"We regret to inform you, that we were unable to charge your card," the e-mail begins. "Click here to continue payment verification process."

Is it real, or a fake? Should you fill it out, or delete it? The question seems to be vexing more Internet users every day.

E-mail inboxes are now flooded with such tempting messages, which often turn out to be "phishers" -- identity theft attempts disguised as helpful e-mail from a big Internet site. Some 60 million of the scam e-mails were sent out during one two-week stretch of December, according to the Anti-Phishing Working Group, a non-profit group of financial companies and Web firms studying the trend.

Ninety different versions of the scam e-mails appeared in November and December and now there are about five new attempts every day, the group said. Earlier this month, a phish campaign aimed at Citibank users led the company to actually issue a statement declaring it a fake. U.S. Bank issued a similar warning on Monday, after it was targeted by flurry of fraud e-mails. Ten different scams hit its customers during the past few weeks, the bank said.

The targets are global, too, ranging from the Bank of England to Australia's Westpac bank. UK-based NatWest was hit so hard in December that it was forced to temporarily take down its online banking site, according to published reports.

Making matters worse, virus writers have taken up the tactic as well. A virus released last week promised to add 10 percent to any recipient's PayPal account, if the potential victims filled out an accompanying form. They were also urged to click on an unsafe e-mail attachment named PayPal.exe.

"Registration is simple," the e-mail said. "Just unpack the attachment with WinZip, run the application, and follow the instructions we have provided."

Hard to ignore

When an e-mail arrives that appears to sent by a company consumers often work with, it's pretty hard to ignore, and many consumers don't. Up to 5 percent of recipients respond, according to the Anti-Phishing Working Group.

"Some of them are really, really good," said the group's chairman, Dave Jevans. "That's why people fall for them."

The notes appear to be personal, referencing an open account at a bank or Web site, but they are really just spam. Sent to a wide enough audience, an e-mail referencing Citibank or eBay will hit plenty of people who really are account holders.

Answering that e-mail can have devastating consequences, and virtually assures victims will face identity theft. Earlier this year, with thousands of victims piling up, the Federal Trade Commission and Earthlink issued a warning about this trend in scamming, and experts offered tips for consumers to tell the real firms from the con artists. PayPal, the most frequent target of the scams, has an advice page on its Web site designed to keep users from falling for the trick.

Confusing instructions

But many of the suggestions made to consumers are confusing, or even contradictory.

The "phishing" e-mail quoted above, for example, uses a tactic that flies in the face of one oft-quoted suggestion. For years, consumers have been told to look in their Web browser's address window to know if a Web site is real or an imposter. An address that seemed suspicious -- perhaps it begins with a numeric address, like 211.154.171.106, or has a series of stray characters in it -- was a sure sign of trouble, suggesting to users they've landed in a bad place. But a simple address, like WWW.MSNBC.COM, was considered a green light.

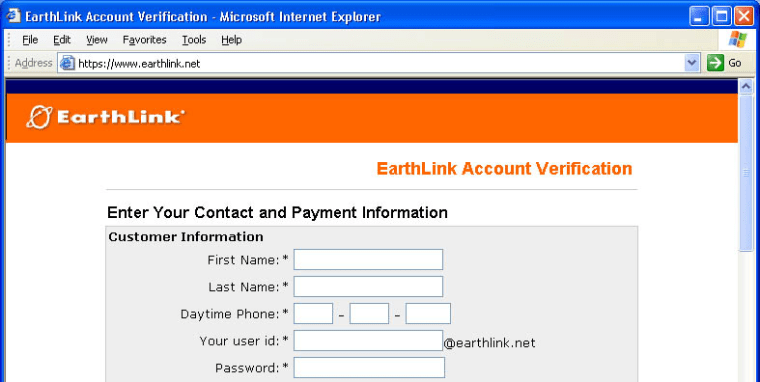

Not any more. A flaw found in Microsoft's Web browser last month lets computer criminals place just the right text up in that address bar, foiling that piece of advice. Users who received the e-mail quoted above and clicked on the link were delivered to a Web page that indicated it was www.Earthlink.net. An absolutely perfect imposter of the real Earthlink, the site sat on a Web server in China and was designed to steal debit and credit card numbers.

Another new version of phishing also preys on people's training to simply watch the address bar before they enter data into a Web site. In this variant, potential victims are directed via e-mail toward a company's genuine Web site, and then presented with a pop-up window to log in. Information typed into the pop-up box is sent to the computer criminal. One recent version sent recipients to the real Citibank site, but then tricked recipients into entering account information into the pop-up box.

"There's no way to tell (it's a scam). There's no address bar up there," Jevans said.

Real e-mails look like phishers

Other common advice, indicating that legitimate Internet companies would never solicit personal financial information in a generic e-mail, doesn't always apply, either. Internet service providers often send e-mails warning customers their credit cards have expired, requesting updated payment information. In other cases, Web companies have sent out marketing solicitations which appear similar to phishing e-mails. In one recent example, PayPal sent out a pitch to customers urging them to apply for a new PayPal-branded credit card.

"For complete pricing information and important terms and conditions, click here," the note said, listing www.PayPalCreditCard.com as the destination. Recipients complained that the e-mail looked like a fake. Adding to the confusion, it appeared to violate a policy posted on PayPal's Web site that urges users to disregard any e-mails which claim to be from the company but do noWhen security researcher Rob Adams forwarded the message to PayPal's special fraud alert e-mail address with a complaint, the company's Protection Services Department accidentally sent an automatically-generated response indicating it was a fraud.

Incidents like these make it even harder for consumers to tell legitimate e-mails from frauds, Adams said.

"PayPal isn't helping," he said.

No easy answerTelling fake e-mails from fair "requires a lot of diligence on the part of the recipient," said computer security analyst Mary Landesman. "Users should consider any site requesting personal financial information as suspicious until proven otherwise. Though in this particular instance, "PayPalCreditCard.com" happens to be legitimate, it would be trivial to create a site that looked every bit as convincing and use it to procure Social Security numbers and other private information."

At the core of the phishing problem is a new kind of identity theft experts are calling "corporate ID theft."

Criminals are increasingly aware of the power that trademarks have over consumers, said Federal Trade Commission lawyer Eric A. Wegner. Users have been trained to only trust well-known Web sites, Wegner said, and now, the criminals are using that trust against consumers. Whether it's an e-mail with an eBay logo, a Web site with Earthlink's name, or a Web site using an address that seems to be a legitimate brokerage, con artists are successfully using these trademarks to trick consumers.

One-by-one, tips consumers have been given to avoid getting scammed are being rendered useless by quick-to-adapt criminals, Wenger said. He is now groping with precisely what advice to give Internet users to avoid becoming ID theft victims. Today, the