The residue of hydrothermal vents on the flanks of a volcano on Mars could be signs of one of the most recent habitable environments on the Red Planet, researchers suggest.

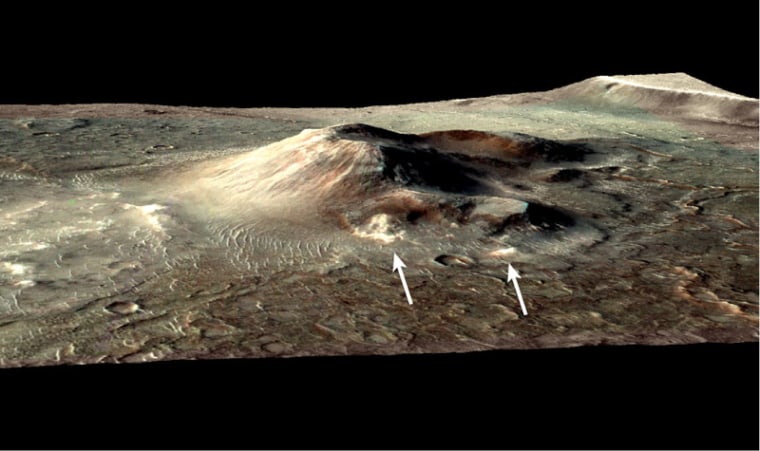

Scientists investigated data gathered on the Martian volcanoes in the Syrtis Major region of the Red Planet using a powerful spectrometer on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. They focused specifically on deposits near the relatively young Nili Patera volcanic cone, which date back some 3.7 billion years to the Early Hesperian epoch, the beginning of the middle era of Mars' history. [ Photo of the Martian volcano vents ]

When hot water flows through rock, it dissolves minerals, enriching the water with silica, or silicon oxide. When this water cools off and is exposed to air, a material called hydrated silica crystallizes, which is what the investigators unexpectedly detected in the deposits near Nili Patera.

The discovery suggests that the vents once served as tiny habitable pockets on Mars where primitive forms of life on Mars, if any existed, could have found refuge.

"When you have water and heat, as you have at this site, you have the opportunity for habitability a place where conditions for life, if it was there, could have been supported," study co-author John Mustard, a geology professor at Brown University at Providence, R.I., told Space.com.

The fan shape of the deposits and their location in and around a volcanic cone also suggest they came from a hydrothermal system, he added.

"If you go to Hawaii or Iceland and you walk among the volcanic cones, you can see steaming vents and hydrated silica around them," Mustard said.

On Earth, scientists think hydrothermal environments with silica deposits have significant potential for preserving microbial fossils.

In the future, the researchers hope to better understand how habitable this site might have been how hot or acidic it was, for instance.

"We could also explore analogous environments on Earth, such as fumaroles on Hawaii or places in Iceland — see if we can detect similar sets of chemical signatures from orbit and see what kind of biological communities are associated with them," Mustard said.

The study was headed up by lead author John Skok at Brown University. Along with Mustard, Skok and the pairs colleagues detailed their findings online Oct. 31 in the journal Nature Geosciences.