This report aired Dateline NBC Sunday, June 27, 7 p.m./6 C. Watch more Web-only videos, including surviving soldiers describing the battle, here.

DAVE BROSTROM: When you send your son off to war, you expect that they will get everything that this great country can provide to protect them.

CARLENE CROSS: This situation was pure recklessness. You just have to say, "This is wrong.”

KURT ZWILLING: Bad things happen in war. But our boys are not cannon fodder. The United States has to protect these men. And, in this case, it was not done.

Every parent who sends a son or daughter to war knows the worst can happen. But that deep, often unspoken fear is tempered by a faith that the military won't needlessly risk the lives of their loved ones.

MARY JO BROSTROM: Your son takes off. But, he's coming home. I never imagined that he wouldn't. I always thought that Jonathan would always be coming home. He was Jonathan.

Jonathan — Jonathan P. Brostrom, a 24-year-old Army second lieutenant from Honolulu, Hawaii.

DAVE BROSTROM: He was your typical American boy. Very athletic. Had lots of friends.

You might say the Army was in Jon Brostrom's DNA. His father, Dave, was “Army strong” long before the ad campaign.

DAVE BROSTROM: It's a great institution. I spent my whole life in the Army.

Dave Brostrom was a career officer who retired as a colonel after 30 years. When Jon was in high school, the Brostroms moved to Hawaii. It proved a tropical paradise for an adventurous kid.

MARY JO BROSTROM: He loved surfing, golf.

One of the great joys of Jonathan’s life was his son Jase, who lived with his mother on the mainland. Jon loved to surf with his boy.

At the University of Hawaii, Jon joined Army ROTC. His parents were with him every step of the way.

DAVE BROSTROM: You know, he grew up as a military brat. I think he – he tried to follow in my footsteps. Made me very proud.

Jon volunteered for the infantry. That choice surprised his parents, especially Dave, a helicopter pilot who had commanded an aviation battalion in Desert Storm.

DAVE BROSTROM: When he said, "I'm gonna be in a – infantry," I kinda cringed.

MARY JO BROSTROM: We tried to talk to him out of it.

RICHARD ENGEL: So, he wanted to be in the fight at the front line?

MARY JO BROSTROM: At the front.

After being commissioned as a second lieutenant, Brostrom was assigned to the 173rd Airborne. His dad pulled a few strings to get him into the elite paratrooper unit, which was commanded by an old family friend. In the fall of 2007, the newly minted officer was sent to Afghanistan.

DAVE BROSTROM: He called and said, "I got my platoon." I was excited, because that's where you start your career.

In Afghanistan, Brostrom's platoon quickly warmed up to him. There was pride in the unit – it was called “Chosen Company,” but the soldiers call themselves “the chosen few.” The platoon was part of a front-line unit. His men all enlisted to see action.

And in today's “see-all-that-you-can-see” You-tube Army, they documented themselves in Afghanistan at work:

SOLDIER: Just another day at the office…

And at play:

That's Pruitt Rainey of Haw River, North Carolina – an all-state high school wrestler, training to be a mixed martial artist. Rainey impressed his unit early on with his strength, and his uncanny gift for poker, a game he learned from his father.

FRANKIE GAY: When he wasn't fighting or wasn't on duty, he was playing poker. He would actually call me during the games so I could talk with some of the other guys.

Jason Bogar, quieter and more introspective than most of his comrades, was on his second Afghan tour. He'd also served in Iraq and done hurricane relief in New Orleans. An accomplished photographer, Bogar e-mailed his photos and videos to his mom in Seattle.

CARLENE CROSS: Incredible pictures of the people and the surroundings. He would put these videos together with music and they were incredible.

Some of the videos gave an idea of how tough life was in the Afghan Mountains for Lt. Brostrom's men.

Comic relief was provided by a genial born-again Christian from Tennessee named Jason Hovator. According to his sister, he had always been funny.

JESSICA DAVIS: He was the life of the party. If you weren't his friend, then you wanted to be his friend. Because, he – he would make everybody laugh.

In the close-knit family of Second Platoon, Gunnar Zwilling was their little brother.

KURT ZWILLING: He was there for one reason. He was there for his guys. They were as close as I was to him.

His dad said his son was thrilled to be part of Chosen Company.

KURT ZWILLING: When you live with somebody and go through as much as they go through together, you learn to – to love each other like brothers.

Brostrom's platoon was based in mountains that cover the provinces of Nuristan and Kunar. The area was mainly controlled by insurgents.

DAVE BROSTROM: I knew that he was probably in firefights. But, he didn't – when he called us, he didn't – he didn't talk about any of that.

