Cities and counties can't stop U.S. immigration officials from sifting through local police records to root out illegal immigrants, even though Immigration and Customs Enforcement has characterized the program as voluntary since it started up two years ago, federal documents show.

When a local law authority arrests someone, it submits his or her fingerprints to the FBI to confirm identity and check for a previous criminal record. That's been a standard part of the booking process in every police agency in America for decades.

Under the disputed program, called Secure Communities, the FBI automatically shares those fingerprints with ICE, which checks to see whether the person is in its database for any reason. If not, ICE steps out of the picture. But if so, ICE then looks more closely to determine whether the person is "eligible for deportation" — either by being in the country illegally or by holding a green card that's been invalidated by a previous conviction.

If that's the case, ICE can begin proceedings to take the person into federal custody for possible deportation. While the Secure Communities (PDF) say ICE "normally" won't remove a "criminal alien" until the local case is resolved, they specify that the agency can begin the process to do so "at the time of booking" so it can move quickly once the case is concluded.

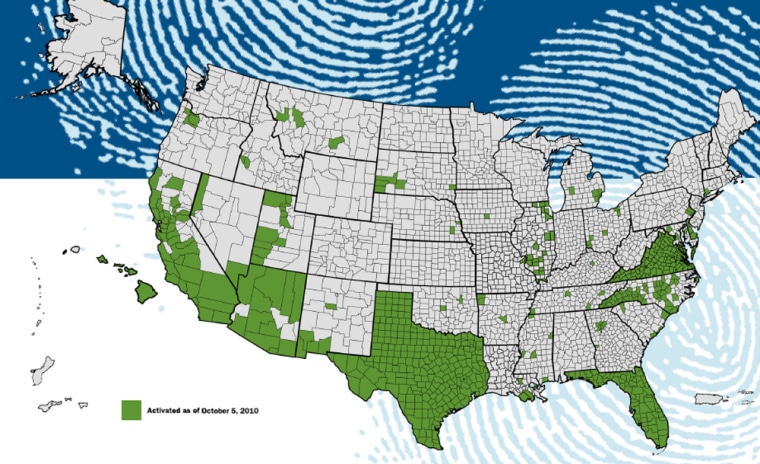

The program has been implemented in phases since it was created late in the administration of President George W. Bush, and ICE now reviews all arrests in more than 650 cities and counties in 33 states. The Obama administration, which has strongly backed the program it inherited in January 2009, said it hopes to implement Secure Communities nationwide by 2013.

Some local elected officials in nearly every state have objected to Secure Communities, news reports show, citing concerns that immigrants will stop cooperating with police as witnesses for fear of running afoul of ICE.

Some immigration activists also allege that it's being used as a dragnet to round up illegal immigrants indiscriminately. ICE vigorously disputes that, but its own statistics (PDF) reveal that 78 percent of the 56,358 people deported through the program through August, the last date for which full figures were available, hadn't been convicted of a violent crime. Twenty-six percent had no criminal convictions at all.

Concerns like those have led at least four communities — San Francisco; Washington, D.C.; Arlington County, Va.; and Santa Clara County, Calif. — to formally request to opt out of Secure Communities.

This is where things get confusing.

'Yes or no?' Since Secure Communities began rolling out in October 2008, ICE has indicated that local participation is voluntary. As recently as August, it outlined a process for local officials to object and to negotiate a resolution that "may include ... removing the jurisdiction from the deployment plan."

At the same time, ICE's internal documents make it clear that the agency has always considered Secure Communities to be a federal-only program in which local officials have no say. Just last week, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano said she didn't "view this as an opt-in/opt-out program."

So which is it? Can cities and counties opt out?

ICE officials have repeatedly refused to clarify whether local jurisdictions can prevent ICE from using their police records to identify deportable illegal aliens. Asked to explain conflicting language in ICE documents that appears to characterize Secure Communities as both mandatory and optional, spokesmen for the agency said they couldn't comment.

That frustrates local officials in jurisdictions that are seeking to opt out of the program.

"Is there an opt-out — yes or no?" asked J. Walter Tejada, a member of the Arlington County Board in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, which recently voted to opt out, only to learn it couldn't. "We have had a number of conflicting statements on the part of ICE."

Some activists in the debate over illegal immigration accuse the Obama administration of deliberately leaving the issue in doubt until after the 2012 election, out of fear that confirming it's mandatory could weaken support for Democratic candidates in jurisdictions with large immigrant populations.

"The word I would use is 'duplicitous,'" said Jessica Vaughan, policy director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which supports tighter controls on immigration, including the Secure Communities program. "They are telling people what they want to hear, not what they mean."

ICE tries to set the record straight It's understandable that local governments would think they could opt out: ICE has indicated in numerous documents distributed to local officials that Secure Communities cannot "activate" or "deploy" in a jurisdiction without their explicit consent.

