Gleaning the world view of a would-be president based on campaign promises or votes taken in Congress is more of a sorcerer’s trick than a science. Today, with Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts emerging as the prohibitive favorite to take his party's presidential nomination, efforts to conjure up a “world according to Kerry” are underway at major think tanks, in the foreign ministries of the world’s great powers, and, of course, at Bush campaign headquarters.

History suggests that such efforts are imprecise at best. Pledges made during the heat of political battle often turn out to be incompatible with the world a president inherits. Other times, frankly, they are promises made to be broken.

Franklin Roosevelt, for instance, facing a close race for his third term in 1940, promised Americans that “your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” Off they went in 1941.

Dwight Eisenhower promised during his 1952 presidential campaign that, if elected, “I shall go to Korea” to determine for himself how to bring American troops home from what had become a meat grinder of a war. The war dragged on for another year after his victory.

Richard Nixon, campaigning in 1967, touted a “secret plan” to end the Vietnam War, which did not actually end for America until 1973.

Bill Clinton railed against George Bush’s “coddling” of Chinese dictators in 1992, but ultimately declared those same dictators his “strategic partners” in Asia and even found that some of them were funneling illegal campaign donations to his reelection campaign in 1996.

George W. Bush, of course, famously promised as a candidate to inject “humility” into American foreign policy. This two years before al-Qaida injected two airliners into the World Trade Center towers.

Blank slates win states

In fact, for most candidates, only the outline of foreign policy tendencies can be gleaned from past writings, votes or even current promises. That is because most modern presidents and presidential candidates have little or no experience in international or security affairs. The current president’s father, a former CIA director and United Nations ambassador, was the important exception to the rule in recent decades.

“Most of our recent presidents and presidential candidates have been governors rather than senators,” says Prof. Dick Melanson,* who runs a seminar on foreign policy and public opinion at the National Defense University. “No senator has been elected since JFK in 1960, and the lack of for policy experience has not been viewed by the electorate as a real hindrance. In fact, I suspect that Kerry’s well-documented record will be more a hindrance than a help.”

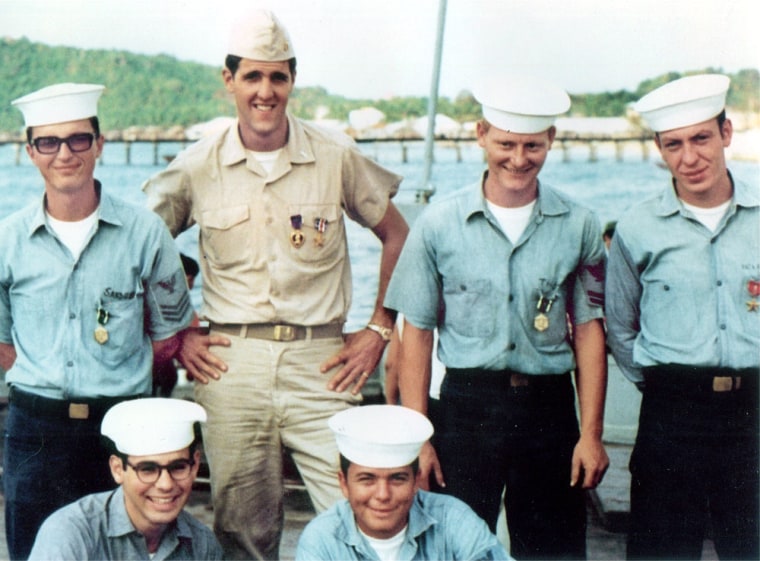

Kerry, indeed, is unusual. A vast flotilla of tea leaves avails itself to those trying to imagine – or to raise fears about - a Kerry foreign policy. As a combat veteran of both fronts of the Vietnam war (the bloody one in Southeast Asia and rhetorical one on the streets and campuses of America), Kerry’s youthful opinions are well known and documented.

Two books, one published last year by noted historian Joel Brinkley ("Tour of Duty"), the other a polemic written by Kerry himself in 1971 ("The New Soldier"), provide ample evidence of his courage under fire and his subsequent determination to oppose the war after leaving the Navy, sometimes employing tactics that may strike today’s voters as irresponsible. The cover of “The New Solder,” for instance, shows Kerry marching with other members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War with an upside down American flag. Kerry has explained that flying the flag upside down is the military signal for “distress,” but unexplained, the photo will strike some Americans as radical, if not downright unpatriotic.

Defensive voting

Still, by virtue of two decades worth of his votes on major foreign policy issues, plus his high profile role as spokesman for Vietnam Veterans Against the War during the early 1970s, Kerry will find himself on the defensive. Sprinkled throughout the nation’s newspaper and video archives are statements and stances that the Bush campaign is bound to harvest.

For instance, Kerry voted in the 1980s against several weapons systems that were workhorses in the Afghan and Iraq wars, including the B-1 bomber, the F-14 and F-15 fighters and the Patriot missile system. Three of the four had serious cost overrun and design problems, which could explain the votes. But the nuance might well be missed in a well-produced Bush television spot.

