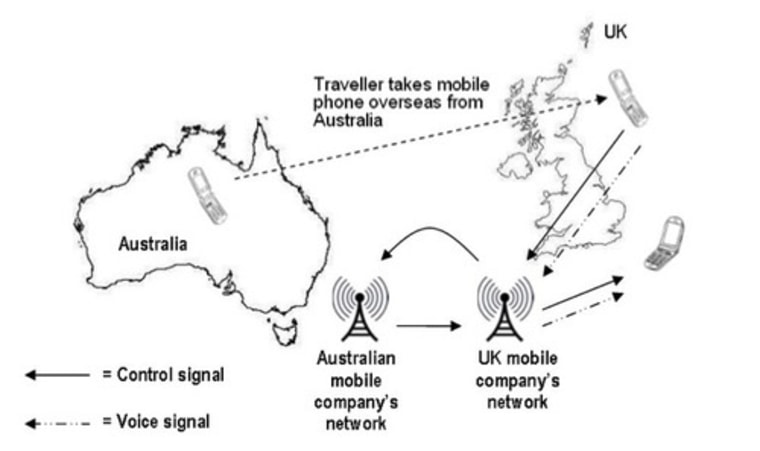

But let's say you call your friend in London from your American phone, on, say, AT&T. Here's what happens then: Your phone transmits a signal transmission—location, length, destination—to the local carrier of your provider's choice. The local carrier passes the signal transmission overseas to AT&T, which passes it back to your recipients British carrier, and then to his phone. The voice signal travels straight from your new British carrier to your recipient's British carrier. The chart above outlines a similar scenario, with an Australian visitor in the UK, via .

In other words, while your voice never leaves your host country, because of the signal transmission, every call you make abroad from an American phone is an international call.

Why it costs so much

From a technical perspective, making a call abroad is more complicated than making one at home, but not drastically so. It's when you start looking at the business arrangements that things get truly inscrutable.

International roaming is built on a shoddy patchwork of contracts, negotiated on a carrier-by-carrier basis, totally out of view. If an American carrier wants to make sure its customers can use their phones all over the world, they need to ink separate contracts with dozens—if not hundreds—of carriers across the globe. If you place a call in another country, what you pay is based almost entirely on what the native carrier has decided to charge your carrier rent access. Try a Google search for "roaming agreement." So many deals!

You might think these detailed, one-on-one negotiations would help keep costs down, and that foreign carriers would be fighting for contracts with large American carriers by undercutting one another. A more cynical person might imagine telcos paring up and scheming to charge each others' customers sky-high prices. The truth is somewhere in between.

I talked to James Person, COO of the , which, along with the GSM Association, provides carriers rough outlines for international roaming, from how to deal with the logistics of passing along a call, to how to handle behind-the-scenes billing procedures. "With outbound roaming, those operators would like to provide roaming to you—that's a customer service." AT&T wants its customers to be able to use their phones overseas, because that's what people expect nowadays. It's perceived as part of the deal.

But despite the fact that they're the ones who send you your bill at the end of the month, companies like AT&T and Verizon don't make much money on your calls. Most of the technological legwork falls to the host carriers, and after the relatively modest interconnection and signal handoff costs are covered, they can charge as much of a premium as they want:

"Everything they get from [a guest user] is just gravy. It's a convenience, often paid by the companies sending employees to use their numbers abroad. [A host] carrier looks at you as part of their profit center. There's no strong guidance for them to give you a good rate." In fact, quite the opposite. It makes sense for a foreign carrier to gouge American carriers and consumers. It's just good business, and adds up to serious money. By the time your carrier has finished paying its foreign partner, they already look like they're ripping you off, so there really isn't a whole lot of room to charge customers more. You carrier makes money on your roaming calls, sure, but they're not the reason it hurts so much. Not directly.

It gets worse: The one force that should keep prices down — competition — often doesn't exist. Many countries have highly regulated or monopolistic wireless providers, meaning that an American carrier looking for a partner might just have one or two choices. Throw in the fact that said country might not support the America carrier's wireless standard, like Verizon and Sprint's CDMA or AT&T and T-Mobile's GSM, and there aren't many options. Imagine a foreign carrier looking for a partner in the US. If it's a GSM carrier, it'll have to settle on AT&T or T-Mobile. That's just two choices, in one of the biggest countries on Earth.

The way this balances out, naturally, is with American carriers charging sky-high fees to foreign carriers for their visitors. (If a UK carrier wants to charge $2 a minute to route a call from an American phone, then they shouldn't expect a better deal when the tables are turned.) But while this provides broad balance for the businesses, you, Phone-Using Human, are only interested in the half of the arrangement that concerns you. So from a customer's standpoint, we're all screwed. You're better off buying a cheap pay-as-you-go phone as soon as you land, just so you can use the same networks your American phone would have connected to. Or, you know, just staying home for a week. Your kids will understand.

Are things going to get better?

Not for for a while. Researching this piece, I found dozens of by government agencies, domestic and foreign, fretting about egregiously high international roaming charges and lack of transparency. In the EU, where corporations in member countries answer to a central regulatory agency (the European Commission), international roaming charges have actually been capped, at least in Europe. (Outgoing voice calls are currently capped at .43 Euros a minute, which will fall to .35 in 2011.) Here's how the EC the roaming problem in Europe:

• EU roaming markets are imperfectly competitive,

• Pricing practices are not transparent. Customers' awareness of billing (whether they will be billed per second or per minute) and additional charges (such as taxes or fees) is severely limited,

• Retail charges are excessive due to the high wholesale charges levied by visited country operators and also, in many cases, from high retail mark-ups imposed by home network operators,

• Reductions in wholesale roaming charges are not passed through to customers in the form of cheaper retail charges

These are exactly the same problems American cellphone users face. We're charged incredible rates to use our phones abroad. It's not clear how severe the charges we're racking up are until it's too late. Prices, whether caused by carriers domestic or foreign, are high. In the EU, reports like this end with action. Elsewhere, they tend to end with a consistent conclusion: There's nothing we can do.

EU-style caps on American roaming charges may sound attractive, but who could demand and enforce them them? What governmental or non-governmental body could regulate that? The FCC? Some UN commission? "No body that could do that," Person says, "most of the solutions to resolve any pricing issues are done through the market, and through competitive means." So that's that. We are, and have been, at the mercy of the market.

Our best hope for cheaper international roaming is a fundamental change in how cellphones work, which, thank God, is starting to happen; Person sees prices falling as mobile carriers switch more and more to data-based tech, like VoIP. Skype's able to route calls overseas for almost nothing, so if all a host carrier has to do is connect visitors to an active data connection, their job gets simpler. Deals could be renegotiated as an industry is fundamentally changed.

Even further, you may not need to worry about who's supplying your wireless connection, or if it's associated with a particular number. You'll just rent a dumb data pipe with a throwaway SIM card, use your email, Skype, Facebook and IM accounts, and never worry about whether or not your phone number works. (After all, it's just another username, right?) But that dream is a few years away. Our phones are still locked, and most pay-as-you-go deals across the world aren't built around that kind of data traffic.

For now, the only relief we can expect will come by way of international roaming hubs, which both the CDMA and GSM trade groups are attempting to organize. This way, carriers negotiate with multiple carriers at once, in a sort of inclusive package deal. Instead of 20 contracts for East Asian roaming, a carrier could negotiate with multiple carriers at once, and sign a single, uniform deal. In theory, taking part in something like this would give a host carrier a guarantee of tons of new customers, giving them the scale to bring prices down. In practice, who knows?

Until then, and probably after, our vacations will follow this familiar template: A blissful stretch of denial, followed by crushing bill shock.