MARY JO BROSTROM: Our conversations were short cause when he would call, he was always busy: "I'm busy. I gotta go. I just want you to know that I'm fine, you know? Love – miss you guys. I gotta get back to the guys."

RICHARD ENGEL: No indications that he was in danger? He seemed calm and excited about the mission?

MARY JO BROSTROM: No.

DAVE BROSTROM: We were happy and proud. We still did not know what was going on.

Jon Brostrum wasn't telling his parents how dangerous Eastern Afghanistan really was for him and for his men.

BRIAN HISSONG: It was basically just walking around waiting to get attacked all the time.

And, as “the chosen few” were about to learn, it would soon get much worse.

Part 2

In the Wygal valley of Eastern Afghanistan in 2007, the soldiers of Chosen Company were fighting in a nearly forgotten war.

Their mission: to prevent enemy fighters from infiltrating into Afghanistan from across the border in neighboring Pakistan, and to protect the local Afghans. Lt. Jon Brostrom and his men were based at an installation called Camp Blessing. It was big and well fortified, but the soldiers also defended other much smaller and more isolated mountain outposts – including one named Bella. Chosen Company suffered serious casualties defending the little outposts.

CHRISTOPHER MCKAIG: We were really aggressive. We had to do patrols just to keep the enemy off us basically.

In November 2007, insurgents ambushed one of their patrols. Five soldiers and a Marine were killed, and all the survivors wounded. Brostrom's platoon recovered the fallen.

Sgt. Tyler Stafford was another of Lt. Jon Brostrom's men.

TYLER STAFFORD: We just lost five guys out of the First Platoon. We knew the area's pretty hot.

Their families were starting to learn a little about what they were going through. Jason Hovator's sister remembered a phone call he made back home to Tennessee.

JESSICA DAVIS: He dropped the phone, but the phone line was still open. And I could hear the enemy attacking them. And, I just dropped down to my knees and started praying: "Oh God, please don't let this be the day." And I heard the shots stop. And I heard him and his fellow soldier just start laughing like it happened all the time.

The fighting continued almost daily for months. Jason Bogar didn't tell his mother much about it on the phone, but his videos told the story.

CARLENE CROSS: When I saw it, I knew that they were in a really horrible place.

They were nearing the end of their fifteen-month deployment when intelligence reports indicated a huge enemy force was massing.

TYLER STAFFORD: Bella was getting hit on a constant rate. Intel reports of 300 enemies getting ready to overrun Bella. So we knew it was game on for them.

RICHARD ENGEL: After literally hundreds of firefights, Chosen Company became increasingly battle-hardened. And they also became increasingly suspicious of their Afghan counterparts, believing -- with their lives on the line at the end of the day – that they could only truly rely on themselves. As their deployment wound down, there was a growing unease about their mission, and it wasn't just among the enlisted men.

In May 2008, Lt. Jon Brostrom got leave and a flight home to Hawaii. It was a surprise visit.

MARY JO BROSTROM: I went to the door, it was Jonathan and he said, "Happy Mother's Day, Mom."

RICHARD ENGEL: You started –

MARY JO BROSTROM: Just – yeah –

RICHARD ENGEL: – crying immediately?

MARY JO BROSTROM: Yes, yes. Absolutely. Couldn't get that door open fast enough to get him inside the house, you know? We started talking, and then immediately he went to the laptop to show us pictures of the platoon.

These are the pictures Jon Brostrom showed his mom. But his father saw these tapes.

RICHARD ENGEL: You didn't like everything that you saw ?

DAVE BROSTROM: No. He showed me some combat footage that he took, and it was pretty shocking.

RICHARD ENGEL: What did surprise you?

DAVE BROSTROM: Some of these firefights were pretty intense. That combat outpost was being engaged almost on a daily basis. And there was not much they can do. They were sitting ducks. And I said, "What are ya doin' out there? Do you really engage with the locals? Are you providing any sort of medical assistance to them? Do you help build schools?” And he goes, "We used to. But we don't do that anymore. We just try to kill them before they kill us,” is what he told me.

RICHARD ENGEL: And that disturbed you?

DAVE BROSTROM: Absolutely.

The lieutenant's dad only grew more concerned when his son played him videos of air strikes and nighttime artillery raids.

DAVE BROSTROM: I said, "You need to get out of there." And he says, "We are. We're gonna move to a different location." And he told me, he said, "Dad, they're gonna follow us."

RICHARD ENGEL: The enemy?

DAVE BROSTROM: “The rumor is they're gonna attack us with over 300 fighters.” And I said, "Son, don't worry about it. It's the United States Army. You're gonna have plenty of power. Fire power to back ya up and to protect ya."

