Sending a child to college takes more than good grades and a big check these days. More than ever, it requires compromising on where to attend or taking on a mountain of debt — or both.

Two-plus years of economic malaise have made four years of college that much harder to pay for. This has prompted many families to delay or alter their plans.

It's not just that tuition and fees are still rising 5 percent or more a year. Grants and financial aid awards, too, have failed to keep pace. The resulting price tags are as high as $55,000 a year at elite colleges and $28,000 for some students to attend their state universities.

College-bound students clearly are factoring cost more heavily into their school choices, sometimes after having tough conversations with their parents. They are shifting from private to public colleges, taking "gap years" after high school to save money or attending school part-time while working, based on enrollment figures and anecdotal evidence from admissions counselors and other experts.

To cover the extra costs, parents are increasingly dipping into retirement savings and loading up on debt.

So are their children. Student loan debt surpassed total credit card debt in this country for the first time this summer, totaling $850 billion, according to financial aid expert Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of FinAid.org. As one troubling consequence, the national student loan default rate has risen in each of the last three years.

While enrollment numbers are up nationwide, the strain for families to complete their education is evident. Applications for financial aid are soaring, and families at all income levels are appealing for more assistance. More students are enrolling in two-year colleges and asking private admissions consultants for more cost-saving options to consider.

"Parents are calling about their lower income and lost jobs. They're really scared," says Katherine Cohen, a college admissions counselor and founder of ApplyWise, an online college admissions counseling site. "I see much more urgency than before the financial crisis."

Choosing a school

It may require some creative planning, but many families are finding ways to navigate the cost maze without jeopardizing their financial future.

One increasingly popular option is going to community college for a year or two before finishing at a four-year school. Enrollment at the nation's nearly 1,200 community colleges has jumped 17 percent in the past two school years, nearly double the increase at universities or private colleges. It's a strategy that can cut the cost of a bachelor's degree nearly in half.

The approach, while not their first preference, is working for families like the Altons of Rockville, Md.

The recession confirmed for Lucy Alton, an English teacher, and her husband, Rolando, a biochemist, that they would have to send their daughter to a nearby community college, Montgomery, this fall. With no pensions, a late start on retirement savings and a combined income of less than $100,000, and with the couple already supporting Rolando's mother, community college made financial sense.

"It has been a bit of a struggle to come to terms with community college as the only option, because I had been able to attend a very fine liberal arts college in my day," says Lucy Alton, 51, who went to Bryn Mawr College. "There's a cultural expectation that your child will go to a college with a name on the sweatshirt that will stop traffic. But this is much better for us and it's much better for her."

Their daughter, a technical theater major, is content with the decision, her mom says. Instead of paying tens of thousands of dollars a year at a name-brand school, she is attending Montgomery for free thanks to a merit scholarship that covers the $4,272 in annual tuition and fees. After she gets her associate's degree in two years, she plans to pursue her B.A. elsewhere — debt-free.

"I just don't want student debt to control our daughter's life choices the way my debt controlled some of mine," Alton says.

