Scientists say they have created a new form of matter and predict it could help lead to the next generation of superconductors for use in power distribution, more efficient trains and countless other applications.

The new matter form is called a fermionic condensate, and it is the sixth known form of matter — after gases, solids, liquids, plasma and Bose-Einstein condensate, created only in 1995.

“What we’ve done is create this new exotic form of matter,” said Deborah Jin, a physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s joint lab with the University of Colorado, who led the study.

“It is a scientific breakthrough in providing a new type of quantum mechanical behavior,” Jin added during a news conference.

A superconductor, sort of

The cloud of supercooled potassium atoms brings Jin and fellow researchers one step closer to an everyday, usable superconductor — a material that conducts electricity without losing any of its energy.

“It is related to a Bose-Einstein condensate,” Jin said. ”It’s not a superconductor, but it is really something in between these two that may help us in science link these two interesting behaviors.”

And other researchers may find practical applications.

“If you had a superconductor, you could transmit electricity with no losses,” Jin said. “Right now something like 10 percent of all electricity we produce in the United States is lost. It heats up wires. It doesn’t do anybody any good.”

Superconductors also could allow for the invention of magnetically levitated trains, she added. Free of friction, they could glide along at high speeds using a fraction of the energy trains now use.

Better than a boson

Jin, a recent recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” was building on the discovery of the Bose-Einstein condensate by her colleagues Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman. They won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery.

Bose-Einstein condensates are collections of thousands of ultracold particles that occupy a single quantum state. They all essentially behave like a single, huge superatom. But Jin said these Bose-Einstein condensates are made with bosons, which like to act in unison.

“Bosons are copycats. They basically want to do what everyone else is doing,” she said.

Her team’s new form of matter uses fermions — the everyday building blocks of matter that include protons, electrons and neutrons.

“They are not copycats,” Jin said. “Fermions are your independent thinkers — they don’t copy their neighbors.”

Jin’s team coaxed them into doing just that.

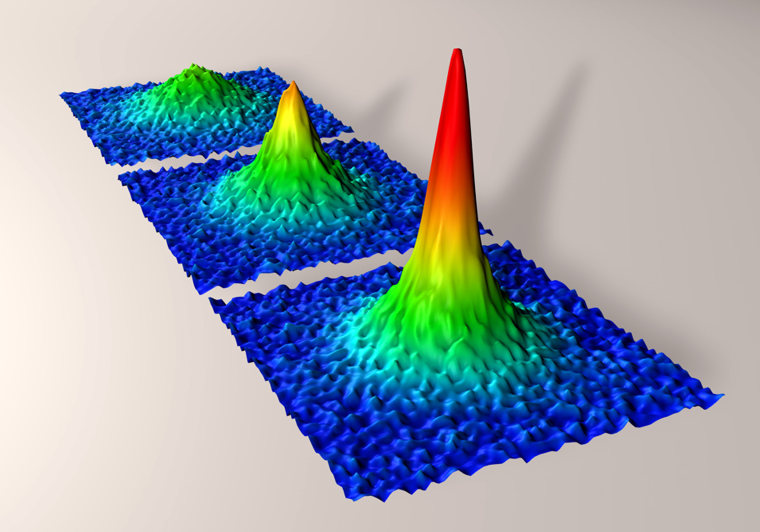

They cooled potassium gas to a billionth of a degree above absolute zero, or minus-459 degrees Fahrenheit — which is the point at which matter stops moving. They confined that supercooled gas in a vacuum chamber, then used magnetic fields and laser light to manipulate the potassium atoms into pairing up.

“This is very similar to what happens to electrons in a superconductor,” Jin said.

Practical application

This is more likely to provide applications in the practical world than a Bose-Einstein condensate, she said, because fermions are what make up solid matter.

Bosons, in contrast, are seen in photons, and subatomic particles called W and Z particles.

Jin stressed that her team worked with a supercooled gas, which provides little opportunity for everyday application. But the way the potassium atoms acted suggested there should be a way to translate the behavior into a room-temperature solid.

“Our atoms are more strongly attracted to one another than in normal superconductors,” she said.