Despite what he had seen in Jonathan's combat videos, the veteran officer still trusted the Army to protect his son. Dave saw Jonathan off at the Honolulu airport.

DAVE BROSTROM: I told him the same thing that Mary Jo told him: I love him, and take care of his soldiers – and he'll be okay.

Back in Afghanistan, Army commanders decided to close the increasingly perilous combat post at Bella and build a new base in a village called Wanat. Wanat was a local government center, closer to their main base, and it could be resupplied by road. But the planned move was wildly unpopular with Lt. Jon Brostrom's men – who were by now just weeks from going home.

BRIAN HISSONG: We'd been up there several times. It was a terrible spot. Everyone knew it was a terrible spot to put a base.

Some of the soldiers were so worried about the move, they confided in family members. Gunnar Zwilling, Chosen Company's “little brother,” called his father, who was at a Fourth of July barbeque.

KURT ZWILLING: His words were: "It's a suicide mission. They're waiting on us. We know they're waiting on us." And he said, "Dad, it’s gonna be a blood bath."

RICHARD ENGEL: What was the tone of his voice?

KURT ZWILLING: "Dad, I don't wanna go, but I will go, because that's my job."

Pruitt Rainey, the card player, was so despairing of the move, he even told his dad to go ahead and play in a poker tournament they'd planned to do together if he didn't make it home.

FRANKIE GAY: I ask him why he was scared. I say, "You're not scared of anything." He said, "You don't understand." He said, "This is not a good place."

Jason Hovator, the devoutly Christian platoon clown, called his sister.

JESSICA DAVIS: He felt like they were going to be sitting ducks, and that an attack was imminent. And, he said, "It's not gonna be good. It's not gonna be good. Just pray that I don't go out on this mission."

Their prayers went unanswered. Two weeks before the deployment was suppose to end, Lt. Jon Brostrom got orders to move his platoon to Wanat. It would be their last hurdle before going home.

BRIAN HISSONG: Everyone was pissed off. No one wants to go to this place, especially with no time left. The general thought it was – something bad was gonna happen. None of us really knew that it was gonna be as bad as it actually was.

Part 3

In early July of 2008 – just two weeks before they were supposed to go home – Lt. Jon Brostrom and his men of Second Platoon were digging in at Wanat, their new base in Eastern Afghanistan.

SOLDIER: All we have left is to clear out this little bit of dirt.

Over the next three days the men felt exposed as they built the new outpost's defenses. The outpost was divided in sections: a football-field-sized camp where the soldiers set up their Humvees, a command post, and heavy weapons and mortars. There were about 40 American troops and 10 Afghan soldiers on this main part of Wanat.

The outpost’s other section was about 100 yards away. It was just an observation post, manned by only nine soldiers. The men called this smaller part of Wanat topside. Topside was surrounded by a single strand of barbed wire.

JASON HOVATER: This is the most sucky thing ever to do.

SOLDIER: Roger.

Jason Hovater sarcastically described their situation:

SOLDIER: Why do we have to build a big-ass hole?

JASON HOVATOR: Well, see these people up here, they want to shoot us.

SOLDIER: They all look innocent and nice, but they are not.

Chosen Company was warned by village elders that the Taliban were in the area.

TYLER STAFFORD: There's no women, there's no children in the village. Just fighting-age males.

Four days into the mission to set up Wanat, at four o'clock in the morning, Lt. Brostrom's men were already on full alert. And, in the predawn twilight, the attack came.

BRIAN HISSONG: We just started gettin' an unbelievable amount of fire.

At least 200 insurgent fighters were attacking the outpost. From one of the hills, the Taliban … first fired on the main part of Wanat, disabling the big guns and mortars. Then, the insurgents focused on the little observation post, called topside.

Sgt. Christopher McKaig was there.

CHRIS MCKAIG: They were shooting indirect at us, RPGs, small arms, and then they were down low too, assaulting us from multiple different directions.

The militants’ goal was to overrun topside and kill or capture the nine soldiers inside.

CHRIS MCKAIG: Oh, man, the whole world was exploding around you.

Sgt. Tyler Stafford was firing his machine gun with Gunnar Zwilling just beside him.

TYLER STAFFORD: And right then another explosion happened right behind us. That was the last time I ever saw Zwilling.

Another RPG slammed into their position.

TYLER STAFFORD: This is real bad. And I'm wounded in the stomach. So I'm thinking it's pretty much over for me.

The sergeant could see Jason Bogar firing away just above him.

