Hundreds looked on as an angry mob dragged a black University of Missouri janitor from his jail cell in April 1923, publicly lynching him before he could stand trial on charges of raping a white professor's 14-year-old daughter.

Historians say the instigators included some of Columbia's most prominent citizens. The crowd that watched James T. Scott hang was filled with laughing and cheering students from the first public university west of the Mississippi River.

Eighty-seven years later, civic leaders have come together to confront an ugly episode in Columbia and correct the record on the death of Scott, who insisted the rape allegation was a case of mistaken identity.

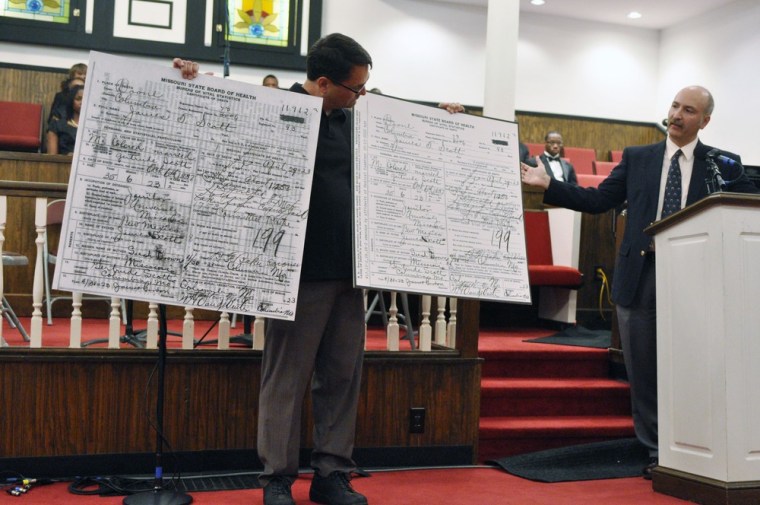

Local filmmaker Scott Wilson teamed up last month with the Boone County medical examiner's office to successfully lobby state officials to change the cause of death on Scott's death certificate.

The primary cause is now listed as "asphyxia due to hanging by lynching by assailants." A secondary cause of "committed rape" was removed and now reads "never tried or convicted of rape."

"This was done solely for one purpose," Dr. Michael Panella, associate medical examiner, said of the original listing. "And that was to justify an unjustifiable and heinous act."

Scott, a 35-year-old married janitor at the medical school, was arrested April 21, 1923, one day after the reported rape of Regina Almstedt, the teenage daughter of a German literature professor.

The girl identified Scott based on his distinctive "Charlie Chaplin" mustache and a chemical odor she said her attacker carried. Scott maintained his innocence to the very end. With the noose at the ready, he spoke of his own 15-year-old daughter. He also identified a cellmate whom he said confessed to the attack.

Even the girl's father implored the 1,000-man mob to spare Scott until he could stand trial. Hermann Almstedt was reportedly threatened with a lynching of his own. Scott was killed eight days after his arrest.

Several hundred people gathered Sunday at Second Missionary Baptist Church for a service organized to raise money for a headstone for Scott's grave. A nondescript grave marker now designates his burial site in what was once the segregated section of the 190-year-old Columbia cemetery.

Organizers say the effort is about trying heal wounds from a decidedly dark chapter in local history.

Keynote speaker Patrick Huber, an associate professor of history at Missouri University of Science and Technology whose undergraduate thesis discussed the Scott lynching, said the killing was one of more than 4,000 racially motivated lynchings in this country from 1885 to 1923 — including 75 in Missouri.

Communities nationwide are working to re-examine histories of racist violent acts, said Mark Potok, who tracks hate crimes for the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala. Among those places is Tulsa, Okla., which recently opened a "reconciliation park" recognizing a deadly 1921 riot that killed dozens, injured hundreds and destroyed thousands of homes.

"There are more and more places around America trying to come to grips with their racial past," he said.

Minneapolis resident Bradley Stewart was among those at the downtown Columbia church Sunday night. His sister Janna, a southern Missouri lawyer, described how their late father talked about attending Scott's lynching as a 4-year-old.

Stewart said he came to the service "to bury family ghosts."

Columbia mayor and longtime resident Bob McDavid said he only recently learned about Scott, but told those gathered that an event recent enough to occur in the their lifetime was one that never should be forgotten.

"The James Scott lynching did not happen in a different world, in a different time or a different place," he said.