That begins with the program's 11-page document outlining standard operating procedures, which state that it's subject to "adoption by participating county and local law enforcement agencies" and which "requests" the cooperation of local law enforcement authorities — instead of telling them what to do.

Then, in January 2009 — as the new Democratic administration of Barack Obama was taking office — David J. Venturella, executive director of Secure Communities, said in a (PDF) to the FBI accompanying a memorandum of understanding with California officials that participation in the program "requires a signed statement of intent" at the county and local level.

By this summer, as the program expanded to encompass hundreds of jurisdictions along the Mexican border — including most of Texas, California and Arizona — immigration activists began raising more questions about Secure Communities. In August, ICE responded with a talking-points memo titled (PDF).

One "false claim" addressed in the memo, dated Aug. 17, is that there was "widespread confusion about how jurisdictions can choose not to participate."

The truth, the memo said, is that local officials can request a meeting where both sides can "discuss any issues" and "come to a resolution, which may include ... removing the jurisdiction from the deployment plan."

But local officials who object to Secure Communities said ICE has never honored those promises.

In August, Miguel Márquez, legal counsel for Santa Clara County, Calif., (PDF) highlighting the requirement for adoption by local agencies in the standard operating procedures, which he said "appear to describe Secure Communities as a program that is voluntary for counties."

But "nothing in the standard operating procedures explains ... what the mechanism for 'adoption' is, or whether they can opt out instead if they so choose," Márquez wrote.

As to the local "statement of intent" in Venturella's January 2009 letter, Márquez reported that he had been "unable to find any further information" and that "no department in Santa Clara County has been asked to sign one."

That scenario sounded familiar to Eileen Hirst, chief of staff for San Francisco Sheriff Michael Hennessey, who has also sought to opt out of Secure Communities because it appears to conflict with San Francisco's 20-year status as a "sanctuary city" for immigrants.

Hirst said her department has never been asked to sign anything approving Secure Communities. In fact, at a meeting with state and federal officials in April, ICE representatives said there were no documents to sign at all, Hirst said.

And Tejada, of Arlington County, Va., said his board waited until after ICE issued its August memo to take a vote on opting out. It was still turned down.

"'Setting the Record Straight,'" he said, laughing. "What a name!"

What are 'next appropriate steps'?

Other local government and police leaders said they, too, have tried to decline to participate in the program but have been rebuffed. They said they were told that ICE is happy to discuss their concerns and that it could consider delaying the date their jurisdiction is "activated."

But, they said, ICE's responses never address their actual request: Can we opt out of the program itself?

When an msnbc.com reporter asked numerous ICE officials that question, they wouldn't answer. And they said they couldn't discuss why they couldn't comment.

In a two-paragraph statement this week in response to detailed written questions, Brian P. Hale, ICE's director of public affairs, wrote that "ICE independently enforces the immigration law as appropriate" and "seeks to work with local law enforcement agencies to address any concerns and determine next appropriate steps."

He did not say what those steps might include, and ICE said it couldn't elaborate.

That's essentially the same answer Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., chairwoman of the Judiciary subcommittee on immigration and border security, got when she fired off a letter in July asking for "a clear explanation of how local law enforcement agencies may opt out of Secure Communities by having the fingerprints they collect and submit ... checked against criminal, but not immigration, databases."

(PDF) six weeks later didn't answer Lofgren's question. Instead, it repeated ICE's mantra that local authorities should notify ICE if they don't want to "participate in the Secure Communities deployment plan," without saying whether they could actually be allowed to opt out.

Top priority: 'Identify and process all criminal aliens'

It seems, in fact, that ICE never meant for local authorities to have a say.

Dozens of Secure Communities technical documents and other ICE communications make it clear that the program is intended to eventually review the immigration status of every person arrested in the United States.

In its original organizing documents and in quarterly reports to congressional committees, ICE declares that the first priority for Secure Communities is to "identify and process all criminal aliens subject to removal while in federal, state and local custody."

In its field training manual, ICE tells agents that "Secure Communities is committed to improving public safety by identifying, detaining and removing all criminal aliens held in custody and at large."

And: "Secure Communities will expand the capability to screen for criminal aliens to all local jails and booking stations electronically as individuals are brought into custody."

Local officials can disapprove all they want. The idea, ICE said in a (PDF) in May, is to create "a virtual ICE presence at jails and booking locations in jurisdictions across the country."

That hasn't stopped communities from trying to break free anyway.

In California, the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously late last month to send formal notice asking ICE to stop using fingerprints collected in the county, even if it turns out the request has no official effect.

Board member George Shirakawa acknowledged that the vote was "merely symbolic." But he said it was still important because it "sends a message."

"We are not going to create an atmosphere of fear in our communities," he declared.

|