TYLER STAFFORD: Halfway through Bogar firing – he looked down at me and saw my arm was bleeding pretty good, wrapped my arm in a tourniquet, and then went back to firing.

JEFFREY SCANTLIN: You couldn't move. People who did move are getting hit.

The soldiers at Topside were losing and dying. But a brave charge to reinforce them was about to come.

Sgt. Jeffrey Scantlin was in the thick of the fighting:

JEFFREY SCANTLIN: Lt. Brostrum had grabbed Hovater and said, "Hey, I'm taking guys to reinforce the OP."

Jon Brostrom and Jason Hovator abandoned cover. It was a 100-yard dash through blistering fire to relieve topside.

BRIAN HISSONG: Lieutenant Brostrom was at just an absolute full sprint. And Corporal Hovater was right on his heels – I could see rounds hittin’ the walls and rounds hittin' the ground. And they were runnin' right through the middle of it.

By the time they reach Topside, it was even more dire than they expected. Enemy fighters could now be seen inside the wire. The insurgents were right on top of them.

TyLER STAFFORD: I'm watching Bogar keep spraying, and then I hear Rainey shout, "He's right behind the rock, he's right behind the f***ing sandbag."

It took two more relief charges after Brostrom's and Hovator's to secure Topside, and, all the while, the soldiers below on the main base were being raked by Taliban rocket-propelled grenades and automatic weapons fire.

Finally, an hour in, the battle started to turn in the Americans’ favor, when Apache attack helicopters arrived overhead.

"... Chosen Six. Be advised we are in a in a bad situation."

This was the scene through their infrared sights:

PILOT: I'm coming in with rockets right down here.

PILOT: Firing…

BRIAN HISSONG: They were firing within, like, fifteen yards of the OP with their 30-millimeter, which is unheard of – I mean, absolutely amazing.

PILOT & GUNNER:

-All right, I have a target.

-Clear to fire?

-Where are they at?

-They're all laying down on this little ridge.

-Are you on them?

-Roger.

-Hit 'em.

Desperately needed medevac helicopters came in to a makeshift landing zone under intensive enemy fire.

BRIAN HISSONG: The position they were in, they were completely exposed to be shot at from all directions. And they just started waving to bring in casualties.

Another Chosen Company platoon reached Wanat by Humvee.

Amazingly, despite the reinforcements and air support, the battle lasted three more hours.

RICHARD ENGEL: Even with the survivors' accounts, and the gun camera and Taliban videotapes, it is almost impossible to convey the valor of the men pinned down at Wanat that day. It was simply – as a military historian put it – hell in a very small place

CHOPPER PILOT: We will have additional fallen-hero missions follow. I have a total of nine. Nine K.I.A. over.

CHOPPER PILOT: Goddammit.

