“Now, you're thinking of Europe as Germany and France. I don't. I think that's old Europe. If you look at the entire NATO Europe today, the center of gravity is shifting to the East. And there are a lot of new members. And if you just take the list of all the members of NATO and all of those who have been invited in recently -- what is it? Twenty-six, something like that? You're right. Germany has been a problem, and France has been a problem.”

-- Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, speaking about Iraq with foreign journalists, Jan. 22, 2003

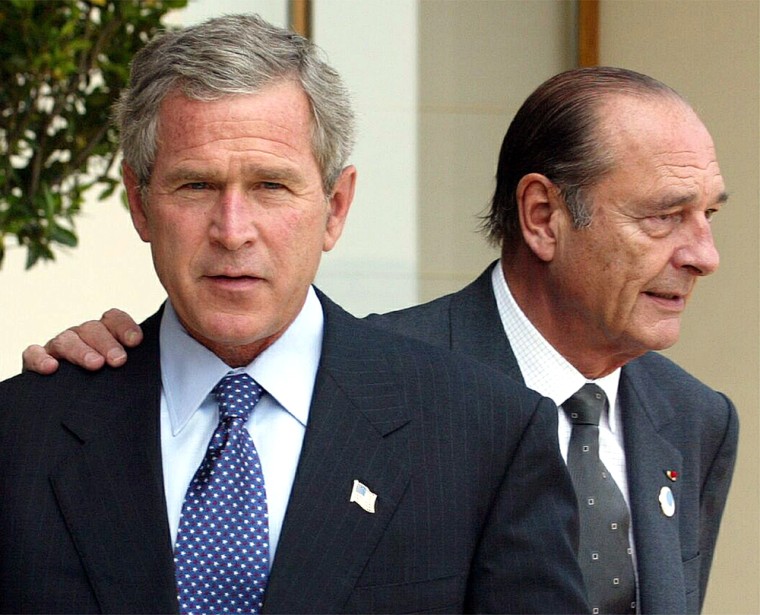

PARIS — Even in full context and with the benefit of a year’s time passed, Rumsfeld’s assertion that European opposition to the Iraq war came only from “old Europe” is startling. His remarks came to be viewed as the nadir of trans-Atlantic relations, and while both sides say they are ready to move on, the damage to the alliance between the world’s most powerful democratic states persists to this day. The rift not only divides Washington from old allies in Paris and Berlin, but also Europeans from each other and senior Bush administration officials among themselves.

What was it about Rumsfeld’s words that day that so angered so many Europeans? Was the outrage calculated or blown out of proportion? Or did his characterization all too clearly define the sclerosis afflicting the half century old Atlantic alliance? Is this rift a passing storm, or a more permanent feature of the post-9/11 political landscape?

In a five-part series beginning today, MSNBC.com will examine the state of the trans-Atlantic relationship a year after Rumsfeld dismissed France and Germany as passé. In stories reported from Paris, Berlin, London, Washington and Warsaw, the series will take the temperature and gauge the health and future prospects of the Western alliance, all based on discussions with senior officials, academics and average citizens on both continents.

Two continents, many views

It is tempting to simplify the rift as one between Americans and Europeans, between the superpower and the mid-sized powers. In this view, as the American political scientist Robert Kagan memorably put it, "Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus." In the wake of the Iraq war, this looks far too general. The decision to go to war without U.N. sanction and without more evidence of the threat posed by Iraq caused significant discomfort in America, too. Similarly, many European governments joined the American-led campaign despite polls suggesting deep opposition among their populations. Such major Euro-players as Britain, Denmark, Spain and Poland endorsed the American argument and sent their soldiers to fight and die beside them.

There were European voices, too, who took issue with the strident, vocal attacks being made on U.S. and British motives.

“I believe that German and French behavior, and especially language, were inexcusable,” wrote Otto Graf Lambsdorff, a senior German statesman and former minister, in an influential Op-Ed in the International Herald-Tribune. “For a major ally of the United States to announce in advance that it would not abide by any United Nations resolution asking for military action was to drive an unprecedented political wedge among us.”

Lambsdorff is not in the majority on this question, either in Germany or on the larger European scene. To many Europeans, Rumsfeld’s words – and more importantly, the condescending tone many Europeans say they detected throughout the pre-war debate last year -- appear to be far more than casual jousting with reporters. His reference to the new democracies of eastern Europe, in particular, raised long suppressed suspicions that the United States has begun to view its old friends, and especially their ambitious plan to unite a continent under the European Union’s banner, as more of a threat to America than a partnership with it.

With many of those eastern and central European nations supporting the U.S. position, there was a sense that Rumsfeld had let slip a nefarious U.S. plot to drive a wedge between EU nations and halt the effort to create a second great democratic center of power right in its tracks.

“What they see from here is that the United States has changed its view of the European Union, which was created, after all, to make sure the U.S. never again has to come over here and ‘save Europe from itself'," says Dr. Jens van Scherpenberg, the head of the Americas project at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. “The Iraq debate was the first time it became clear to Europeans that America, or at least this American administration, wants Europe to remain weak and to keep quiet. That was a terrible, terrible shock.”

A break or a passing storm?

Oddly, Rumsfeld’s characterization of Europe that day appeared to have struck the reporters in the briefing room as just another instance of Rumsfeld’s feisty banter. Indeed, the very next question came from a reporter from the BBC, the British broadcaster whose critical reports on the Iraq debate pulled no punches, and whose questioning of the war’s motives would come to threaten Prime Minister Tony Blair’s hold on power. Yet that day one year ago, the BBC correspondent failed to grasp the significance of Rumsfeld’s quip. He asked, instead, about United Nations weapons inspectors. It was only the next day, when the French and German foreign ministries digested Rumsfeld’s remarks, that the trans-Atlantic relationship truly hit rock bottom.

From that day on, the debate between Washington and London, on the one hand, and Paris and Berlin, on the other, took on a darker quality, degenerating at one point to outright name calling. Paul Wolfowitz, deputy U.S. defense secretary, cited the failure to stand up to Hitler in the 1930s and suggested French and German concerns about Iraq simply masked their preference to appease dictators. A German minister went Wolfowitz one better, comparing George W. Bush’s foreign policy to Hitler's.

Even since the toppling of Saddam, both sides appear as keen to justify their position as with healing their breach. The French and Germans continue to emphasize the fact that no weapons of mass destruction have been found, and America' s administration responds that, but for its determination, Saddam Hussein would still be in power.

With the war’s major action over and Saddam in captivity, a joint determination to help stabilize Iraq may be congealing. But does this portend a full healing of the wounds that the Iraq debate opened, or merely a grudging, cold-eyed decision not to let last year’s principles stand in the way of national economic and political interests?

Coming Monday, Jan. 26: Germany -- burdened by history, or motivated by it?