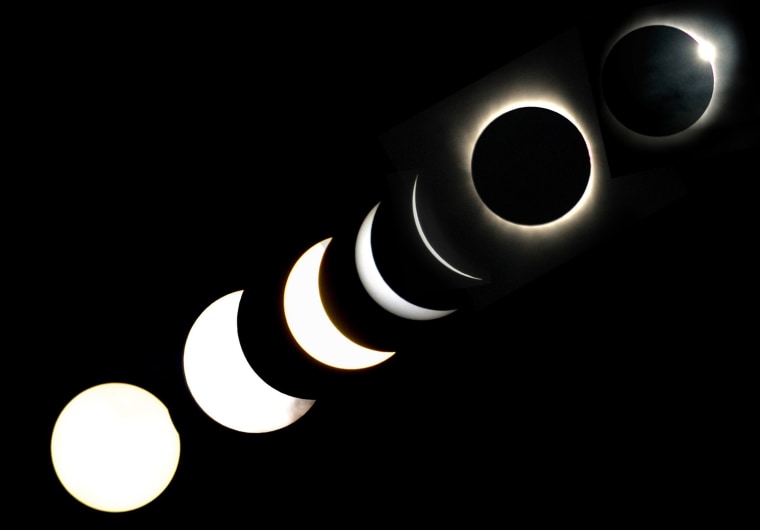

A total solar eclipse on July 11 has the potential to give some ground-based observers a stunning five-minute celestial show, but you'd almost have to go to ends of the Earth to try and see it.

Solar eclipses occur when the moon gets between the sun and Earth, blotting out some or all of the sun.

While the moon's dark cone of shadow (called the umbra) will pass more than one-third of the way around the Earth during this solar eclipse, virtually the entire ground track for the event falls over the remote open ocean waters of the South Pacific. Land encounters will be very few and generally far between.

(This graphic shows the ground track depicting where this total eclipse of 2010 will be visible from and when.)

For astronomers, total solar eclipses provide an opportunity to observe the pearly white corona, or outer atmosphere, of the sun. They occur when the moon comes between the Earth and the sun, completely obscuring the sun from our persepective.

The corona's brightness is only about one-millionth as bright as sunlight, but when the moon completely obscures the visible disk of the sun the corona shines out in magnificent splendor.

Today, we needn't wait for an eclipse to observe the corona astronomers use an instrument called the coronagraph, developed in 1930 by the French astronomer, Bernard Lyot to observe the brighter, inner part of the corona. But the beauty and awesomeness of a total eclipse are still unequaled and is why some will travel long distances, to remote parts of the earth or on the ocean to experience this glorious spectacle. (Solar Eclipse Photos)

Story of the shadow

On July 11, the moon's shadow will touch down at local sunrise about 870 miles northeast of the North Island of New Zealand and only three minutes later will sail through the Cook Islands, narrowly missing the most populated (Rarotunga), but passing over the second largest (Mangaia). Weather permitting, it should afford the 1,900 who live there a 3-minute, 18-second view of a totally eclipsed sun.

After another 10 minutes, the umbra will glide east-northeast past the Society Islands, barely missing the island of Tahiti by a mere 15 miles. If you are stationed on the south coast of Tahiti Iti, "Little Tahiti," you would see 99.3 percent of the sun's diameter blocked by the new moon.

About five minutes later, the dark lunar shadow will take a roughly 15-minute trek through French Polynesia into the Tuamotu Archipelago the largest chain of atolls in the world, spanning an area roughly the size of western Europe.

When the umbra departs the Tuamotus at around 18:48 UT, it will spend the next 83 minutes traveling 2,000 miles over the lonely waters of the South Pacific. At 19:33:31 UT, literally in the middle of nowhere, the total phase of the eclipse will reach its maximum duration: an exceptionally long 5 minutes, 20 seconds.

However, unless you're on a properly positioned boat or aircraft, this prolonged view of the sun's corona will go unseen.

Easter Island in eclipse

But 35 minutes later, the shadow fortuitously makes a direct hit on one of the world's most isolated islands: The legendary Easter Island, known for its many hundreds of monolithic statues of various sizes that were erected by its native Rapanui people.

At Hanga Roa (pop. 3,300) the main town, harbor and capital of Easter Island totality will last 4 minutes. 41 seconds, which is only 39 seconds shorter than the maximum. Here, totality will take place in the early-afternoon, with the sun 40 degrees high above the north-northwest horizon.

After departing Easter Island, the Moon's umbra will cross another 2,300 miles of open ocean before making its final landfall in Patagonia. It will reach the rockbound coast of Chile, sweeps over the Andes and into Argentina and just before sliding off the Earth's surface (at 20:50 UT), passes over the town of El Calafate, where totality will last 2 minutes, 47 seconds, but with the sun only 1 degree above the horizon.

Chasing the solar eclipse

A number of tours and expeditions have been organized to view this upcoming eclipse. As one would expect, considering the lunar shadow's considerable interaction with the South Pacific, most of these are on cruise ships.

There is an advantage of an eclipse cruise in that the ship's mobility can be factored in, allowing for last-minute maneuvers to avoid any possible unsettled weather that might otherwise obscure a view of the darkened sun. Climate data is carefully scrutinized to determine where the best possible weather might be found along the eclipse track.

The best location appears to be near Hao Island in French Polynesia, where typical cloud obscuration values register at around 45 percent.

At Easter Island, this figure increases to 55 to 60 percent, while at Mangaia it jumps to 65 to 70 percent while at El Calafate it registers almost 80 percent.

As discouraging as some of the figures are, however, keep in mind that in the past there have been cases where places with excellent weather prospects ended up with clouds while places with poor prospects ended up seeing the eclipse. As science fiction writer, Robert Heinlein (1907-1988) once noted: "Climate is what you expect, but weather is what you get!"

Solar eclipse addict

The only guaranteed view of totality would be from a jet aircraft.

One in particular, a Skytraders Airbus A319LR/ACJ, will not only rendezvous with the moon's shadow, but will actually race it thereby prolonging the duration of totality for approximately 9 and a half minutes while flying at an altitude of 40,000 feet.

The person who has mapped out the circumstances for this unusual flight is Dr. Glenn Schneider, an astronomer at Arizona's Steward Observatory, and the Project Instrument Scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope's Near Infra-red Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer. He is also an umbraphile; literally a "shadow lover", but properly applied, one who is hopelessly addicted to the glory and majesty of total solar eclipses.

"Those who have basked in the moon's shadow will know what I mean without further explanation," Schneider writes. "Those who have not may have difficulty in understanding that umbraphillia is not only an addiction, but an affliction, and a way of life."

Schneider is indeed addicted to eclipses.

He saw his first in 1970. July 11 will be his 29th total solar eclipse. He has spent nearly 82 minutes "basking" in the shadow of the moon. If you're interested in joining him on what he has billed as "EFlight 2010," you can contact him directly at: gschneider@as.arizona.edu

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.