More seriously, while he supported the current president’s request for the right to use force against Iraq, he voted against the same request by Bush’s father in October of 1991 when Iraqi troops were occupying Kuwait.

“These are votes, no matter how complex the context may have been, that will play very strongly with Bush’s base,” says Melanson. “With Kerry being from the ‘People’s Republic of Massachusetts,’ he already was vulnerable on these kinds of things. The vote against the (1991) Gulf War is just a killer. I honestly just do not know how you explain that.”

Votes versus instincts

But do those votes say anything about who he would be as president?

“What probably matters more is the kind of leadership he is capable of, and the people he surrounds himself with,” says Melanson. “His medals are testimony to the former. We don’t know too much about his team yet.”

One indication of his leanings was his hiring last May of Rand Beers, formerly the chief anti-terrorist official on Bush’s National Security Council. Beers resigned in protest when he felt that American resources that had been hunting for Osama bin Laden and his followers were being diverted toward Iraq.

Beyond Beers and his own Senate staffers, Kerry has said publicly he would seek to appoint veteran foreign policy figures, including Republicans like Brent Scowcroft and James Baker, to senior posts in his administration.

“What he’s trying to do is speak to the Republicans who are uncomfortable with the very ideological foreign policy that the current administration is pursuing,” says Rachel Bronson, an Iraq expert at the Council on Foreign Relations. “And it emphasizes that he has known these people for years, along with his other colleagues on the Senate Foreign Relations committee.”

Patience and virtues

Kerry's Vietnam experience is front and center in his campaign. But his more recent thinking is probably better reflected in two lesser known books written by Kerry, 1997’s “The New War” and last year’s “A Call to Service.”

The latter is a book of the kind written by virtually all candidates outlining a “vision” and, as such, weighed down by the rationalizations, qualifications and finger-pointing that plague American politics. However, taken with several recent speeches, the 2003 book characterizes Kerry as someone deeply disturbed by the low esteem America is now held in abroad. He objects not so much to the fact that Iraq’s dictator was toppled, he says, but the reckless way it was done.

Having himself voted in favor of giving the president the right to use force in Iraq in 2002, Kerry says he was appalled that Bush did not exercise more patience in assembling an international coalition, along with a plan for U.N. involvement after the fighting ended. He describes as “inept” American efforts to win European support and to ensure that there would be international legitimacy to U.S. actions, something he contends would have prevented the bloody insurgency that rages to this day.

“There was a way through that path, in my judgment, with patience and maturity and a readiness and a willingness to be serious,” he told reporters in December, referring to French and German objections. “I don't think it took a lot of skill or analysis to understand that the politics of their populations at that time were not ready to move. And any president ought to understand the politics of other people's electorates, as you try to define how you get from here to there, which is the art of diplomacy.”

Kerry, in fact, differs most seriously with Bush in his insistence that “collective action” is a better way for America to get its way in the world than unilateral American moves.

"We have to work with the international community to define a global strategy that is inclusive, not exclusive, collective and not imperial,” he says in his standard stump speech.

“I think what is interesting about Kerry’s view is the emphasis on a post-conflict plan,” says Bronson. “He explains his vote for the war the way everyone, even the president, is doing today: that he acted based on the information that intelligence agencies gave him. But his anger about the messy and bloody the post-war situation unfolded reflects his Vietnam experience and the feeling that no one thought it through.”

Shadowy networks

Another consistent refrain is the need to curb Saudi financial support to radical Islam. On the stump, he frequently criticizes the Bush team's focus on Iraq and the lack of attention devoted to Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, two nations treated with relative deference by the Bush team even though one clearly has been lax in its handling of terrorist funding and the other was recently revealed to be most serious source of nuclear proliferation on the planet.

In fact, Kerry’s 1997 book, "The New War," centers on the shadowy network of banking, smuggling and laundering operations that underpin terrorist groups and crime syndicates. As such, this is a book relevant to the current struggle against al-Qaida and its financial benefactors.

Yet Kerry has sometimes made too much of his book’s insight, as when he boasted last year on FOX News that his book foreshadowed the 2001 terrorist strikes.

In reality, most of the book is dedicated to international criminal gangs, not terrorists. While he does rightly predict that “one mega-terrorist event in any of the great cities of the world [will] change the world in a single day," he does not mention Islamic fundamentalism or Osama bin Laden. As Michael Crowley of The New Republic points out, “If the future Kerry predicted really had arrived, we'd currently be locked in a vicious cyber-war with CD-pirating Japanese yakuza, Chinese kidney-traders, and Italian mobsters -- not hunting Islamic fundamentalists potentially armed with weapons of mass destruction.”

Nonetheless, notes Bronson, the fact that he chose to write a book about these international syndicates “indicates he really is a foreign policy guy. This is an issue that many foreign policy experts would have said, at the time, is a bit beside the point. Sept. 11 showed that it was not at all beside the point. He has real depth of knowledge on these things, and he will be able to bring that to debates with Bush.”

*Prof. Melanson stresses that he speaks for himself here, and not for the Department of Defense.