On a wedge of land where criss-crossing canals have killed off native plants and sped erosion, the Army Corps of Engineers has a controversial proposal for undoing environmental damage: They want to dig another canal.

The trench is a key part of a $3 billion plan to fix damage left by the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet, a 78-mile shipping channel dug in the 1960s. The corps says the work will help protect New Orleans from hurricanes by restoring wetlands, the natural buffer Louisiana is losing along this low-lying coast.

Locals, however, are worried.

"The bottom line with the corps: Fix one problem, create four more," said Michael DeFranza, a handyman salvaging debris dumped in a tangle of woods near where the new canal is slated to cross. "They go in with good intentions, but it's poor long-term planning."

Scientists and many residents of St. Bernard Parish agree that its marshes need an infusion of nourishing Mississippi River water and the land-building sediment it carries. But after a century of flooding and environmental damage caused by misguided water projects — many built by federal engineers — the corps is having trouble selling its latest one.

In 1923, the parish and New Orleans' Lower 9th Ward were separated from the city when the Industrial Canal was dug. It was designed to connect the trade corridor along the Mississippi River with industrial sites near Lake Pontchartrain, but turned into a flood maker that inundated both areas during Hurricane Betsy in 1965 and Katrina in 2005.

Four years after the Industrial Canal opened, St. Bernard was intentionally flooded during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 when a section of levee was dynamited to relieve the flood risk to New Orleans. Homes, farms and businesses were washed away.

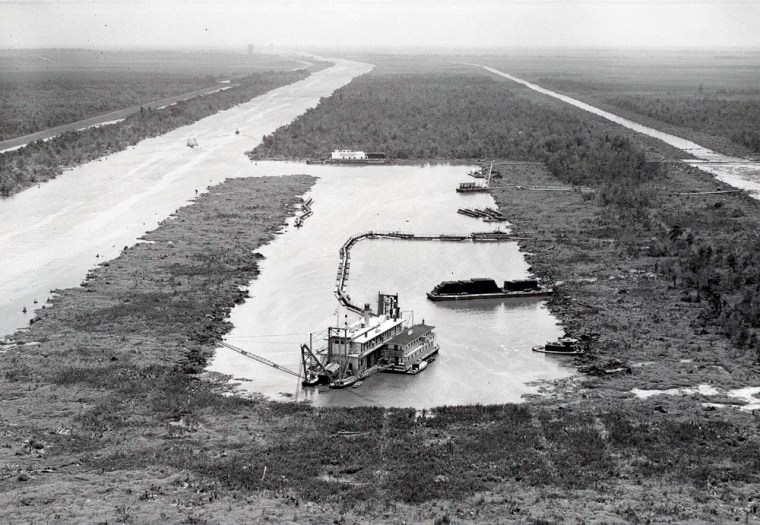

Dozens more large and small canals followed. In the 1930s, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway went in between New Orleans and St. Bernard, chewing up a slice of marsh known as the Golden Triangle.

"You can't just cut the levee and dig these straight, hard lines across this deltaic environment without consequences," said Richard Campanella, a geographer at Tulane University who has studied the history of canal digging in Louisiana, which dates back to 1719.

Worst of all was the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet.

Imagined as a shortcut to New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico for ships, it turned into a fiasco. Salt water washed in and killed cypress forests that had helped hold delta soil in place with their roots; the channel's banks eroded away and took with them large chunks of marsh. Over the next 40 years, the channel destroyed 40 square miles and damaged 1,000 square miles.

By the time Katrina hit, the channel had left St. Bernard's flanks — which also serve as New Orleans' backdoor — bare and exposed.

Katrina's storm surge roared up the channel known to locals as "Mister Go," and destroyed the levees and floodwalls protecting St. Bernard and the Lower 9th Ward. In 2009, a federal judge ruled that the Army Corps' negligence in maintaining the Mister Go caused the flooding.

That record has made it difficult for the corps to convince locals of its plan to fix damage from the Mister Go, even though the agency has in recent years made ecological re-engineering a cornerstone of its mission. In the past decade, the corps' has spent about $500 million a year on saving the ecology of the Everglades in Florida and bringing back wetlands and fish species, such as pallid sturgeon and salmon, along the Missouri, Mississippi and Columbia rivers.

On paper, the proposed canal seems modest and beneficial. It would run about 3 miles over an empty cow pasture in Meraux, channeling water from the Mississippi to ravished and sinking marshes. Scientists agree that something needs to be done — and fast.

"If you don't get aggressive in that area, you will find what we are really concerned about: The Gulf of Mexico lapping up against the levees of New Orleans," said Robert Twilley, a delta scientist at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette.

The corps says the freshwater will "nourish existing marshes" and help rebuild wetlands, make the basins less salty and inject sediment and nutrients into the damaged ecosystem. It's meant to do work that was once accomplished naturally by river tributaries and bayous that have been closed off one by one since the 1880s.

The corps also wants to bolster marshes with mud it would dredge up, plant cypress trees and harden eroding shorelines with rock dikes. The corps says its plan — mandated by Congress in 2007 — will restore roughly 93 square miles of the lost land.

In locals' eyes, the biggest stumbling block is the canal. At recent public meetings, hundreds showed up to denounce it.

"I'm going to say here that in another 20 years we're going to be back to the drawing board and saying, 'Oops,' just like they said with the MRGO — 'oops!'" said Donald Merwin, who works at a machine shop.

Some fear that the canal would be a new source of flooding.

"You don't need more water! We got enough water in this parish already," spewed Mike Fireck, a 40-year-old machinist who works for Merwin.

Fishermen spoke out against the freshwater diversion for other reasons: They don't want to lose the salty waters they've come to enjoy in the wake of the swamps' demise and the speckled trout, red fish and oysters that now thrive there.

Many locals — along with parish leaders and some scientists — favor an alternate proposal: Re-use the nearby Violet Canal instead of digging a new channel. They want the corps to re-engineer the canal by widening it and installing a system of pipes to get freshwater from the river to the back swamps.

The corps has studied the Violet option but says it appears to be too costly because about 100 structures including a bridge, a government building and homes would have to be moved, said Greg Miller, a corps project manager.

"I'm very well aware of the concerns," Miller said.

But he dismissed fears that the new canal would cause flooding. He says that the entrance would shut off with gates and that robust levees would line it.

Engineers hope to submit their final plan to the chief of the corps by the end of the year. It will then go to Congress.

A scientist with a nonprofit restoration group said action is desperately needed, but that he can understand why the corps' proposal has drawn the ire of some locals.

"Money, emotions, the environment, it hits on all those things," said John Lopez, science director for the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation. "I can see where people wouldn't feel comfortable with it — from a historical perspective."

The Lake Pontchartrain basin, which surrounds the area of the restoration project, is falling apart. Since the 1930s, about 600 square miles of land have been lost, a process that has accelerated since Katrina stirred it up.

"Back of there, it used to be all cypress marsh," said Lionel "Da Pope" Alphonso, a 64-year-old bar owner along the Violet Canal known for dressing up as the Pope for New Orleans Saints football games. "Now it's all flat grassland and open water."