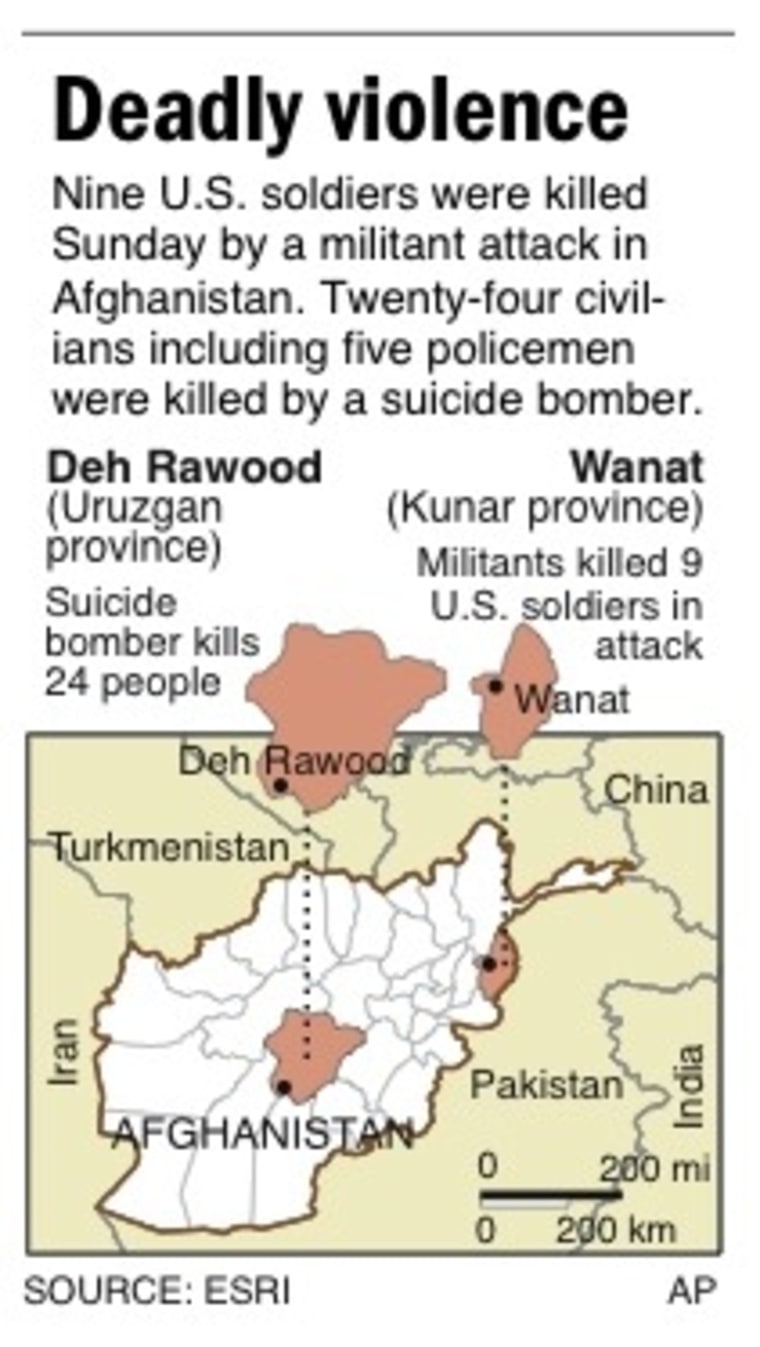

After the smoke cleared from the battlefield, the terrible toll was evident: 27 soldiers were wounded and nine of “the chosen few” lay dead. It was one of the worst casualty counts of the Afghanistan war.

Even as the wounded were being medevaced to hospitals in Germany and the U.S. for treatment, the solemn task of notifying the next of kin of those killed at Wanat was already underway.

Part 4

The Battle of Wanat was one of the worst losses of American life in Afghanistan, and, on the morning of July 13, 2008, the pain of that war reached nine American hometowns.

Jason Bogar's mother was starting her Seattle Sunday.

CARLENE CROSS: I heard a knock at the door, and I saw the military uniforms and said, "You know, just tell me. He isn't not dead?" They just looked at me. You know, from that point on, it's just like, you know, your worst nightmare.

Jason Bogar, the aspiring photographer, had been killed just two weeks before he was supposed to come home.

In a St. Louis suburb, Gunner Zwilling's dad was checking his email.

KURT ZWILLING: Front page on there was there was an attack in Eastern Afghanistan, and there was a number of dead. And I knew, just knew that – as a matter of fact, I cleaned up, waited on the front porch.

RICHARD ENGEL: You were waiting outside for the Army to arrive to notify you.

KURT ZWILLING: It was maybe 45 minutes between the time I saw the article on the internet, and the car pulled up in front of the house.

Twenty-year-old Gunnar Zwilling, Second Platoon's little brother, was the youngest soldier to die at Wanat.

RICHARD ENGEL: Here in Hawaii, one military family had just returned from church to their home overlooking Pearl Harbor. They were getting ready to go to the beach when they noticed an Army van pull up outside their door.

DAVE BROSTROM: We had a major and a chaplain standing there at the door in their – in their dress greens. And I knew immediately that something real bad happened. And then they told me that our son had been killed by small arms fire in Afghanistan.

Lt. Jon Brostom, the military brat who'd grown up to be an officer just like his dad, was dead.

And killed beside him in that first heroic charge to save their friends at the Wanat obserbation post was Jason Hovator.

Mary Jo Brostrom is a soldier's daughter, wife, and mother. Her surviving son, Blake, Jon's younger brother, is also an Army officer, but nothing had prepared her for this.

MARY JO BROSTROM: I saw my father go to Vietnam twice. David, Desert Storm. Your son takes off – but he's coming home.

The Brostrom's family friend – the colonel who commanded Jonathan's unit – called to offer his condolences. As a veteran officer, Dave Brostrom knew this day could come, but the grieving father couldn't understand quite how it happened.

DAVE BROSTROM: With the background that I had in the military, having this heavily reinforced platoon taking that much casualties – to me, it didn't make sense.

The Brostroms were extended a courtesy offered only to veteran officers: A formal PowerPoint briefing on the battle. It was conducted by their old friend, the colonel. Brostrom was troubled when his friend couldn't answer many of his questions about what went wrong at Wanat.

DAVE BROSTROM: For the majority of the questions, he told me he would get back with me. Some of the questions, he couldn't answer because of security reasons.

