Hackers are getting better by the day at cracking sophisticated passwords, and the major computer companies seem to be achieving little in their efforts to stop the trend. Fed up with remembering a dozen passwords, most of them probably outdated, Thea DeSilva took matters into her own hands and constructed a mobile password device that has simplified and enhanced her personal online security situation.

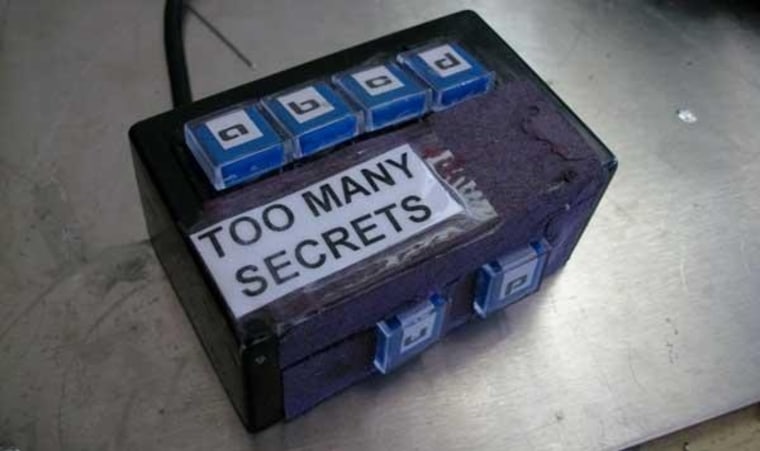

The device, which she created as a hobby and named the “Passy Pass,” generates nearly random passwords for every site, stores them, and protects that library of passwords behind an equally safe set of PIN codes. Similar devices already exist for consumer use, but with a little ingenuity, DeSilva’s plans (which are online) and software, adventurous techies can assemble one themselves.

“I don’t like typing passwords so much,” DeSilva, a former pharmacy technician from Minnesota, told TechNewsDaily. “I tend to pick bad ones, or reuse them, and that’s just part of human nature. They’re supposed to be random, but we’re not that good at randomness. It’s better to let the device do it.”

The Passy Pass connects to the computer through the USB port and functions as a digital key ring for the Web. When DeSilva opens a new account, she types in the general PIN for the Passy Pass, which then spits out an 11-digit password that is generated based on how long it took her to enter the personal identification number. Since no one could ever hit the keypad in the exact same number of milliseconds, the passwords keep changing.

DeSilva then assigns each password its own ATM-code-like PIN. Since the personal identification numbers don’t actually access the site, she can write them down without fear. To log onto a site, she simply inputs the PIN code into the Passy Pass, which in turn puts the password into the site.

The device is small enough for DeSilva to carry around, letting her Internet keys rattle right next to her physical ones.

The Passy Pass does have some weakness, according to Bill Cheswick, a security scientist at AT&T research. Cheswick told TechNewsDaily that another layer of protection between the device and the PIN code would really help, and he worries that keystroke logging malware could intercept the password as it moves from the device to site.

Still, Cheswick thinks DeSilva is moving in the right direction. “This kind of approach is promising,” Cheswick said.

“We ought to have keys to use our computers, just as we have keys to use our cars.”