Humans have long depended on machines to explore strange, new worlds — guiding mechanical rovers from millions of miles away, then waiting and hoping that the robotic beast carried out its instructions.

Spirit and Opportunity, NASA's twin Mars Exploration Rovers, are no exception to the rule. But while their onboard computers are based on past spacecraft computing systems, engineers have beefed up their memory capacities to handle what is hoped to be a slew of data from Mars despite a serious glitch with the rover, Spirit.

"These computers are absolutely identical, and what's more impressive is that there is just one for each rover," said Victor Scuderi, manager of space products for Information and Electronics Warfare Systems, or IEWS, in Manassas, Va. IEWS, part of BAE Systems, provided the computer at the heart of the rovers. "It's quite unusual to have a single computer for the whole mission," Scuderi said, adding that many missions tend to have redundant systems as a guard against failure.

But the rovers' computers are based on systems that have been proven repeatedly in the past and present, particularly in the 1997 Mars Pathfinder mission and the ongoing Mars Odyssey, which has led to some faith in the technology on NASA's part.

A standard Martian brain

Both the hardware and operating software onboard Spirit and Opportunity are similar to those used in the highly successful Pathfinder mission, which dropped a lander and the small Sojourner rover onto Red Planet.

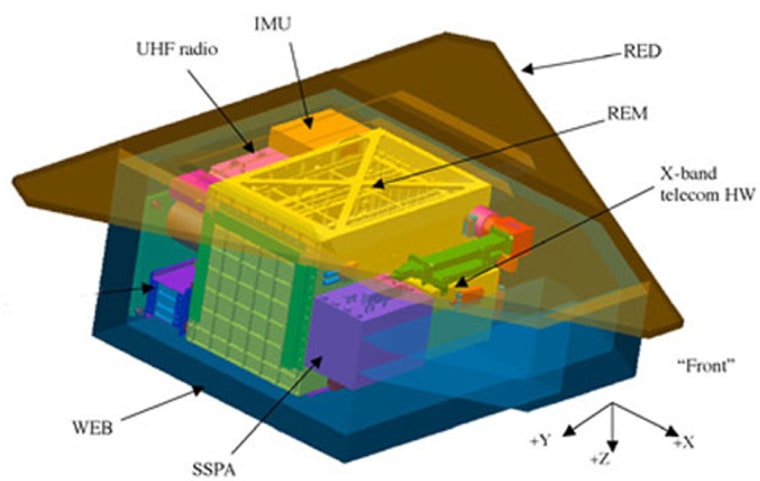

At the nerve center of each Mars Exploration Rover is a 6-by-9-inch (15-by-23-centimeter) electronics board containing one computer responsible for every process that goes into a mission, whether it be monitoring spacecraft health in transit, deploying parachutes during landing, or roving about the Red Planet. The computer, called a RAD6000, is a tried and true component for NASA space missions that has formed the brains of past Mars missions as well as the recent Stardust comet encounter.

"This has become a real workhorse for space missions," Scuderi said. "We currently have about 150 of these [computers] in space today."

RAD6000 microprocessors are radiation-hardened versions of the PowerPC chips that powered Macintosh computers in the early 1990s, containing 128 megabytes of random access memory and capable of carrying out about 20 million instructions per second. A critical feature of the spaceworthy chips — developed jointly by BAE Systems, JPL and the Air Force Research Laboratory — is the radiation shielding, which uses a series of resistors and capacitors to ground harmful radiation before it can damage onboard electronics.

"In space, there are tons of high-energy particles, X-rays, gamma rays, you name it," Scuderi told Space.com. "If [a computer] is not protected against them, they could create short circuits, create fake bits or burn up electronics."

Because today's Mars rovers are much larger than Sojourner, with missions planned to last almost three times as long, JPL engineers added another 256 megabytes of flash memory — the same type used to store pictures in digital cameras — to hold more mission data. Altogether, each Mars Exploration Rover has more than 1,000 times the memory capacity of Sojourner.

The operating systems running on Spirit and Opportunity are based on a flexible commercial platform initially chosen by JPL engineers for its reliability.

"[JPL] needed the tools to be able to develop their mission software on a system from someone with a proven track record," explained Steven Blackman, director of business development for aerospace and defense for the software company Wind River. The Alameda, Calif.-based company developed the VxWorks real-time operating system used aboard the Mars rovers as well as in other NASA and European Space Agency missions.

In addition to VxWorks' reliability, the system allows users to add software patches — such as a glitch fix or upgrade — without interruption while a mission is in flight. "We’ve always had that [feature] so you don't have to shut down, reload and restart after every patch," Blackman said, adding that some commercial desktop systems require users to reboot their computers after a patch.

Keeping warm and in touch

Rover computers, as well as other equipment aboard Spirit and Opportunity, can operate properly only within a set temperature range, which stretches from -40 degrees Fahrenheit (-40 degrees Celsius) at the low end on up to 104 degrees F (40 degrees C) at the high.

While a hot day on Mars is nothing for the robot brains to worry over — they tend to top out at 71 degrees F (22 degrees C) — nighttime is another matter. Once the sun sets on Mars, the temperature can drop down to -140 degrees Fahrenheit (-100 degrees C).

To survive the frigid Martian night, the rovers' computers are housed in warm electronics boxes, heated by a combination of electric heaters, eight radioisotope heater units and the natural warmth from the electronics themselves.

Each rover computer is programmed to periodically takes its own temperature and check its ability to communicate with Earth to verify that all systems are in working order and that the rover is "healthy." The computer also is responsible for rover navigation, and constantly uses images from an array of hazard and navigation cameras, as well as standing movement orders from mission controllers, to keep itself moving smoothly in the right direction.

A quirky Spirit

The current Mars rovers may rely on proven computer technology, but for Spirit the journey has not been glitch-free.

After a promising start to its mission, the Spirit rover — the first of the twins to land on Mars — stopped sending proper data to JPL scientists 18 days into the mission and later baffled ground controllers by rebooting itself over and over again. Since then, mission controllers have been able to regain reliable communications with the rover and continue to study what may have caused the malfunction.

Recent reports cite the breakdown of software that controls file management in Spirit's computer memory as the leading theory to the rover's computer woes. While JPL scientists have expressed confidence they can overcome the problem, possibly in a matter of weeks, the hardware and software manufactures behind the computer system are more than ready to help.

"If they ask, we come," Blackman said, echoing the enthusiasm of BAE officials. "I think when something like this happens, the whole community responds to it."