RICHARD ENGEL: You thought he wasn't being straight with you?

DAVE BROSTROM: Right.

Along with that briefing, Brostrom got a copy of a detailed Army investigation. It included eyewitness accounts from the Chosen Company soldiers who survived the battle.

DAVE BROSTROM: You had to read the fine print. You had to go into each soldier's testimony, which I did, and there were some things that came out that really concerned me.

One thing that jumped off the pages of the report was the location of the base.

CHRIS MCKAIG: It was like a bowl, and the top edge of the bowl would be the mountains. They had all the high ground.

JASON HOVATER: They are going to go up in those things up there called mountains and shoot weapons at us, rocket-propelled grenades at us.

DAVE BROSTROM: Nothing made sense here. Even if you look at the terrain, they were trying to establish a combat outpost in a natural kill zone.

RICHARD ENGEL: Right at the bottom of the hill?

DAVE BROSTROM: Yeah.

Brostrom learned that, as Second Platoon was digging in at Wanat, the Afghan contractor who was supposed to deliver 16,000 pounds of construction material to build defenses never showed up.

TYLER STAFFORD: We ran out of all supplies. We ran out of sandbags, Concertina wire. Had no wood.

Without heavy equipment, Jon Brostrom's men were forced to build their defenses by hand.

And, Brostrom was told, it got worse:

SOLDIER: I just want everybody to know how ******* hot it is here right now.

Brostrom discovered that his son's men were not only short of construction material, but also nearly ran out of water in the 100 degree Afghan summer.

TYLER STAFFORD: Pretty much went down to a bottle a guy – what was left.

And, Brostrom was told that on the eve of the battle, the sole predator surveillance drone that had watched over the Americans was diverted to another location. This left his son's platoon blind to the massing enemy forces.

DAVE BROSTROM: When you start peeling back the onion here, it – it gets – it gets pretty serious. All of these bad things were being reported up to the chain of command.

In the spring of 2009, a draft copy of a detailed Army analysis of the battle was leaked to Brostrom. The 240-page report was highly critical of the senior officers overseeing the operation. It confirmed much of what brostrom had learned:

- The base was in a dangerous location

- The platoon had inadequate construction material

- There was insufficient water

- Warnings of an imminent attack were ignored

- Their aerial surveillance was pulled

DAVE BROSTROM: There was nothing wrong with the mission that was given to my son. It was the resources he was given to accomplish the mission and the leadership oversight. They were nonexistent.

RICHARD ENGEL: There was a leadership failure, in your opinion?

DAVE BROSTROM: Absolutely.

Drawing on his military knowledge, Brostrom began to wage a one-man war for accountability.

GREG JAFFE: Here's a guy who spent 30 years in the – in the Army, who really loved it as an institution.

Gregg Jaffe is the co-author of "The Fourth Star," about the Army's highest ranking officers, and a reporter for The Washington Post. He covered Dave Brostom's mission.

GREG JAFFE: As he started to dig into what happened at Wanat, I think he felt like this institution he loved had betrayed him.

Brostrom spoke with anyone in the Army who would return his calls about the events leading up to the battle. Brostrom's crusade continued for months. In the summer of 2009 – a year after the Battle at Wanat – he filed a complaint with the Defense Department. He alleged negligence on the part of senior officers overseeing the move to Wanat.

DAVID BROSTROM: You can say it was arrogance. You can call it complacency. You can call it negligence or dereliction of duty. It doesn't matter.

Frustrated by the lack of answers from the Army, Brostrom went public with his campaign.

GREG JAFFEE: He continued to pound away, you know, with the media, with the Hill, and got a whole lot more “no’s,” or “We're not really interested” or “We're sorry for your loss” before he finally got some traction.

And some of the soldiers who survived Wanat were asking hard questions themselves.

JEFFREY SCANTLIN: So, what did we really accomplish there? What did those guys die there for?

Part 5

In the fall of 2009, a little more than a year after his son and eight other soldiers were killed in action in Afghanistan, Retired Army Colonel Dave Brostrom finally made some headway in his battle to learn why they died.

Brostrom got a meeting with Senator James Webb of Virginia, a former Secretary of the Navy and Marine combat veteran, who sits on the Senate Armed Services committee.

DAVE BROSTROM: I tried to summarize my argument as succinctly as possible. The more questions he asked, the more upset he became. And at the end of about an hour, he stood up and said, "I'm gonna do something."

The Senator requested that the military conduct an independent examination of the Battle at Wanat. It was Brostrom's first victory in his relentless campaign.

DAVE BROSTROM: To tell you the truth, I wouldn't have gotten anywhere if it wasn't for Senator Webb.

