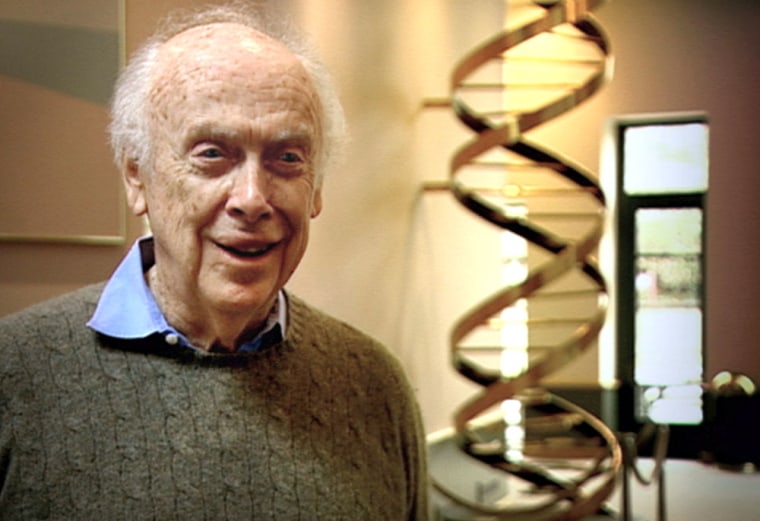

James Watson, who rocked the human race a half-century ago by discovering the DNA molecule’s double-helix structure, has only one complaint about “DNA,” a documentary series in which he serves as the overarching presence.

“I wish they had shot it 20 years ago when I didn’t look so old,” the 75-year-old Watson says with a rueful laugh. “It’s not the view I have of myself.”

Still, a big part of his view of himself — also clearly visible to the outside world — is that of someone who likes to rock the boat and create waves. And that part seems impervious to age.

“I haven’t changed my behavior since the age of 10,” he says in his Manhattan apartment high above the East River. “It’s not because I became famous.”

Watson upholds practical solutions and the bold pursuit of them, and, along the way, he says what he thinks. (”If we don’t play God,” he declares on “DNA” in its first moments, “who will?”)

Thrilling story retold

But there is more than Watson’s outspokennness on this epic series of five weekly programs, which begins Sunday on most PBS stations (check local listings). Each is a freestanding, digestible hour that hears from other key figures while using you-are-there visuals and computer animation to investigate a story that, after 50 breakthrough years, is more thrilling than ever.

“We’re in the midst of a revolution,” says Watson, wearing the slightly bemused smile with which he greets the world. “It will affect the way we think about ourselves every bit as profoundly as the one which occurred after Darwin’s ‘Origin of Species,’ which shocked a lot of people. We’re related to monkeys! That was a really upsetting thought and, for some people, still is.”

On “The Secret of Life” this Sunday, Watson retraces the contest he and Francis Crick waged against a rival team of young scientists, Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, as well as a third contender, Nobel laureate Linus Pauling.

With the discovery by Watson and Crick that the DNA molecule forms a double helix — resembling a ladder twisted into a spiral — the manner in which DNA could carry a living thing’s genetic code and precisely duplicate it became clear. Their findings were published in April 1953 and won them the 1962 Nobel Prize in medicine and physiology, which they shared with Wilkins. (Franklin, who had died from cancer in 1958, was a vital but largely overlooked participant, and the subject of “Secret of Photo 51,” a PBS documentary that aired last April.)

After that discovery, says narrator Jeff Goldblum (who himself played Watson in a 1987 TV docudrama), “whole new fields of science and technology burst into being, as our understanding of the genetic code buried in DNA grew.”

The subsequent “DNA” episodes:

- “Playing God” (Jan. 11) introduces the pioneers who carried out the first genetic engineering experiments, which triggered an outcry over the dangers of genetic manipulation while spurring a multibillion-dollar biotech industry whose early products included genetically engineered insulin and genetically improved cotton and potatoes.

- “Human Race” (Jan. 18) chronicles another bruising competition. This time, two groups of scientists scrambled to be the first to catalogue all 38,000 genes in the human genome, which could serve as an “instruction manual” for troubleshooting diseases and disabilities in humans. After a decade of epic labor and bitter rivalry, success by all was declared at a celebration thrown by President Clinton at the White House in June 2000.

- “Curing Cancer” (Jan. 25) notes that all cancers are caused by damage to DNA. And when a faulty, cancer-causing gene is identified and the right drug is developed to repair it, then that particular cancer can be cured. Example: Bud Romine, who, near death in 1997 from chronic myeloid leukemia, became the first patient ever to take a drug called Gleevec. Within 17 days, he was healthy. More such drugs for other cancers are on the horizon.

- “Pandora’s Box” (Feb. 1) returns the spotlight to Watson, who contemplates the future of genetic science. He speaks of a “new eugenics” that might address what he calls genetic injustices (such as Down Syndrome, cystic fibrosis or mental illness), giving people the means to correct them. And what’s wrong with people customizing the evolution of their descendants to assure a better-looking or smarter kid?

These are exciting but often thorny issues, and Watson embraces them — both as a public advocate and as president of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, one of the world’s leading genetic labs.

“I’m just trying to use common sense,” he says, punctuating his point with a grin and chuckle. “There are still big things you could do and that I’m trying to do. Cancer hasn’t been stopped yet. And I’m still trying to be a better tennis player than I was when I was 25.

“My dream would be to die playing singles tennis,” he confides. “Not doubles! Doubles is an old man’s game.”