When Japan lost a large chunk of its electricity-generating capacity to the one-two punch of earthquake and tsunami, the narrative in parts of one of the world’s most technologically advanced societies was transformed overnight into one of Third World hardship.

For most Japanese, the rolling outages instituted in the wake of the twin disasters translate to inconvenience, sacrifice and economic loss. But for tens of thousands who are now homeless and huddled in evacuation centers in the hard-hit northeast, the stakes are much higher.

"In known evacuation centers, people who reached actual evacuation centers, you have a half million Japanese displaced. They don't have water, they don't have electricity, they don't have oil," said Sheila Smith, senior fellow for Japan Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. "And the temperatures are... dipping below freezing because it's snowing in most of those regions. So there's an acute humanitarian crisis today in Japan.”

Nuclear plant occupies engineers

The difficulties don’t end there. Engineers with the Tokyo Electric Power Co., who normally might be working to get shut-down nuclear plants back online, are instead occupied with a meltdown at the company’s Fukushima Dai-ichi plant.

And for the aid organizations who seek to help the displaced, the lack of power in the quake zone and freezing temperatures are one more reason to rush, and one more challenge to face.

The disaster that struck Japan on Friday knocked out about one-fifth of the country’s 55 nuclear reactors, which normally provide nearly 30 percent of the total power in the country. It also clobbered many thermal plants and knocked out an unknown portion of Japan’s electricity transmission system.

In the northern part of the country, in addition to powerless evacuation centers, the Japanese government said Monday that some 1.25 million homes were without heat, and nearly 3.2 million people were facing reduced gas supplies in the coming days. Other estimates put the number of homes already without power two to three times higher.

In the city of Ishinomaki, previously home to about 164,000 people, Britain's Guardian newspaper reported Monday that survivors seeking heat and shelter crowded into a Red Cross hospital, which was one of the only buildings in the city that still had power.

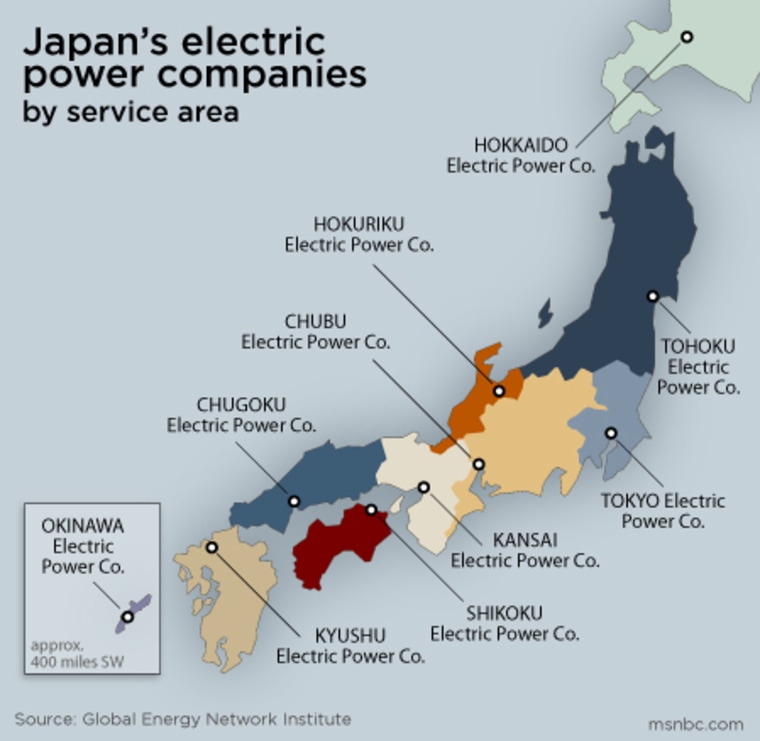

In addition to those with no electricity, customers in many parts of the country are having to cope with three-hour rolling blackouts instituted Monday by TEPCO, the largest power company of 10 in the country and the operator of the Fukushima plants. It said Monday that the rolling blackouts would affect 3 million customers, including large factories and buildings, and would likely continue through the end of April.

On Tuesday a second utility, Tohuku Electric Power Co. said it would also implement electricity rationing, Kyodo News Service reported. Tohuku covers a large swath of the country north of Tokyo, including many of the areas hardest hit by the tsunami.

Tohoku Electric officials said power rationing could run for several months — with outages of up to six hours a day in some prefectures, Kyodo reported, while the company worked to restore quake-damages thermal plants. Company officials said, however, that the rolling blackouts would exclude quake hit areas that are trying to recover.

“What’s probably going on in Japan is they are trying to get as much power as they can to as many people as they can," said Walt Pollock, a retired vice president of power supply for Portland General Electric Co. "So they implement the rolling blackouts … to spread the pain.”

Replacing lost generating capacity suffered in the quake is a long-term problem — especially in the nuclear sector, where seriously damaged plants are unlikely to be repaired or restarted, he said.

"There's no easy answers to how Japan would get ... the kind power that 5 (to) 8 nuclear power plants provide," said Pollock. "The number of nuclear plants they have off line is far greater than the generating capacity of the Grand Coulee Dam, the largest single power generating plant in the (U.S.) Northwest."

There is not much information yet to predict how long it might take to restore some power to sections of Japan that were taken off line by the disaster.

“There are no completely isolated parts of the grid,” said Michael Levi, senior fellow for Energy and the Environment at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Japan has greater interconnection throughout the country than, let's say, in the United States."

"The big open question is, what impact has the physical destruction had on the grid itself" he adds. "So even if in theory you can wheel power from one part to another, if some of the transmission lines are down... that can make that task much more difficult."

Technology fades to black

The Japanese government has called on citizens and businesses to conserve wherever possible to ease the strain on the system. Train system service is limited, stores have shortened hours, escalators and elevators run sporadically, and massive video screens that normally add to the cacophony of Tokyo life were dark.

The rationing is causing discomfort and confusion in many places, as well as logistical problems, which affect aid workers along with residents in a country that is accustomed to modern efficiency.

World Vision International, a Christian nonprofit based in Federal Way, Wash., said the three-person advance team it dispatched to the battered city of Sendai spent one night in cars and a second in a church while on the way deliver bottled water, blankets and baby supplies and pave the way for a larger-scale relief effort.

There is power in the center of Sendai, said communications and outreach director Mitsuko Sobata, Tokyo-based communications and advocacy officer for the organization. But the organization has little information about the situation in Tome, a small city normally about an hour's drive to the north that World Vision plans to aid at the suggestion of the government in Sendai. She says the Tome’s government has been trying to grapple with thousands of evacuees and virtually impossible to reach by phone.

“It certainly complicates the situation,” said Casey Calamusa, international news officer with World Vision who is working in Tokyo. “So much of what we do nowadays is reliant on technology.”