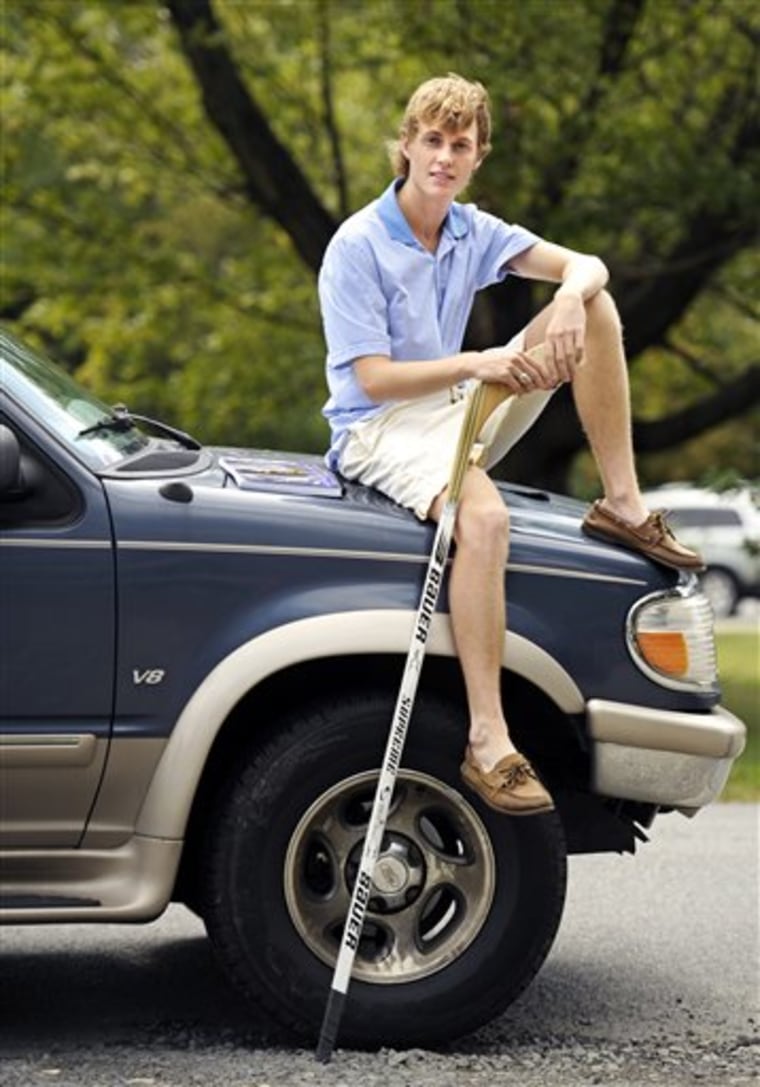

Griffin Boyle, 18, of McLean, Va., was accepted at Penn State University, which he wanted to attend for its sports journalism program. But tuition, fees and room and board would have cost more than $36,000 a year. So he is living at home and commuting to George Mason University, a state school that costs $8,700 in tuition and fees.

"It isn't any longer about me sitting upstairs while my parents are sitting downstairs crunching the numbers. It's become a discussion about what the three of us can do," Boyle says. "I thought of this as an opportunity to take advantage of a school that's 15 minutes away, save an immense amount of money, definitely make my parents happy."

He hopes to ultimately finish his degree at a pricier school.

Paying the bill

Total grant aid has been rising slightly, including federal Pell Grants for the neediest students. But there isn't nearly enough aid to meet surging demand. A 40 percent rise in the number of applicants for federal student aid from two years ago has shrunk the average amount available to each student in need.

The widening affordability gap is limiting college access for some high school graduates, according to a report made to Congress this summer by the Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance.

"It used to be that if you came from a low- to middle-income family you could graduate from college without any debt, between state and federal grant aid," says Lauren Asher, president of the Institute for College Access and Success in Berkeley, Calif. Now, she says, with the economy causing a strain not just on families but state budgets, and funding for colleges and universities too, it's often a question of whether they can go at all.

Borrowing has become a primary, albeit costly, vehicle to a college degree. Sixty-seven percent of students graduating from four-year schools in fiscal 2008 carried student loan debt, according to government statistics. That number has increased 27 percent in four years and more than doubled since the early '90s.

Even at public universities, graduates with student loans carried an average $20,200 in debt. More excessive debt loads have become commonplace, too. About 10 percent of bachelor's degree recipients in 2008 borrowed $40,000 or more.

Those heavier burdens in a troubled economy led to a spike in the number of borrowers who defaulted on their federal student loans in 2008, the most recent year for which data are available. Figures from the U.S. Department of Education show that 7 percent of borrowers defaulted within two years of beginning repayment. The increase was seen for graduates of both private and public schools.

Suzan Bekiroglu, 24, graduated from the University of South Florida last month with a bachelor's degree in international studies and $24,000 in student loan debt. She has until February before she has to start making payments, a daunting prospect when she hasn't found a job.

She has concerns about finding a job that will allow her to comfortably manage her debt load. "Though I'm trying to stay positive, I feel like I'm in a conundrum and couldn't have graduated at a worse time," she says.

Striking a balance

Parents are stepping up to take on big loans or raiding their retirement savings after their existing college savings have run dry, even though financial planners advise them not to. Many are shocked to learn that the formula for federal financial aid counts on parents contributing large amounts — often tens of thousands of dollars a year for even families of modest income — before aid kicks in.

Paul Wrubel, a college admissions consultant in San Mateo, Calif., keeps a box of Kleenex in his office for emotional parents of high school students.

"Parents are so unhappy," he says. "In the absence of a proper support system, they either downgrade their college plans and take their inability to pay tuition as a parent failure or they invest their retirement in their child's education and they can't retire."

The risk of undermining a potentially secure retirement is why attending a public college in-state or a community college may make more sense than shelling out for a dream school.

After all, inadequate retirement savings may just lead parents to depend on their kids in later years. That prospect should serve as a cautionary tale for those who would borrow any amount to send their child to the best college they can get into.