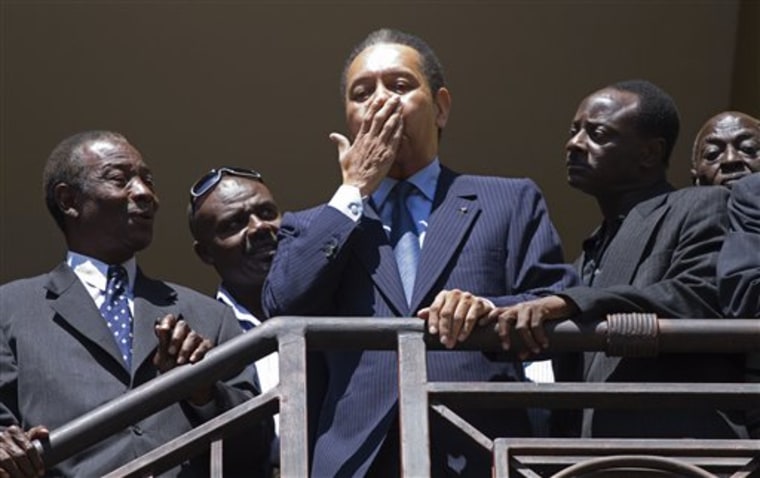

Former dictator Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier slipped out the back of his hotel Thursday and was driven to a private home on a mountain above Haiti's capital, in the latest unexpected twist in his surprise return to the country that kicked him out nearly 25 years ago.

Duvalier, who faces a court investigation in Haiti, had a plane ticket to leave the country in the morning along with his entourage. But as the day wore on it became clear the ex-"president for life," who is 59 and showing signs of ailing health, wasn't going anywhere.

The reasons for his prolonged stay remain as murky as his motivation for coming back in the first place, but advisers and confidants cite two primary motivations: the lack of a valid passport and the ongoing court investigation against him on allegations of corruption and human-rights abuses from his reign.

As his scheduled flight took off he was still in the international-style hotel in Petionville, where he had stayed in a standard room. After a group lunch on its covered patio restaurant his girlfriend, Veronique Roy, walked to a waiting car at the hotel's main door to draw off most of the press while he was shepherded to a separate car behind the compound on a concrete loading dock.

He ended up in a private home.

The court cases followed too, with investigating Judge Carves Jean and Haiti's chief prosecutor, Auguste Aristidas, among his first visitors there, Radio Metropole reported.

Defense attorney Reynold Georges told reporters earlier in the day that he couldn't speculate how long the ex-dictator would stay in Haiti, but that it would take at least two weeks to resolve the legal cases filed against him.

"He will have to answer that question himself but for now, we're here," Georges said.

Asked if Duvalier had been invited to Haiti by anyone in the government, the attorney said not to his knowledge. "It's his country. He doesn't need an invitation."

Duvalier assumed power in 1971 at age 19 on the death of his notorious father, Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier. They presided over one of the darkest chapters in Haitian history, a period when a secret police force known as the Tonton Macoute tortured and killed opponents.

The private militia of sunglass-wearing thugs enforced the dynasty's absolute power and lived off extortion. On Thursday, men identifying themselves as former Macoutes milled outside the lobby as other Duvalier associates shuttled back and forth from his third-floor room. Roy greeted the former militia men with hugs.

Aristide wants to come homeDuvalier's move came a day after ousted former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide sent out a letter saying he is ready to come back from six years of South African exile "today, tomorrow, at any time."

"As far as I am concerned, I am ready," he wrote in an e-mail distributed by supporters and posted online. "The purpose is very clear: To contribute to serving my Haitian sisters and brothers as a simple citizen in the field of education."

Aristide was ousted in 2004, leaving Haiti aboard a U.S. plane as a small group of rebels neared the capital. His return has been a principal demand of his Fanmi Lavalas party, which has lost influence as electoral officials blocked it from participating in elections including the disputed Nov. 28 vote now under challenge — though Aristide himself has remained a widely popular figure.

His Haitian passport has expired, his aides said, but Aristide said he hoped an agreement by Haitian and South African authorities could permit his return.

A firebrand former Roman Catholic priest, ousted by a 2004 rebellion involving former soldiers, Aristide remains wildly popular in his homeland.

He is two years younger than Duvalier, who he spoke against as a Roman Catholic priest in the La Saline slum.

Together the men represent the two main oppositional forces in Haitian politics over the last half century: Stable, often brutal authoritarianism in favor of elites against charismatic populism that opponents said bordered on demagoguery.

According to Duvalier's confidants, the two men have never met. Their mutual presence in Haiti could cause long-simmering tensions to erupt.

Aristide did not endorse a candidate in the current race and has said he would not seek office if he came back.

Instead he said in the letter, whose authenticity was confirmed by Lavalas spokeswoman Maryse Narcisse, his return was necessary to help his countrymen and for his medical needs following six eye surgeries in his six years of exile.

"The unbearable pain experienced in the winter must be avoided in order to reduce any risk of further complications and blindness," he said. South African winter begins in June.

"Let us hope that the Haitian and South African governments will enter into communication in order to make that happen in the next coming days," he said.

U.S. Twitter responseThe U.S. State Department reacted to the letter in a series of posts by spokesman P.J. Crowley on Twitter.

"This is an important period for Haiti. What it needs is calm, not divisive actions that distract from the task of forming a new government," said one.

The other: "We do not doubt President Aristide's desire to help the people of Haiti. But today Haiti needs to focus on its future, not its past."

Duvalier also applied for a new passport Wednesday and intends to leave the country when he gets it, a spokesman said, insisting that the once-reviled strongman can neither be forced to leave his homeland or compelled to stay and face a potential criminal trial on allegations of corruption and human-rights abuses.