RICHARD ENGEL: He took it to the next level?

DAVE BROSTROM: Absolutely.

On his way home to Hawaii after meeting with the Senator,

Brostrom stopped in the Pacific Northwest and enlisted Jason Bogar's parents, who continued to struggle with the loss of their photographer-soldier son.

CARLENE CROSS: Brostrom came to Seattle and talked to us about writing senators and so on.

RICHARD ENGEL: You're glad that he's taking on this – this role?

CARLENE CROSS: Yeah.

MICHAEL BOGAR: By then, Brostrom had really done the work and had the background to do the work. So it was more just keeping up with what he found.

Brostrom also reached out to Gunnar Zwilling's father in Missouri. Zwilling couldn't forget his son's fear-filled Fourth of July phone call. He had learned early on about the problems at Wanat – getting the details from the soldier who escorted his son's body home.

KURT WILLING: I was appalled. I was mad. I had found out that they had no water. Mistake after mistake after mistake.

Zwilling was frustrated. Independently of Brostrom, he had been trying to get questions answered through his Congressional delegation – to no avail.

Pruitt Rainey's dad, who had also learned of the problems at Wanat from his son's friends in Chosen Company, read about Brostrom's crusade and picked up the phone.

FRANKIE GAY: I called Mr. Brostrom and started putting our heads together and going, "You know, this just does – don’t seem right. Something was not planned correctly.

The retired colonel, who had once commanded thousands of troops, now found himself leading a volunteer parents’ platoon, trying to learn who was responsible for their sons' deaths.

RICHARD ENGEL: Some in the military say that you are trying to second-guess something when you weren't there, trying to recreate events with the benefit of hindsight.

DAVE BROSTROM: Sure, that's a handicap. But you have nine soldiers dead, 27 wounded. It's just not a normal day in Afghanistan. So I think I'm justified to ask these questions.

Some of the families take comfort in the hope their children's sacrifice might help save other soldiers.

FRANKIE GAY: We have to learn from our mistakes. And if we as parents have to hold commanders and leaders responsible, and hold their feet to the fire, if we don't, who's gonna do it?

RICHARD ENGEL: Everyone knows what can happen to soldiers who are in front line units.

CARLENE CROSS: Yes. And I understand that. This situation was pure recklessness though. You just have to say, "This is wrong, and the Army needs to look at this situation and learn from it, so they don't do this again."

RICHARD ENGEL: What are you looking for now?

DAVE BROSTROM: What I really want is the lessons to be learned so that units going to Afghanistan can read about this, and hopefully commanders will prepare so this doesn't happen again.

MARY JO BROSTROM: I don't want this to happen to any other family

Part 6

In Honolulu, just before Christmas 2009, Jonathan Brostrom's six-year-old son Jase accepted a Hawaii Medal of Honor on behalf of his father, who was killed in the Battle of Wanat.

The state honor was only one of the scores of decorations – including Silver and Bronze Stars for valor – awarded to the nine soldiers who died.

Those famililes remain profoundly wounded.

KURT ZWILLING: He was the light of my life. Until im lying in the grave next to him, I'll never get over it. It'll never be over.

Reminders of their lost loved ones were all around them.

FRANKIE GAY: He was gonna train here and become a mixed martial artist.

Pruitt Rainey never saw the home gym his dad built for him just below their poker room. But his father kept the promise he made to his son in that final phone call from Afghanistan.

FRANKIE GAY: The last thing he told me was to go ahead and play in the World Series of Poker if he didn't make it home. So, a year later, we all went to Las Vegas and the World Series of Poker main event and played for Pruitt.

ESPN ANNOUNCER AT WSOP: "They're all here in support of this man who has come to the main event this year... "

FRANKIE GAY: It was the greatest trip of my life, and it was as if he was right there. He loved being part of Chosen Company, and “the chosen few.” To him, it was a complete honor. His nickname's “The Warrior.” That's on his tombstone.

For Jason Hovator, a much different dream was denied.

JESSICA DAVIS: He would have been working at a church full time, and leading the music there. On his tombstone, it says that he was a psalmist of the Lord. He loved God, and he loved his country, and he fought for us all.

In Seattle, a mother wonders what might have been for her son, the photographer-warrior, Jason Bogar.

CARLENE CROSS: I think he would've gone to art school. He would say, "I want to be an international correspondent, and shoot for maybe, you know, the news, or National Geographic.” I think he would've been fabulous. Because if you look at his pictures, he had a way of connecting with people.

