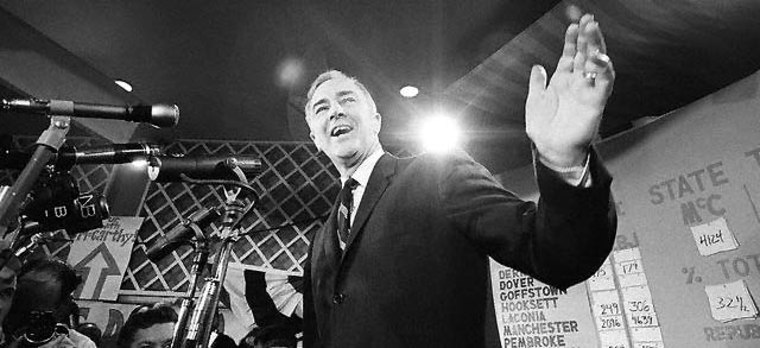

In 1968, Minnesota Sen. Eugene McCarthy "won" the New Hampshire primary with 42 percent of the vote, even though he finished second to President Johnson who got 50 percent.

Reporters and pundits proclaimed McCarthy the winner because he had exceeded expectations by doing so well against an incumbent president.

Two weeks after McCarthy’s strong showing in New Hampshire, Johnson announced that he would not run for re-election.

The New Hampshire primary does not usually produce such historic results, but that doesn’t stop reporters from looking for pulse-pounding comebacks and upsets.

The expectations game

In the often quirky history of the two first contests, the New Hampshire primary and the Iowa caucuses, which precede the primary by one week, what counts are the expectations going into the voting, expectations partly “spun” by the candidates themselves.

The news media and campaign strategists create story lines to interpret the results of the two contests, sometimes in ways that lay camouflaging smoke over the factors that determine the nominee.

The candidacy of Arizona Sen. John McCain in 2000 provides one case in point. McCain’s New Hampshire victory over George W. Bush got very big and mostly positive play in the media, but reporters sometimes failed to note the big crossover vote working for him there. Independents could vote in the Republican primary; many voted for McCain. His win a few weeks later in Michigan was due partly to Democrats who voted in the Republican primary.

Then McCain, who had been running a cheerful “Happy Warrior” campaign, turned acerbic, calling Republican religious conservatives such as Pat Robertson “the forces of evil” and comparing Robertson to Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam.

Once McCain got to a Republican primary which was open only to Republican voters, California’s on March 7, this rhetoric did not play well, and Bush beat by him by a 2-1 ratio.

Clinton's New Hampshire success

But sometimes a better-than-expected finish in Iowa or New Hampshire is a harbinger of a candidate’s resilience.

In 1992, Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, damaged by revelations of draft dodging and extramarital philandering, beat expectations by winning 24 percent of the vote in New Hampshire.

Former Massachusetts Sen. Paul Tsongas finished first in a crowded field with 33 percent, but Tsongas was a next-door neighbor to New Hampshire, so reporters discounted his victory.

That same year the news media made much of Patrick Buchanan's 37 percent showing in New Hampshire’s Republican primary -- even though President George Bush won it with 53 percent.

Buchanan, now an MSNBC commentator, was a witty and quotable candidate while Bush seemed to be an out-of-touch incumbent.

But Buchanan’s showing was not to be another McCarthy-vs.-LBJ saga. Bush stayed in the race; Buchanan returned to punditry and four years later he mounted another maverick run, this time against Bob Dole.

Buchanan’s significance in 1992 and 1996 was not that he had any chance of wresting the nomination from the Establishment candidates (Bush and Dole) but that he epitomized conservative discontent with the Republican nominee. In 1992, that discontent probably cost Bush the election.

A “better-than-expected” performance or even an outright win in Iowa or New Hampshire sometimes can not compensate for lack of money, for tactical blunders, or for the case in which party activists have simply "fallen in love" with a more alluring candidate.

Bush's 'Big Mo' evaporates

In 1980, for instance, the first George Bush bragged that he had “Big Mo” — momentum — after he won the Iowa caucuses.

But in most states, the hearts of the Republican faithful were with Ronald Reagan. In the New Hampshire primary, Reagan crushed Bush and strolled on to the nomination.

In 1984, the news media deemed Colorado Sen. Gary Hart a big winner in Iowa because he got 16.5 percent to former Vice President Walter Mondale's 49 percent. Another way of looking at the results is that Mondale beat Hart by nearly a 3-1 ratio. In most elections that would be a spirit-crushing defeat for Hart — but this was Iowa and the rules are peculiar there.

Some Democrats and some in the news media wanted an alternative to the gray and familiar Mondale. On the strength of glowing media coverage, including a cover story in Newsweek, Hart won the New Hampshire primary, beating Mondale by nine points.

But Hart's team later blundered in the run-up to the Illinois primary by running a negative ad linking Mondale to Chicago machine politician Eddie Vrydolak.

Hart ordered the ad pulled it off the air, but his operatives were unable to do so.

"Senator, if you can't run your own campaign, how can you run this country?" Mondale taunted Hart in a debate.

“The Mondale campaign had been trying to paint Hart as an unsteady leader, and we had played into their hands,” Raymond Strother, Hart’s advertising consultant, ruefully wrote later.

Hart lost the Illinois primary and his campaign sputtered to an end.

This year, with a slew of primaries in January and February, an insurgent such as Hart was in 1984 might not even make it to Illinois, which holds its primary on March 16.

Money makes the nominee

As in years past, any contender who surpasses expectations and captures the fancy of the news media based on the Iowa and New Hampshire results will have his moment of glory. But the ability to sustain a campaign over several weeks and in several states at once will likely determine the nominee.

In every contest since 1980 — with only one exception — the candidate who has raised the most money in the year before the primaries ended up winning the nomination. That sole exception was Republican John Connolly in 1980 who lost to Reagan.

In 2003, the Democrat who raised the most money was Howard Dean, more than $40 million. His money puts in him in the strongest position to compete not only in Iowa and New Hampshire but in the 19 primaries and caucuses that take place next month.