IT used to be that when a glacier had a bad night it was like that proverbial tree falling in the forest.

Now ice researchers using several satellites to monitor Greenland's most active glaciers almost daily have caught the north limb of the mother-of-all-Greenland glaciers, Jakonbshavn, retreating a mile in a night.

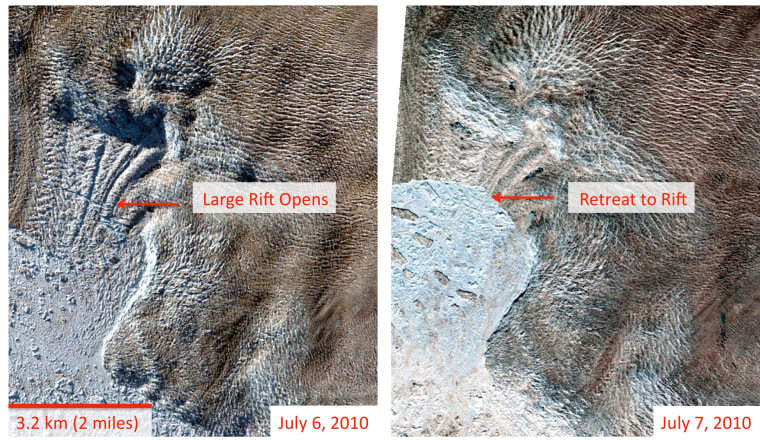

"A few nights ago a crack opened up," said Tom Wagner, cryospheric program scientist at NASA. "Two nights later (July 6) the whole thing breaks off and flows away." The lost portion has been described as about an eighth the size of Manhattan Island and set a new record for the retreat of that glacier.

But that's not all. On July 12 there was a new large crack discovered in the glacier's southern limb as well. Whether that means another gigantic release of ice or not remains to be seen.

Jakonbshavn is already well known for being a major exit route for 10 percent of the ice that leaves Greenland for the sea. The river of ice fills a vast valley which, if emptied, would rival the Grand Canyon in scale.

It appears that the record retreat of Jakonbshavn may have been helped by an exceptionally warm winter, which prevented sea ice from forming in front of the glacier, said Ian Joughin of the Polar Science Center Applied Physics Lab at the University of Washington.

There's usually about four miles of sea ice floating in front of the glacier, keeping the water nice and chilly near the calving front of the glacier -- and less prone to calving off icebergs.

Normally the glacier retreats in the summer, then regains ground in winter as it surges towards the sea with the help of sea ice. The lack of sea ice appears to have changed that, say researchers.

"This year it started (calving) where it left off last summer," said Ian Howat of the Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State University.

In the past, satellite images could be months or years apart. Over such periods glaciers can advance and retreat many times, making the few snapshots only useful for determining long-term trends. For a more detailed study of just how glaciers behave, a better time-resolution was needed.

"It's exciting because there's a lot we don't understand," said Joughin. Getting higher time-resolution images like those that caught Jakonbshavn retreating so quickly finally lets researchers begin to study the basic principles of glacier behavior.

The satellites the researchers are using to keep almost daily tabs on the giant Jakonbshavn, Kangerlugssuaq, and Helheim glaciers, and weekly checks on smaller outlet glaciers include DigitalGlobe's WorldView 2, which takes optical (visible light) images.

When clouds get in the way, radar images can be used from a German satellite that can penetrate the cloud cover. Data is also being used from Landsat, Terra, and Aqua satellites.