On Jason's laptop, his parents found a letter to his family:

"I pray to God no one will ever have to read this. Never have I felt so strong as I do that what I am doing here in Afghanistan is the right thing. As a result of that, death is easier to accept. I'm just sorry that you all have to suffer for it now.”

Across the Pacific, on Waikiki Beach, when the break is good but not too big, Lieutenant Jonathan Brostrom's son Jase surfs with his grandfather on the same tandem board he once shared with his dad.

Meanwhile, the families finally seemed to be getting somewhere in their campaign to hold someone accountable for their sons' deaths. Though the military investigation wasn't complete, in March the Army did issue letters of reprimand to three commanding officers for failing to properly prepare the defenses at Wanat. a letter of reprimand can effectively end an officers career.

Most of the Chosen companies soldiers who survived the battle of Wanat including those who were injured, remain on active duty. Today they're in Kunar province, less than 15 miles from Wanat, they're back in almost exactly the same place. And these mountains and their mission remain just as dangerous as ever."

We joined them for a week of patrols in early 2010 and we watched as Sgt. Christopher McKaig—one of the few to survive topside—reenlisted for another four years.

U.S. policy has changed since Wanat. The military is giving up many of its small outposts. They’re too isolated, too hard to defend and make little strategic difference.

One of the first outposts to go was Wanat. It was evacuated just a few days after the battle there.

We showed Taliban propaganda video of the attack to some of men who fought there.

JEFFREY SCANTLIN: After all that, after all the people we lost and all the people that was wounded, we pulled out.

Sgt. Jeffrey Scantlin was awarded a silver star for heroism at Wanat:

SOT JEFFREY SCANTLIN: So, what did we really accomplish there? What—what did those guys die there for?

RICHARD ENGEL: And what’s your answer to that?

JEFF SCANTLIN: They died fighting for their country, but their lives and the reason why they’re—they had to give up their lives was ultimately for nothing ‘cause we pulled out two days later.

As Chosen Company soldiers continue to fight in Afghanistan, back home the Brostroms and the other families pushed ahead with their mission for accountability. Last week they got news of a major development. The Pentagon was about to release the results of its independent investigation into the battle of Wanat.

Family members traveled to an Atlanta Army base to hear the findings on Wednesday. In a private briefing—taped by one of the parents—the Marine Corps general in charge of the investigation conceded the Army made serious mistakes.

LT GEN RICHARD NATONSKY: We felt there was a dereliction of certain elements in the chain of command as a result of their inaction prior to the battle.

But then, in a move that stunned the assembled families, a second general—

GENERAL CAMPBELL: I want you to understand the actions I took and why I took those actions.

The same Army officer who had issued those letters of reprimand to the commanders overseeing Wanat—reversed his earlier decision.

GENERAL CAMPELL: The officers listed in the report exercised due care in the performance of their duties.

The general said the officers at Wanat did the best they could with the limited resources they had. He announced was exonerating them of any negligence, and revoking the letters of reprimand.

DAVE BROSTROM: You take a look at the facts that General Natonski did, an independent investigation, you went out and did your own, and you you came up with totally a 180-degree outcome.

Dave Brostrom, the retired colonel, lead the families counter attack challenging the general as the room practically exploded:

DAVE BROSTROM: You have a platoon sitting out there exposed in enemy territory and nobody’s doing anything to mitigate the risk. What the heck was the battalion commander thinking?

GEN. CHARLES CAMPBELL: I can absolutely understand your emotion.

Dave Brostrom: You can not. You didn’t lose a son.

CARLENE CROSS: You’re accountable morally to the United States and our dead sons but you can do whatever you want and cover your butt with the Army and it’s—it’s over. And that’s what I feel like this is.

We sat down with some of the family members right after the briefing.

CARLENE CROSS: It was frightening to sit there as a parent and think, “There is no accountability here.”

KURT ZWILLING: Did the Army learn anything? Doesn’t seem like it.

JESSICA DAVIS: General Campbell, he kept sayin’ that all of the commanders’ decisions were reasonable. Nine soldiers being killed, 27 wounded and that’s reasonable? I don’t understand that

DAVE BROSTROM: This is not the Army that I grew up in. This would not have happened. And you know, I can’t explain the reasons why. I’m embarrassed. And very disappointed.

As the families struggle with feelings of betrayal and grief—soldiers from Chosen company remain on the front line in Afghanistan, just a few miles from Wanat, where their lives and those of so many others changed forever.

BRIAN HISSONG: I’ve heard people say that it was all for nothing. I don’t really believe that. The guys that fought and the guys that died, they died for the people next to ‘em. You know, they died to—to try to keep their friends alive. The bottom line is those guys fought their hearts out for each other.